Introduction to this week's Torah portion, Bo

In the Mishnah in tractate Chullin (7:6), Rabbi Yehudah argues that the verse: “Therefore the Children of Israel do not eat the gid-ha-nasheh (the sciatic nerve)” means that the prohibition became active immediately following Jacob’s struggle with the angel, described in Genesis.

In contrast, the Sages posit a different rule: "It was stated at Sinai, but written in its place". Rashi explains that although the commandment was actually given to Moses at Mount Sinai, the Torah places the verse within the story of Jacob, to provide context for the origin of the practice.

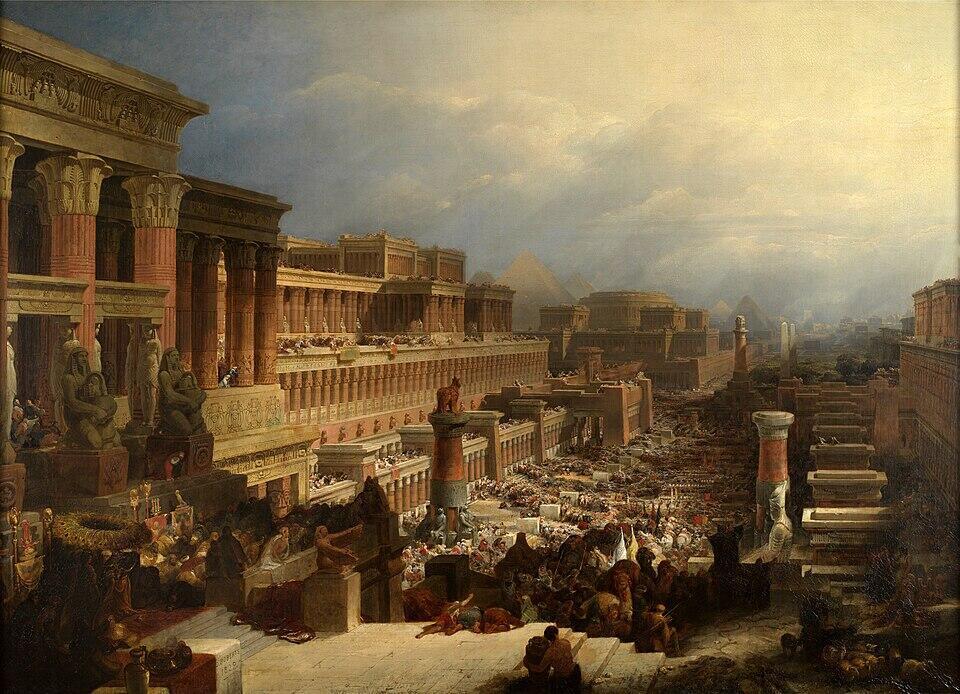

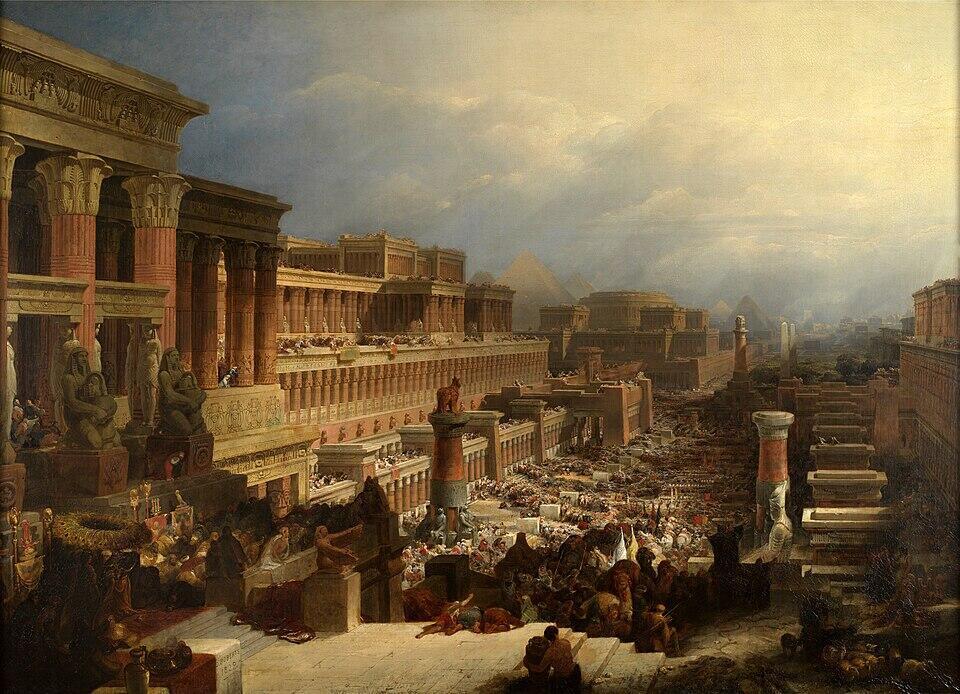

1 View gallery

'Departure of the Israelites', oil on canvas by David Roberts(1829)

(Photo: Courtesy of the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery/Wikimedia Commons)

The chaos of the Exodus and the 'interjected' passages

The narrative of Parashat Bo describes the dramatic and hurried departure from Egypt. Following the plague of the firstborn, Pharaoh urges the Israelites to leave immediately. The text describes a scene of immense commotion: hundreds of thousands of people, and heavy livestock moving in haste, carrying unleavened dough on their shoulders.

Within this whirlwind, the Torah weaves in four dense paragraphs of laws and instructions aimed at future generations once they are settled in the Land of Israel: Exodus 12:13-20-Laws regarding the remembrance of the Exodus, the seven-day festival, the prohibition of chametz (leavened bread), and the obligation to eat Matzah; Exodus 12:43-51-Regulations for the Passover offering, including the requirement of circumcision for participants and the inclusion of the ger (stranger) unlike a resident or a hired laborer who shall not eat of it; Exodus 13:1-10-The consecration of the firstborn and the commandment of Tefillin; Exodus 13:11-16-Reiteration of the firstborn laws and Tefillin, phrased as a response to the questions of future children.

