Yossi Cohen, the former head of Mossad, sits in an office that feels more like a private museum than a workspace. Floor-to-ceiling windows in his Modiin home look out over a manicured garden, while the interior is cluttered with telescopes, vintage desks, oversized art books, and Persian rugs. The furniture tells the story of a life lived between worlds—between strategy and leisure, secrecy and exposure. Cohen, 64, carries the quiet intensity of someone who has spent decades operating in the shadows, yet there is warmth in his easy laughter, and a boyish sparkle in his eyes when he recalls operations long kept secret.

“I haven’t spoken to Netanyahu in a year and a half. He is responsible for everything that happened on October 7,” Cohen says bluntly, setting the tone of the interview. He speaks without hesitation, a man accustomed to weighing risk, timing, and consequence.

Asked about Israel’s leadership, his answer is direct: “No one will win the Likud alone—that’s my frustration. I proposed uniting the party from the bottom up, but everyone wants to run independently. They’re all taking from the same cake, and in the end it just gets bigger. There’s one bloc—why not unite it? Why not have a single leader for the whole?” Cohen leans back in his chair, tall and commanding, yet relaxed, as if finally letting out truths he has long held.

He does not shy away from personal ambition. Asked if he could unify Israel’s fragmented political blocs, he answers simply: “Yes.” But he is firm about not wanting to serve as a deputy: “I will not be number two to Naftali Bennett or number three to Benny Gantz. I’m not interested in that. I’m not entering politics right now.”

Still, he admits to a simmering sense of duty. “The need to fix Israel burns inside me. My wife once said, ‘Promise me you won’t go into politics.’ Now she says, ‘Swear you will. It’s your fate.’ Someday I will have to help lead this properly. If there was ever a time, this is it. But right now, there are no elections, and any talk of entering politics is premature and misleading.”

The tension with the current political leadership is clear. “I will be a target, probably from every side,” he says matter-of-factly. And timing, Cohen stresses, is everything. He is still under a warning letter from the state inquiry into the submarine affair, which investigates tender manipulation and bribery. “Yes, I expect this will be resolved. I don’t even know what I’m accused of yet—I just received the letter. I believe everything I did was for the sake of Israel,” he says optimistically.

Cohen is candid about the government: “It should end its days. Honestly, Netanyahu only talks to two ministers—Dermer and Deri. Is this government impressive? No.” Asked about Gila Gamliel’s appointment as intelligence minister, he responds with mock incredulity: “Really? Why not me? I spent 42 years in the system. I was chief of staff, intelligence minister, your arm abroad.”

On Netanyahu’s responsibility after October 7: “He should have taken responsibility and set an election date. Responsibility isn’t taken after a crisis—it’s taken at the start of a term. Everything that happened on October 7 is the Prime Minister’s responsibility, along with everyone else in charge.”

Cohen recounts proposing to Netanyahu a plan to temporarily relocate a million Palestinians from Gaza to the Sinai Peninsula, anticipating that without action, Israel would face civilian casualties. The plan was approved, but when Cohen contacted Qatar and Egypt, the Mossad and Prime Minister’s office publicly distanced themselves from the mission, leaving him “aghast” at the misunderstanding.

