Most iconic Israeli piece of furniture

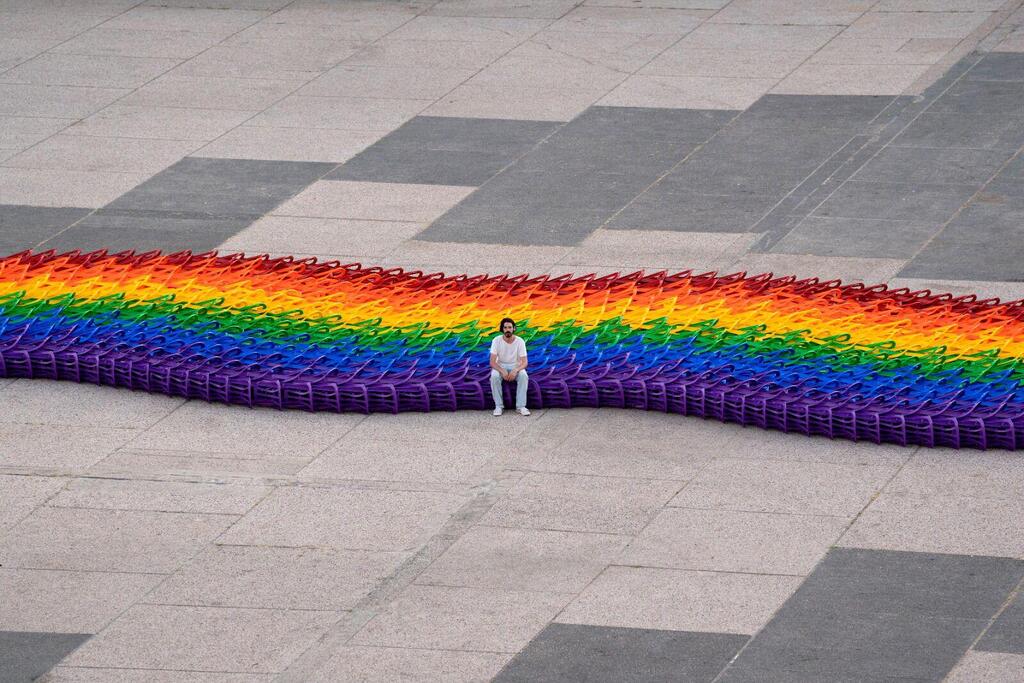

Love it or hate – you can’t get away from the place it holds in Israeli culture: the Keter plastic chair is the country’s best-selling chair. It’s Israel’s unofficial national chair. This lightweight plastic chair has become a must-have at every event, holiday or public space.

It’s also recently become a questionable instrument at every mass brawl documented online. Why? Simply because it’s there. It’s everywhere. It’s a local cultural icon, and like any national symbol, it courts controversy.

“The Keter chair is the kind of product we love to hate,” says Holon Design Museum curator, Maya Dvash. “On the one hand, it evokes a great deal of affection. It looks attractive to us because it’s familiar. You might call it home.

We know what it is, where it’s from and it’s everywhere. On the other hand, it can’t be fixed and it pollutes the environment. At some stage, it came to symbolize all things bad.”

No one ever thought it would become an Israeli icon

So, what’s so special about this chair that is part of our scenery? A Monobloc chair is a plastic chair that has been cast and molded. Its uniqueness lies in its production process: plastic pellets are poured into an injection machine where the materials are then heated and injected into a closed mold in the shape of a chair.

The material solidifies and the mold is opened up, and a chair that is a single unit is born. It needs no assembly. It’s light and can be stacked. It’s cheap and durable - the very dictionary definition of functional design.

“This chair constitutes a rare design achievement – with minimum effort and maximum results,” says Dvash. The first Monobloc chair was produced in Israel in 1985 when plastic producer Keter entered the large product market by mass-producing plastic furniture.

“The chair’s first design was very heavy, less comfortable and less practical. Even at the beginning, it took just one minute to inject a chair, allowing us to efficiently manufacture in large numbers,“ tells us Nisim Eliyahu who was on the development team of Israel’s first Monobloc chair and currently serves as Keter’s chief production manager. Today, it only takes 30 seconds to inject a Monobloc Keter chair and 800,000 such chairs are sold every year.

It's hard to imagine Israel before the Monobloc chair, Israel’s best-selling chair for 25 years. When Keter first launched the chair in the 1980s, the market needed to be “educated".

“We had to convince people that it was okay to sit on plastic chairs,” Eliyahu tells us. “At the time, people wouldn’t bring plastic chairs into their homes. No one thought it would become an Israeli icon. Chairs were made of metal or wood. All that changed the moment people understood they could sit on plastic chairs.”

