On the drive to Syria, songs of the Golan Heights accompany me.

A region steeped in war, childhood fears at night and deep affection. “My daughter, are you crying or laughing,” “There, the Golan mountains, reach out your hand and touch them,” “My daughter facing the Golan,” “A thousand songs to the north,” “Queen of Hermon.” Even the innocent children’s song “On the top of Mount Hermon,” sung by Chava Alberstein.

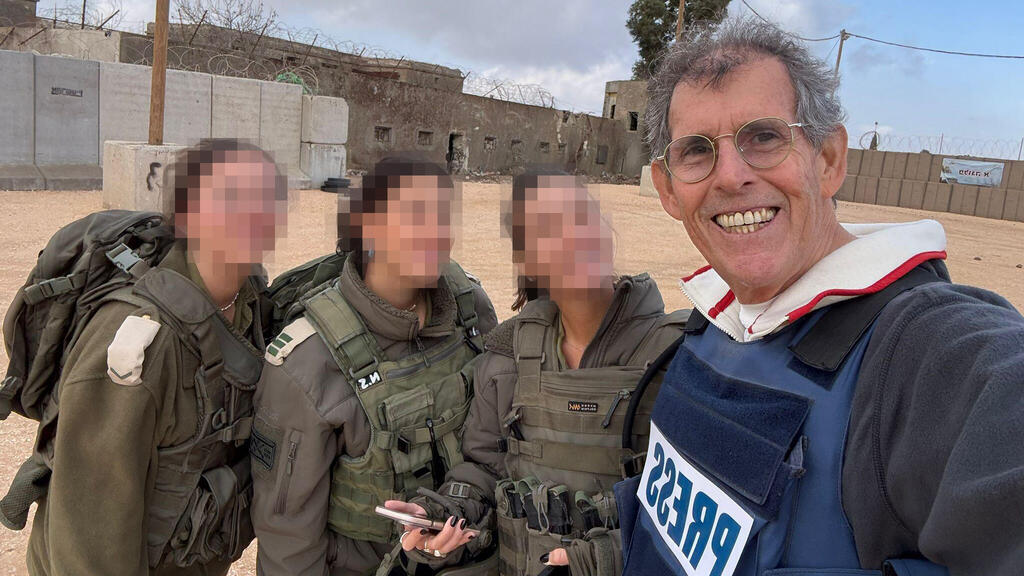

In the car with me are Ynet's journalist and military analyst Ron Ben-Yishai and myself, and we both join the soundtrack like we once did decades ago on youth movement hikes.

When the song “Until Tel Faher” plays, written by Rami Kleinstein after a request from a Golani soldier wounded in the battle for the hill who asked to commemorate what he and his comrades experienced in the Six-Day War, Ron does not hide his emotion.

He was a young paratroopers officer who fought in the capture of the southern Golan Heights during the Six-Day War and was wounded there three years later.

“The glorious hill gathers heroes. If you are from Tel Faher, it shows on your face,” the song says, and I cannot help but think about those days brushing against the present.

Ron, 82, recalls his military service, his wartime experiences and his years as a military correspondent. He knows every curve in the road, and Waze is entirely unnecessary when traveling with him.

Three hours from central Israel, we arrive at the entrance to the division headquarters in Nafah, where we meet Brig. Gen. Yair Palai. He served as Golani Brigade commander from 2022 to 2024 and since May 2024 has commanded the Bashan 210th Division the Syrian front.

On Saturday, October 7, a knock came at the door of his home in the Golan Heights moshav of Keshet. Standing outside was his neighbor, David Zini.

“Palai, the war has started. Organize the brigade,” Zini said briefly. At the time, Maj. Gen. Zini commanded the Training and Doctrine Command and the General Staff Corps

The Golani brigade commander tried to extract details. Was it in the south or the north. Zini answered, “Everything.”

Palai spoke with his officers and headed south.

“We only understood the full picture maybe a week later,” he says. “At the edge of the failure and the insane price, there is one great stroke of luck for the people of Israel. Golani was there. At first, all kinds of chatterers said soldiers were killed in their beds. There is not a single one of ours who did not fight. Headquarters soldiers fought. People put on combat gear over their underwear, boxers, and went up to positions and fought to the last bullet.”

On October 7, Golani lost 73 soldiers, with hundreds wounded.

“It is not easy for people,” Palai says. “They lost many friends, many commanders. There are fears. But as a commander, you manage it.”