Historically and realistically, it is difficult to believe that the Israelites, amid the haste of expulsion, could have absorbed or even imagined these future complex ritual requirements. Therefore, I prefer to adopt here the Sages' approach that these passages were "stated at Sinai, but written in their place" - intentionally edited into the story of the Exodus itself.

Nation building and the 'national food'

The question then arises: why edit these future-oriented laws into the middle of the chaotic night of the Exodus? I believe that the Torah is emphasizing that the Exodus was not merely a historical liberation from slavery, but the shaping of a new national identity.

A nation is defined by more than just physical freedom; it requires a collective ethos and structure. This is achieved through: controlling the calendar and establishing a unique sense of time; creating shared rituals, such as the Passover offering which demanded the slaughter of the Egyptian idol and served as the first collective ritual; and establishing a distinctive food, specifically matzah, which remains the definitive national food of Israel. Just as Thanksgiving turkey defines an American ethos, matzah - which is still uniquely associated with the Jewish people today - serves as a primary marker of belonging.

Shaping the future in real time

In addition, this 'loaded editing' serves as a meta-message regarding timing: when great events happen, we cannot let them simply 'happen' to us. The lesson from this editorial choice is to be proactive in real-time. As previously mentioned, in my view, the hectic situation caused the Israelites to miss the full significance of the great historic moment. The insertion of so much content for future generations demonstrates that when international-scale events occur, we must analyze where they are leading and how they will shape the future. We cannot wait for the 'dust to settle' to decide what identity shaping we will engage in; we must shape the rituals, texts and values as the events unfold and the opportunities to make an impact remain open.

In next week’s portion we have a call to action once God commanded Moses: “Why do you cry out to Me? Speak to the Children of Israel, and order them to go forward." We are urged not to fear shaping a modern Israeli identity in real-time, blazing new paths that manifest our unique values in a rapidly changing world.