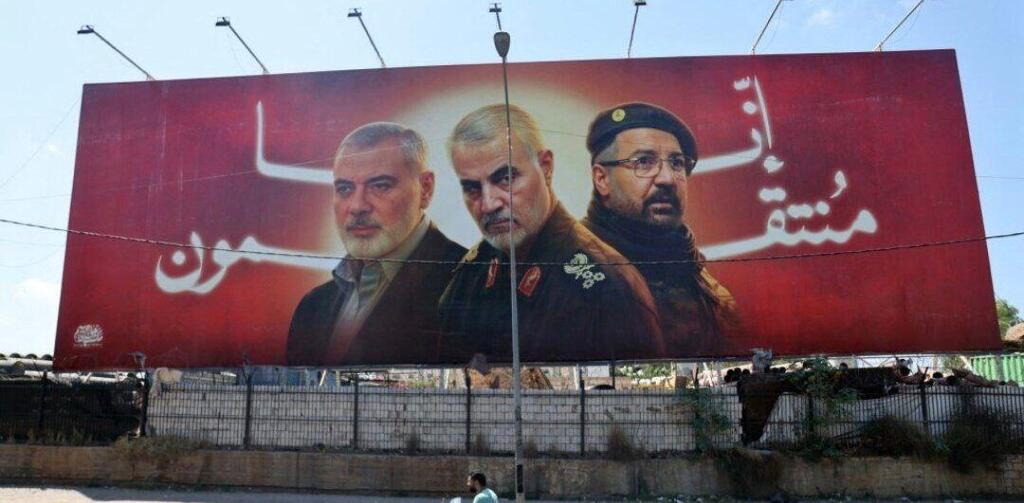

Reflecting on his operational style, Cohen says: “I always wanted to be proactive, identify threats, neutralize them. But the prevailing approach was avoidance—‘Oh, what will happen next?’ For example, I had a full plan to eliminate Qassem Soleimani in Syria. Everything was ready—intelligence, surveillance, logistics—but I was told I couldn’t carry it out because it would spark a war with Iran.”

He is equally frank about Gaza: “After Operation Protective Edge, our intelligence there was insufficient. I suggested Mossad could help, run special operations, enter Gaza—but cooperation was minimal and frustrating. Israel’s approach was avoidance, and that cost lives.”

On the controversial Qatari money transfers: “I reject the claim entirely. I was a messenger, not the instigator. The money didn’t travel with me. We were raising funds for Gaza’s civilians under Shin Bet oversight, with clear accountability for every shekel. This was state policy, not mine or Mossad’s idea. When warned the money could reach the wrong hands, I suggested publicly stopping it. Was it stopped? I leave that question open.”

Cohen also discusses his successes at Mossad. Acquiring Iran’s nuclear archive is a highlight, as is his claim to have invented the “exploding beepers” concept during operations against Hezbollah. “I’m the father of the concept. In 2004, I told then-Mossad chief Meir Dagan I wanted a special operations center that would also handle equipment sales.” He recalls the Natanz explosion: a balance table sold to Iran exploded and destroyed their facility. “How did we get authorized to sell such equipment to Iran? That’s the story.”

He reflects on the character work of intelligence tradecraft: “I played every role—shoe dealer, lawyer, philosopher, businessman, investor’s son, broker, archaeologist. After an operation, you feel like a stage actor leaving the theater, going for a coffee. You inhabit these lives fully.”

Cohen’s transition to the civilian world has made him wealthy. His stake in Doral Energy is expected to bring him $50 million when it debuts on the US market. Yet he remains restless, hinting that political engagement may be next. Scandals, like an alleged affair with a flight attendant, are brushed aside. “I hope the book will show who I really am. Much of my professional life was invisible, a ghost. Now, preparing for public service, I am the opposite—visible, aiming for Israel’s highest office.”

Personal details reveal a man grounded in family and faith. A practicing Jew from a Jerusalemite family, married to a religious nurse, Cohen has four children, including Yonatan, born with cerebral palsy and now an officer in Unit 8200. He supports conscientious military service and backs families of hostages, though he does not personally protest.

Cohen’s charisma is undeniable. In business and social circles, from Kfar Shmaryahu to Ashdod, “everyone is for me,” he says. “Ultra-Orthodox, liberal right, good Likudniks, settlers, family—they show it on their faces.” Long conversations with Cohen leave a clear impression: he commands attention and loyalty, blending intelligence with meticulous public image, yet is still haunted by the compromises of statecraft.

“He is like a balance table,” Cohen says of himself. “Precision and stability are everything. But in humility—if a book is written about modesty, don’t look for my name in the bibliography. Look for me in the finest suit in the room.”