He describes constant learning, constant evaluation

“The soldiers go home for the first time during the cease-fire, for Shabbat. There is concern it might pull them back for a moment. Will everyone return. Will fear creep in. Parents’ fears too. I walk among them, look them in the eyes, ask how they are doing. You expect to see weakness or difficulty. But no. Everyone has a very determined look. Every fighter I see, I give him a slap on the shoulder, a pat or a hug, and we move on.”

Standing at the entrance to the division headquarters on the Golan Heights, where the yellow and green colors of the Golani Brigade stand out, Palai speaks to us with absolute clarity.

I ask him whether he brought Golani’s colors here as well. He smiles. “Fortunately, that was done before I arrived.”

Ron Ben-Yishai fought and helped capture the Golan Heights. In my generation, the question was whether the Golan is ours or not. For Brig. Gen. Palai, the question does not exist. He was born there.

This is his land. He is defending his home.

Palai was born 45 years ago in the moshav of Keshet, founded by his parents. He studied at the religious high school in Kiryat Arba near Hebron and knew clearly that he would enlist in Golani as a basic trainee.

He grew up in the Golan until he reached the position of brigade commander.

He ends his chapter in the Golani book with the words: “My Golani is people and victory. That was true before the war. It is certainly true after it.”

The Golan Heights are the childhood landscape of his own family and of his six children, all born and raised among the basalt hills. “This is my quarry,” he says. “I know every path and every grain of sand. I am connected to this land.”

His children, the eldest 23 and the youngest 8, hardly see him despite his service being close to home.

Those who served under him over the years describe a commander of a rare type. He sleeps with the soldiers, goes to sleep last and wakes up first.

Before we climb into the armored jeep of the division commander, Ron Ben-Yishai stops and gives us a brief battlefield lesson.

Here stood Rafael Eitan, a hero of Israel, who saved the country by halting the Syrian army on the Golan Heights. Here this battalion fought, and here another.

Suddenly, our visit to Nafah is no longer just a journalistic tour. It gains context and historical depth.

Brig. Gen. Palai, the division commander, had not yet been born when Ron fought here against the Syrian army. Today, Palai is another link in the chain of heroism and defense of the State of Israel, and I admit that I am moved.

We begin driving toward Old Quneitra.

The mountainous landscape of the Golan Heights is dotted with green oak trees, pine forests and apple orchards. Pastoral and calm. Seemingly so.

When driving on the roads of the Golan, there is no tension or fear like that which grips you the moment you enter Gaza. And yet the quiet on the Golan Heights is fragile. Numerous hostile forces move through Syrian Golan territory, and in an instant everything can change.

Ben-Yishai talks about the fighting in the Six-Day War. I talk about my own injury in Lebanon. The two of us, like elderly Muppets, recounting the wars of this country to the division commander and the IDF spokesperson accompanying us, Lt. Tai.

These wars continue. The heroes change. And thanks to them, the people of Israel endure. That is my conclusion, and everyone nods. What else is there to say.

A barrier that is truly a barrier

As we reach the border gate, Palai instructs us to put on ceramic body armor and helmets.

We are crossing into Syria.

Two Humvees escort us, one in front and one behind, on the road to Old Quneitra, and everything feels surreal.

We are driving inside Syrian territory. Damascus is less than 40 kilometers away. The Syrian Hermon lies 20 kilometers from us. If visibility were better, we could see them with our own eyes.

The sky is covered with clouds. The sun breaks through occasionally. It is very quiet.

No gunfire. Israeli tanks stand in their positions. A fence rises alongside the road, and beneath it an obstacle.

Palai explains that the obstacle being constructed along the border is dug continuously along the entire international boundary.

Its purpose is to delay pickup trucks, motorcycles and vehicles. It is impossible to cross it without placing some kind of bridge, and even that is not simple given how it is built.

If one wants to understand it, this is an obstacle in the style of World War I.

Perhaps here too, after the smart fence and advanced technology, we are returning to basics. An obstacle that is truly an obstacle. A simple terrain barrier.

If a motorcycle or a pickup truck tries to cross, it will simply fall in. The obstacle will certainly delay surprise assault forces and buy time.

Palai is impressive in his decisiveness, which provides a sense of security. And yet, there is a persistent dissonance in the Syrian territory around us. Peaceful quiet and a buried obstacle, alongside moments that could instantly turn horrific.

At times, I have to remind myself that we are in a war zone and that the surrounding serenity is deceptive.