Only in Israel: We’re all Monobloc

Although global design trends have influenced the Monobloc, it’s very much an Israeli phenomenon. Despite disagreements over who invented the first Monobloc and where that happened, its greatest success to date has been in Israel.

Even the Keter Group, now a global company selling products worldwide, says that it’s a completely Israeli product: “We can’t sell it in other countries,” says Eliyahu.

“Of our 20 plants worldwide, Yokneam is the only one that manufactures the Keter chair. We only sell it to the Israeli market. And they carry on buying it in vast quantities.”

The secret to this success is often attributed to Israeli culture: We like coming together. We love entertaining. The Monobloc chair is functional and unpretentious - very much in keeping with the Israeli ethos.

It owes its commercial success to institutions: You can find it at every cultural event, synagogue, state ceremony, hotel and cemetery. Stacking the chairs at the end of a ceremony is a kind of Israeli ritual.

"In a lot of other places, furniture stays in the family for generations. We don’t do things like that. We’ve consecrated the new over the old. We’re not bridled by tradition”

But we’re not the only people in the world who like hosting. “The main reason that the chair became so popular so quickly in Israel is that we very readily adopt trends” explains Dvash.

“We’re accused of not having a design culture in Israel, or that we’ve rejected it. People arrived in Israel with profound, time-honored cultures of design. But they came here to create something new. It’s hard to imagine a British home, in which furniture is passed from father to son, putting such a piece of furniture in their living room.

In a lot of other places, furniture stays in the family for generations. We don’t do things like that. We’ve consecrated the new over the old. We’re not bridled by tradition.”

Most famous Israeli item design

Few products are so successful that they change not only their own industry, but become a commercial brand. The USB flash drive (known in Hebrew as “disk on key”) is undoubtedly such a product.

You can find this plastic object - that can hold our entire digital world - in every home, office, computer shop or even kiosk in Israel and all over the world. It’s become a basic consumer product.

Patented in April 1999 by the Israeli company, M-systems, the tiny drive, developed by company founder Dov Moran, replaced the old disks bringing about a real consumer revolution.

The USB flash drive offered an alternative to the disks not only in terms of technology: Its simple, compact design that fits in your pocket was what transformed it from a gadget for technology geeks to a global commercial product.

How was the USB flash drive developed?

Necessity is the mother of invention. Moran needed to give a presentation. He couldn’t turn on the computer. There and then, he understood the need to be able to have his presentation in his pocket.

M-systems didn’t invent the flash drive. It had been around for years. The company realized that the USB connection would soon become standard in both PCs and laptops worldwide. They decided to put the flash memory onto a tiny disk that could be plugged into the USB connection.

So simple, convenient and revolutionary. Every industrial designer knows that sometimes, that’s all you need.

Like many tech products that came before, the USB flash drive has started losing ground to the Cloud. And like so many eulogized products, the USB flash drive is, 20 years after its invention, still among the world’s best-selling tech products.

Israel’s tallest building

Reaching 238.5 meters into the sky, and boasting 61 floors, the Azrieli Sarona Tower in the heart of Tel Aviv was launched in 2018 and has already become an Israeli architectural icon.

As Israel’s tallest building, it’s overtaken the three Azrieli towers across the street as Tel Aviv’s architectural icon. At 235 meters, the country’s second tallest building is now the “Moshe Aviv” building in Ramat Gan, with the 187 meters high round Azrieli Tower taking third place.

The tower designed by architect David Azrieli, in collaboration with Moshe Tzur Architects and developed by its successor Danna Azrieli, is visible almost everywhere in Tel Aviv.

The building’s planners clearly wanted to put on a show: Its sheer height and unique twisting geometric design are there to be seen. During construction, you could see passers-by stopping in their tracks at the intersection of Begin and Kaplan streets, one of the country’s busiest junctions, amazed by the height of the building, which looked like it would fall down at any moment. A kind of Israeli Tower of Pisa.

The Azrieli Sarona Tower ranks among Israel’s most ambitious architectural projects: The tower holds no less than 34 elevators spread over 625 to 740 square meters. The average area on each floor is 2300 square meters (that’s just the average.

The twisted design means that the area of each floor varies). A three-story mall sits over seven underground floors of parking lots. Above that are 45 stories of offices, a five-story hotel and three technical stories. Sixty-one in total. International companies renting office space in the building include Facebook Israel, Amazon, Citibank, LABS and Similarweb.

