It’s been two years. Since that day, life before the war feels like a distant, deceptive memory — a trailer for what became our present. At times, it feels as if it never really existed. Who can even imagine that reserve duty once lasted just two or three weeks a year — a kind of friends’ reunion wrapped in operational tasks?

Today, it’s mostly about preparing for it or recovering afterward. Reserve duty has become the thing itself — the axis around which our lives revolve, even during the holidays. In between, we fake it when we must. Pretend everything is fine. Pretend it doesn’t sting to see how many have already gone back to routine. It’s natural to spend a cumulative year in uniform. That makes sense.

A reality like this changes who and what you are. It shapes your being. Not always in ways you can define, which is why people instinctively look for measurable data: how many divorced, who missed a promotion, what percentage dropped out of their studies. But those numbers tell only part of the story. They lack the feelings, the emotions, the stones piled on a heart full of meaning.

And that’s not surprising. Some things numbers can’t convey. Some nuances can’t be described, even when they’re right in front of you. How do you measure the longing in a child’s eyes? How do you explain pride born in the filthiest of places? How do you quantify disappointment from a boss who stopped understanding? How many faces does a woman’s frustration have? And why, why on earth is it so hard to describe the completeness you feel with your team, your company, protecting home?

This reality isn’t uniform, just as the answers aren’t. They vary as much as the types of uniforms in the IDF today. But in that diversity lies a deeper social process — one that has taken root in Israel over the past two years. It seeps through the graphs into the inner lives of tens of thousands of reservists, for whom the war is no longer a brief interruption of civilian life. It’s always present, even in pauses.

Their transformation isn’t just statistical — it’s in their self-definition, in their personal identity, in their role as human beings in the world. In their dual lives of national service. In the enlistment of their families. In their obligations, decisions, and thoughts.

This group is extraordinary. Far from uniform in opinion, but more united than any other collective. They don’t just guard the borders; they preserve the value of camaraderie sacred to us all. This routine may have been forced upon them, but their role is historic. Most long for civilian life, yet they continue to serve, driven by even a sliver of hope to bring hostages home — because without them, there is no rebirth.

Among them are those wounded in body and soul, yet they are the healthiest part of us. They can’t plan a vacation three months ahead, but they are shaping the reality of decades to come. That’s who they are. Who we are. Half citizens, half soldiers.

This delicate and essential balance — between the khaki hat and the tactical helmet — existed before the war and will remain after it. But at too high an intensity, it becomes an impossible hybrid. And such a state can’t be sustained for long, for one simple reason: our main purpose isn’t only to be good fighters. It’s first to be excellent parents, loving partners, and productive citizens in the miracle called Israel. When that becomes impossible, the ones who suffer aren’t only the reservists’ families, but the entire country.

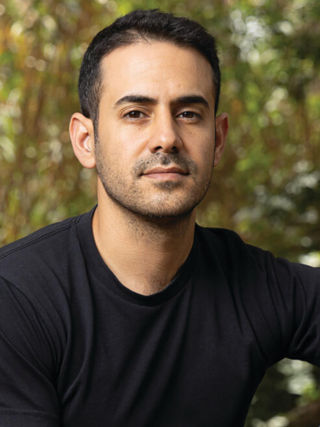

Gadi Ezra

Gadi Ezra Reserve duty is a finite resource. To preserve this treasure, everyone must mobilize. The national priorities must change. Decisive leadership is needed. Otherwise, the outcome is clear: the balance will keep eroding, and soon we’ll no longer recognize ourselves — or the country’s reflection.

Israel’s best years are still ahead. And in that story, we all have a part to play, together. Hopefully, by next year already.

Adv. Gadi Ezra is a former head of the National Information Directorate and an active reservist in the IDF Paratroopers Reconnaissance Unit.