Before our eyes are villages where life froze during a long and brutal civil war that claimed many victims and drove masses of residents from their homes. And not only that war. A succession of conflicts echoes here and in the Israeli kibbutzim we passed along the way.

Most Syrian villages here are abandoned.

Dry fields. Neglected dirt roads. House walls riddled with bullet holes. Rusted barrels topped with car tires used as makeshift fortifications, next to collapsed brick walls.

The few who remain scrape out a living from subsistence agriculture, grazing livestock and above all from smuggling weapons and drugs. Terrorist operatives, militias and criminal gangs hide in the abandoned houses. Chaos has replaced daily life.

As we move freely through territory held by the IDF, it is easy to forget the instability. The fact that the Syrian regime collapsed and that the Syrian state, in effect, no longer exists.

Recently, attempts have been made to rebuild it. There is no certainty they will succeed.

At an outpost known as “the Police” deep inside Syrian territory, I try to find out who chose the name. There is no clear answer.

We meet reservists who have reported for yet another round of service. Maj. Shaked from Ramat Gan is the company commander of the 66th Battalion, which holds the “Police” outpost in Syria. He has already served more than 400 days of reserve duty.

“I started this rotation before Yom Kippur, on September 20, and I am supposed to finish after Hanukkah, on December 25,” he says with a smile. “This is the third year I am celebrating my birthday abroad.”

He laughs: “Without stamping a passport. This year I am celebrating my birthday in Quneitra, Syria, instead of Ramat Gan. Last year it was al-Khiam in Lebanon, and the year before that in Khan Younis. As you can see, I am mostly in reserves.”

“But someone has to do the job,” he adds. “The Syrian sector is different from Gaza and Lebanon. On the surface, not much seems to be happening here, but there are plenty of bad people trying to establish themselves. Our very presence here does everything possible to prevent that.”

Shaked is a fourth-year student at Shenkar College, married for eight months, and planning to celebrate his honeymoon in Thailand when his reserve duty ends.

I ask how one endures more than 400 days of reserve service.

He takes a breath.

“It is insanely hard,” he says. “But when you are here, you understand the importance. The situations are not simple. Every reservist has challenges with their wife, their children, their employer, the university. But we are all here for each other.”

“It may sound patriotic, but it is the truth. It is the camaraderie,” he continues. “I will tell you a story. A few weeks ago, we were supposed to go out on a challenging operational mission. The force required was limited, and not everyone could participate. Everyone argued about who would go, even though we all understand there is danger in every activity, especially in this one.”

“The war is not over. We are not here because it is fun. Even though people in the rear think the war is behind us, here you see and understand that it is not. The guys serving are sacrificing everything, and the home front must understand that.”

Brig. Gen. Palai listens closely. I sense more than a little satisfaction.

“There are reservists here I have known since they enlisted,” he says. “I trained them back in Golani.”

The best of our sons.

He adds that the operational experience accumulated by reservists over the past two years has upgraded the entire army.

Despite the wounded, a success

We arrive in Syria just days after a raid carried out by a reserve paratroopers force from Brigade 55 on the home of a terrorist cell leader from the organization al-Jamaa al-Islamiya in the Sunni Syrian village of Beit Jann, located 11 kilometers from the Israeli border.

As the force exited the village with the wanted suspect and two additional operatives, the convoy of Humvees carrying engineering and paratroopers soldiers was attacked by dozens of terrorists who opened fire.

Around 20 terrorists were killed. Six soldiers were wounded and evacuated by two Israeli Air Force helicopters that landed inside Syrian territory.

“Over the past year, we have arrested terror cells in the sector operated by Hezbollah, Hamas and Iranian elements,” Brig. Gen. Palai explains. “In Syria generally, there are many power centers with competing interests. Druze, Shiites, Sunnis, ISIS, Hezbollah, Hamas and subgroups of armed actors. A lot of threats.”

“The Beit Jann operation was planned over several weeks,” he says. “The reservists from the paratroopers trained on models. We gathered intelligence on the targets and on the village, which is Sunni and extremely hostile to Israel.”

“In the end, we went in to arrest suspects responsible for fire against Israel, from an organization operating against us. After training and intelligence collection, on Thursday night at 2:52 a.m. we entered the village.”

According to Palai: “We arrived in the middle of the night to maintain secrecy and surprise. Brigade 55 carried out the mission after rehearsals with the Humvees. The terrorists were caught in their beds. We surprised them and arrested them without resistance.”

