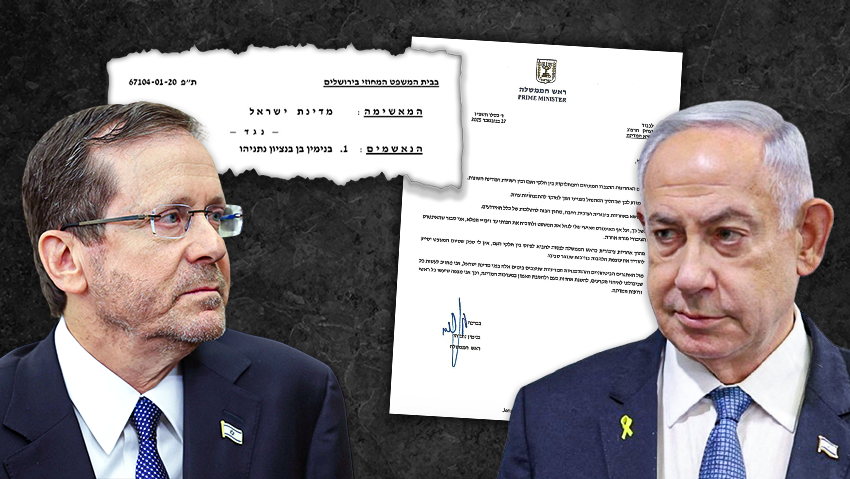

Five and a half years after his trial began, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu dropped a bombshell on Sunday night when he submitted a pardon request to President Isaac Herzog. The move came two and a half weeks after the letter Herzog received from US President Donald Trump.

In a video released after filing the dramatic request, Netanyahu said the continuation of the trial is “tearing us apart from within,” and now the “hot potato” is in the president’s court. There is no doubt it will be the most dramatic decision of Herzog’s term.

But why is Netanyahu seeking a pardon instead of a plea deal, what are his arguments, and why does he need it if, as he claims, “the cases are collapsing”? Here is a breakdown.

What is Netanyahu accused of?

Netanyahu faces charges of bribery, fraud and breach of trust in three separate cases: Case 1000 (the gifts affair), Case 2000 (the Netanyahu-Mozes affair) and Case 4000 (the Bezeq-Elovitch affair).

According to the indictment in Case 1000, which does not include a bribery charge, Netanyahu and his family allegedly received benefits worth about 700,000 shekels from businessmen Arnon Milchan and James Packer.

In Case 2000, which also does not include a bribery charge, Netanyahu allegedly discussed with Yedioth Ahronoth publisher Noni Mozes a deal in which the paper would provide favorable coverage in return for regulatory steps that would harm Israel Hayom, a rival daily.

In Case 4000, the indictment says Netanyahu took, or directed others to take, actions benefiting Shaul Elovitch’s business interests in exchange for sympathetic coverage on the Walla news site. Those steps allegedly generated gains estimated at more than 1.8 billion shekels for Elovitch, directly and indirectly. Netanyahu is charged with bribery in this case.

Are “the cases collapsing,” as Netanyahu repeatedly claims?

No. Unlike Case 4000, which has taken a serious hit, and unlike Case 2000, where it is still unclear how the judges will ultimately rule, Case 1000 appears to have remained largely intact.

Case 1000 has two main pillars. The first, and better known, concerns the alleged benefits Milchan and Packer provided Netanyahu, including cigars and champagne.

The second pillar, less familiar but no less serious, relates to a series of actions Netanyahu allegedly took in his capacity as prime minister and communications minister on behalf of his close friend Milchan. Among other things, the indictment describes Netanyahu allegedly sending former Communications Ministry Director General Shlomo Filber to provide Milchan with private advice on whether the ministry would approve a planned merger between broadcasters Keshet and Reshet, which Milchan sought to pursue.

Why hasn’t a plea deal been reached?

There was previously an initiative to sign a plea agreement in the trial, and even after it was put forward the judges asked the sides to reexamine the possibility. A proposal for a mediation process was also on the table. Both efforts failed.

The reason is straightforward. Case 1000 focuses on benefits and a severe conflict of interest, and any plea deal would almost certainly include moral turpitude. Such a finding would end Netanyahu’s political career. The prime minister has refused to accept that outcome.

What is a pardon, and what happens after a request is filed?

A pardon is a tool in the hands of Israel’s president meant to mitigate the consequences of a criminal proceeding after it has concluded, allowing consideration of broader, noncriminal issues of justice.

Once a request is submitted, it is forwarded by the president to the Justice Ministry’s pardons department for a professional opinion. That opinion is drafted based on information from state authorities and additional views from the State Attorney’s Office. The justice minister also submits an opinion, and the material then goes to the president’s legal adviser, who provides a further assessment. All of this is delivered to the president for a final decision. Any decision can be challenged in the High Court of Justice.

What arguments is Netanyahu making?

Netanyahu argues that even though the criminal process is not over, the president should pardon him for public reasons and in the national interest. He says he is struggling to run the country, especially on diplomatic matters, while having to testify three times a week in court. He also claims a pardon could help heal rifts in Israeli society and end the institutional clash that the trial has fueled.

Has Israel ever granted a pardon before a trial ended?

Yes, once. During the Bus 300 affair in the 1980s, Shin Bet agents killed two Palestinian hijackers after they were captured alive. Then-President Chaim Herzog, father of the current president, issued pardons for murder, manslaughter and obstruction of justice before a police investigation even began.

Under that arrangement, Shin Bet chief Avraham Shalom and other senior officials involved in the affair agreed to resign after admitting wrongdoing and expressing remorse. Petitions against the pardons were filed to the High Court, but the court rejected them, calling such pardons an exceptional tool reserved for cases with no other reasonable solution. Justice Meir Shamgar wrote that only extremely rare circumstances, where an overriding public interest or extraordinary personal circumstances exist, could justify such a step.

If Netanyahu receives a pardon, what happens to Mozes and Elovitch?

The trial is expected to continue against the other defendants, and Netanyahu’s testimony will remain part of the evidence. If he acknowledges wrongdoing as part of a pardon arrangement, that admission could be used against them, and other conditions attached to a pardon could also affect their cases.

Contacts between prosecutors and Mozes over a plea deal took place in the past, and it is likely that if Netanyahu is pardoned, new negotiations with the remaining defendants would follow.

First published: 04:49, 12.01.25