It looks like Azrieli Sarona won’t be dominating the skyline for long. Skyscrapers are taking over the city: The Azrieli group has already started on the Spiral Tower.

On the site where the Yedioth Ahronoth building once stood on Begin Street in Tel Aviv, the Spiral Tower will be 350 meters high, with 91 stories, each with an area of 350 square meters. When the building’s finished in three years’ time, it will be crowned Israel’s tallest building. For now.

Israel’s longest building

The “Quarter Kilometer Building” in Be'er Sheva, as its name suggests is 250 meters long and tells one of the most exciting stories in the history of Israeli architecture. The building in Be'er Sheva‘s “Hey” neighborhood has become iconic – and not necessarily in a good way.

15 View gallery

The Quarter Kilometer Building in Be'er Sheva

(Photo: Courtesy of Moore Yaski Sivan Architects)

In the early 1960s, Be'er Sheva’s “Hey” neighborhood was a kind of architectural laboratory.

The housing project tried to address the challenges of the desert climate in an urban setting. The walls of the long, cloistered, buildings served as defense ramparts against sandstorms. Tightly knit, low-rise buildings stood in the center of the project.

The project itself holds 135 housing units standing on pillars. The building had three kinds of apartments: The first story had two-room apartments, the second story, three-room apartments while duplex apartments were built on the third and fourth stories. The project, like the rest of the neighborhood, was built of bare, unplastered concrete.

Israel’s leading architects of the day were taken on for this massive project: Nahum Zolotov and Daniel Havkin designed rows of patio houses divided by “paths” or “carpets.”

This exposed concrete can be seen in every corner of Be'er Sheva, which architects are trying to brand Israel’s 'Brutalism Capital'

Aharon Bareli and Teddy Kisselov planned the buildings. Avraham Yaski and Amnon Alexandroni planned the northern block, or the wall structure known as the “Quarter Kilometer Building.”

The design wasn’t original. It’s an almost exact copy of the Unite D'habitatio building in Marseille, France designed by Le Corbusier, the father of Brutalism, a style characterized by its use of exposed concrete.

This exposed concrete can be seen in every corner of Be'er Sheva, which architects are trying to brand Israel’s “Brutalism Capital.”

Despite all the innovation and good intentions, this Brutalist building is considered a failure. Whereas the “Hey” neighborhood itself is home to a comfortable population, the “Quarter Kilometer Building” has become a kind of forlorn urban disaster, a symbol of distress and poverty. The project was eventually repurposed as an absorption center. Yaski himself has described the project as an experiment that failed.

The oldest influential active architect in Israel

At the age of 86, Ada Karmi-Melamede is still active and has lots of work. The Israel Prize winner is considered one of Israel’s most important and most influential architects.

With retirement age long behind her, she carries on designing Israel’s biggest and most ambitious projects, most recently the Ne’ot Hovav visitors’ center inaugurated last February.

Karmi-Melamede’s most famous projects include Jerusalem’s Supreme Court building, Beit Haliba in the Western Wall Plaza, the Yad Hanadiv visitors’ center, Beit Avichai in Jerusalem, the Open University building in Ra’anana, buildings at the Ben Gurion University and Reichman University in Herzliya, the Lev Ha’ir building in Tel Aviv. Her office currently employs 18 architects and continues planning new projects.

She was born in Tel Aviv in 1936. Her father was the architect, Dov Karmi, who designed numerous buildings in Tel Aviv’s early years. In the late 1950s she, and her brother Ram, studied at the Architectural Association in London. Together they planned the Supreme Court and further projects.

She taught and worked in the United States for many years, returning to Israel in the 1980s and founding her own architectural company.

Over the years, Karmi-Melamede has created a distinct architectural language that includes total incorporation of light, the subdivision of buildings and the use of local materials.

Many of Karmi-Melamede’s works include a three-dimensional and sculptural experience both inside and outside the building. Sensitivity to light, landscape contour and building materials make Karmi-Melamede’s buildings indivisible from their surroundings. They’re more than buildings. They blend into the topography, deeply connecting with the landscape.

- From most common name to most populated city/ Very best in News

- From the beginning of the internet to 'start-up nation'/ Very best in Teck

- The player who dribbled until the age of 80, and record-breaking medalist/ Very best in Sport

- From deluxe dwellings to humble homes/ Very best in Real Estate

- From The most expensive hotel suite - to most visited nature reserve/ Very best in Travel

- From the longest river to the largest predator/ Very best in Science

- Global swimwear, veteran brand, and designer who conquered the stars/ Very best in Fashion

- The woman who holds record for most marriages/ Very best in Relations