“The operation had artillery, armored and Air force support.”., as we were exiting the village, heavy small-arms fire was opened. By 4:00 a.m. we were already greAen in the eyes. All forces exited the village and the wounded were evacuated.”

“The operation had artillery, armored and Air Force support.”

Still, I ask, six wounded soldiers are hospitalized.

“Because of the preparations and rehearsals, and despite the wounded, this was a successful operation,” Palai says. “We achieved the mission.”

“In every operation we prepare for fire. The army must take risks. That is our role and our essence. We act professionally, and sometimes contact happens. That is the essence, so that we do not meet the enemy at the fence, but in his home.”

“At the end of the operation, the three detainees were transferred to Unit 504. After interrogation, we will certainly learn about additional individuals planning attacks, and it is better to stop them early.”

“In the past, an operation like this would have been carried out by Sayeret Matkal. Today it was a reserve paratroopers force. How did that happen. The reserve forces in the division are all professional, serious and responsible. They do not fall short of regular units in skill. These are reservists who have been fighting for two years in Gaza and Lebanon. Their age, experience and what they have been through turn them into Sayeret Matkal.”

“The activity in the Beit Jann area underscores the importance of proactive counterterrorism in the security zone and the value of forward defense. We must not wait. We must initiate.”

No dramatic lesson, but a clear policy.

What lessons did you draw from the operation?

“We conducted a divisional debrief and are learning from what happened,” Palai says. “It is important to emphasize that the operation achieved its objectives.”

“Yes, we encountered face-to-face contact, a scenario we had prepared for. The forces functioned excellently. We arrived with the full required envelope. There is no dramatic lesson. In the end, this is about policy. The army wants to be the first face the enemy meets, not the home front.”

A few days after our meeting, Palai visited the wounded soldiers hospitalized at Rambam Medical Center. I asked to join him. He declined. He wanted to come quietly, look the soldiers in the eyes and hug them, without turning the visit into a media event. I respected and appreciated the request.

Lt. Tai, the division spokesperson, smiles apologetically and says, “What can I say. Modesty is a supreme value for him.”

We continue driving, passing a Syrian position. Palai explains that Iranian and Russian forces once lived inside this complex. The Iranians were connected to Assad.

We pass the Fork Junction, and he explains that organized Assad army positions once stood here. “We entered and dismantled them,” he says. “Everything was full of army forces that did not allow ordinary civilians to enter Quneitra. The army controlled and managed everything.”

Suddenly, he interrupts himself and points ahead. “That is a Syrian civilian walking toward us,” he says calmly.

I remark that it is surreal. Palai does not make a fuss. These are routine sights in the area.

A minute later, he points to a UNDOF observer watching from his post. “They are still figuring themselves out,” he says.

And the villagers who remain here?

“For the few Syrian civilians who stayed, life is better now than during the civil war,” Palai says. “From time to time we bring sugar, flour and fuel. It is good for them that we are here.”

Do they approach you?

“Some do. Some do not. Every village behaves differently.”

The headline that opens the news

We drive toward New Quneitra.

The shattered statue of Assad still stands at the city’s edge, a reminder of what this place endured. I ask what would happen if we drove deeper into New Quneitra, which today serves as a stronghold of the new regime.

“In principle, we could drive in without a problem,” Palai answers. “We would meet the Syrian police, chat with them and that would be it. There would be no clash.”

When Ron Ben-Yishai asks Palai where all of this is heading, Palai says it is indeed an interesting question.

“I will put it this way,” he says. “Allowing the enemy to grow on our fences and build armies of this scale in Gaza and in Lebanon was a very serious mistake. We told everyone there was quiet. And what is quiet? Something insane grows on your border, and then you have to evacuate 200,000 civilians. That quiet is not worth it.”

“It is better for it to be less quiet. A bit noisier. But not to allow this thing to grow,” he asserts. “The soldiers will continue to separate residents from the enemy and be the first ones the enemy meets.”

“Despite the quiet, reservists are on high alert, defending and ready for developments on the Syrian and Lebanese fronts. The activity in Beit Jann highlights the importance of proactive counterterrorism and forward defense. We must not wait. We must initiate. We will not allow terror to entrench itself along our borders. We will continue to act decisively and proactively to thwart threats and attempts to harm Israeli civilians before they develop.”

Beyond Syria

Things are happening beyond Syria’s borders.

“If I look outside Syria, Houthi and Iraqi militias could try to come here,” Palai says. “The Iraqi militias are a group of crazies who would love to come. But on the way they would likely have to fight the forces of al-Jolani, the Syrian president. He will not let them run so fast.”

That could take years.

“Yes,” Palai says. “But it would certainly be a significant event.”

A few hours later, it was reported that President Trump sent a message to Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

7 View gallery

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and U.S. President Donald Trump

(Photo: Jalaa Marey/ Reuters, Chip Somodevilla/ AFP)

“The United States is not pleased with what is happening in Syria. It is important that Israel maintain dialogue and not interfere with Syria’s development.”

On the drive back to central Israel, I speak with Ron about conclusions from the visit. Without knowing Trump’s statement, he says: “We need to reach some form of coexistence with the al-Jolani regime. There must be a security arrangement.”

As darkness approaches, we begin heading back toward Israel. After all, we are still in Syria.

When I left Gaza for Israeli territory in the past, I physically felt tension ease. My breathing changed. It became calm, normal. That did not happen in Syria.

Perhaps because of the quiet and the pastoral scenery, which in a strange way resembles Swiss calm.

When we reached the car we had left in the parking lot at the northern base in Nafah, the radio news slammed us back into the dysfunction of Israeli politics.

The draft exemption law opened the broadcast. My anger rose.

We stopped for hummus in the Druze town of Mas’ade, and I insisted on holding on to optimism. Throughout the day, I met reservists, right and left, working together to defend this country without politics. Since October 7, they have been grinding through hundreds of reserve days. Despite the hardship, they understand the necessity.

This stands in contrast to politicians promoting a law that allows a large part of the ultra-Orthodox public to avoid carrying the stretcher, placing the burden on one side alone, those who serve.

The indifference and vested interests are infuriating, especially after visits like this. My heart felt like it might burst. I hoped the soldiers we met were not listening to the news.

I think about these heroes, the best of our sons, many wearing knitted kippahs. For me, it is a great source of pride to see the number and quality of these young men. I ask Ron whether he sees it the same way.

“Zionism and stateliness are ingrained in these people in every fiber of their being,” he says. “That is why the original religious Zionists are the ones who remain in career service. They put the state before themselves in the most practical way.”

Brig. Gen. Palai is one of the commanders leading the IDF today, and I envy them.

What does a person want in life? Meaning. Beyond the here and now of their private lives, reservists who report for duty carry meaning that helps them overcome the hardship.

When I ask why they show up again and again, they answer simply. If not them, it will fall on their friend.

These are people from all over the country. It warms my heart.

Ron tells me that at the Police outpost, the company commander spoke with Palai privately and said they needed to carry out a few more operations. He was not deterred by Beit Jann. On the contrary. He has served hundreds of reserve days. He clenches his jaw and knows that a few more operations will provide maximum security to the Israeli home front.

That short conversation is anything but obvious. It is the essence of the human material doing the work there.

I ask Ron for his main conclusion from our day in Syria.

“Clearly, the containment strategy collapsed,” he says. “When a terrorist cell tried to attack Har Dov, the IDF did not act. When Hezbollah sent a terrorist cell to Megiddo, the IDF contained it. That is over.”

“The fact that we are operating inside enemy territory to eliminate threats before they even materialize is the current strategy. The Beit Jann operation and the activity in the villages to disarm people are proof. Prevention is one principle. The second is forward defense. The construction of the barrier and trench along the border proves the IDF will not allow a surprise like October 7 to happen again.”

“The reservists we met today separate Kibbutz Aloni Habashan and the moshav of Keshet from the enemy. That is forward defense. And it means we need many soldiers to implement these two principles in Israel’s security concept.”

As we talk on the drive from Syria, “Song of Comradeship,” written by Haim Gouri during the War of Independence, plays on a loop in my car.

In my head echoes the words of Maj. Shaked: “If you do not come, others will be ground down. You cannot even think of doing that to your friends.”

This is the comradeship of our time.

Over the past two years, I have traveled extensively in Gaza, Lebanon and now Syria. I always ask reservists how they manage to show up again and again. For all of them, the overwhelming consideration for their comrades erases any doubts.

It warms my heart.

I think of the moment when the paratroopers company commander was wounded in Beit Jann, and his fellow reservists ran under fire to extract him, without hesitation.

That is the commitment and profound comradeship we rediscovered on October 7.