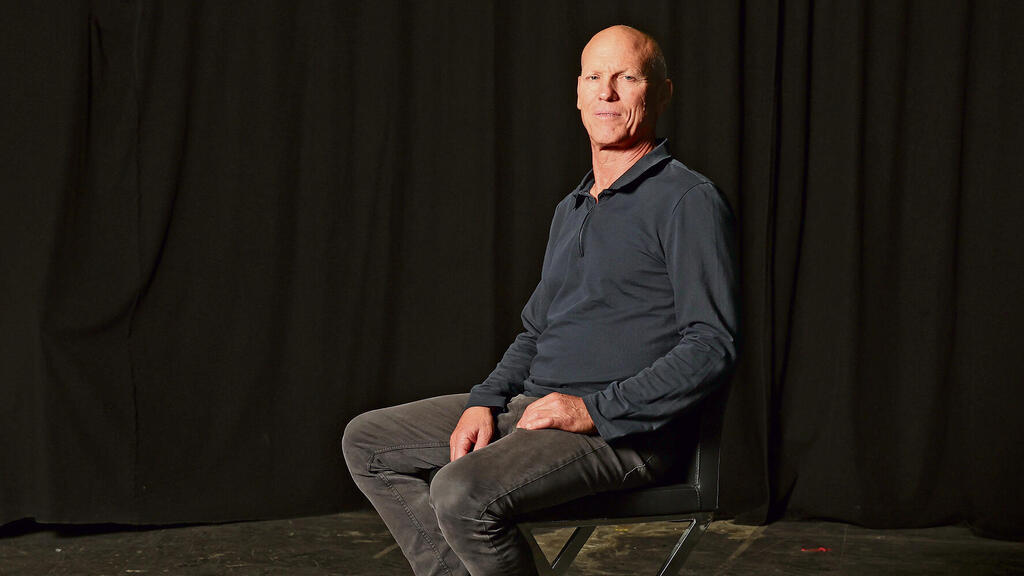

Last week, Sudthisak Rinthalak, the 254th hostage to return to Israel, was brought home. Retired Maj. Gen. Nitzan Alon, who stepped down as head of the IDF’s Hostages and Missing Persons Headquarters, received the news at his home in the south. He described the identification in the same calm tone he used throughout his military career, even as he spoke about an ordeal marked by fear, loss, political pressure and wrenching moral decisions.

In his first interview since leaving his post, Alon said the mission will truly end only when the final hostage, Ran Gvili, returns. He agreed to speak, he said, to acknowledge the thousands of Israelis who worked to bring hostages home. “Write ‘we,’ not ‘I’,” he insisted.

Alon said no one formally appointed him on Oct. 7. After calling officers he knew in Military Intelligence, he was told their units would take responsibility for locating and returning the hostages and asked if he would join. That night, an improvised command center was assembled. “We pushed in 100 computers,” he said. “By Sunday, more than 100 people were already working.” Over the following days, the framework became formalized. Alon said he had almost no contact with then–IDF chief of staff Herzi Halevi at first: “He was extremely busy. I didn’t interrupt him, and he didn’t interrupt me.”

The effort began with 3,146 missing people, many later found dead or hiding. Twelve remained unaccounted for for months, either because their bodies were destroyed in fires or because they were taken to Gaza. After weeks of work, 251 were confirmed as hostages, later joined by the long-held captives Hadar Goldin, Oron Shaul, Avera Mengistu and Hisham al-Sayed.

Alon said that on Oct. 7, “Anyone who tells you they understood the full picture that day is not telling the truth.” The shock, he said, was national. His team spent the first days organizing information streams they called “blue intelligence” — material from social media, stolen terrorist cameras, police footage and testimony from evacuated communities — and “red intelligence,” gathered inside Gaza by Military Intelligence, the Shin Bet and other units. Both included graphic evidence. At the height of the effort, some 2,500 people contributed, with about 500 active at any given moment.

Three weeks after the attack, as the IDF’s ground maneuver began, the team had a rough sense of some hostages’ locations, but Hamas frequently moved them. Several hostages died after reaching Gaza alive, often during heavy fighting. Alon recounted the death of Tamir Nimrodi, killed in an airstrike on a building where Israel did not know he was being held. Another hostage, Chen Goldstein-Almog, survived after the building where she was held was marked off-limits for Israeli strikes; a nearby blast shattered windows and shook walls. “The fear caused by our own airstrikes came up again and again in hostages’ accounts,” he said.

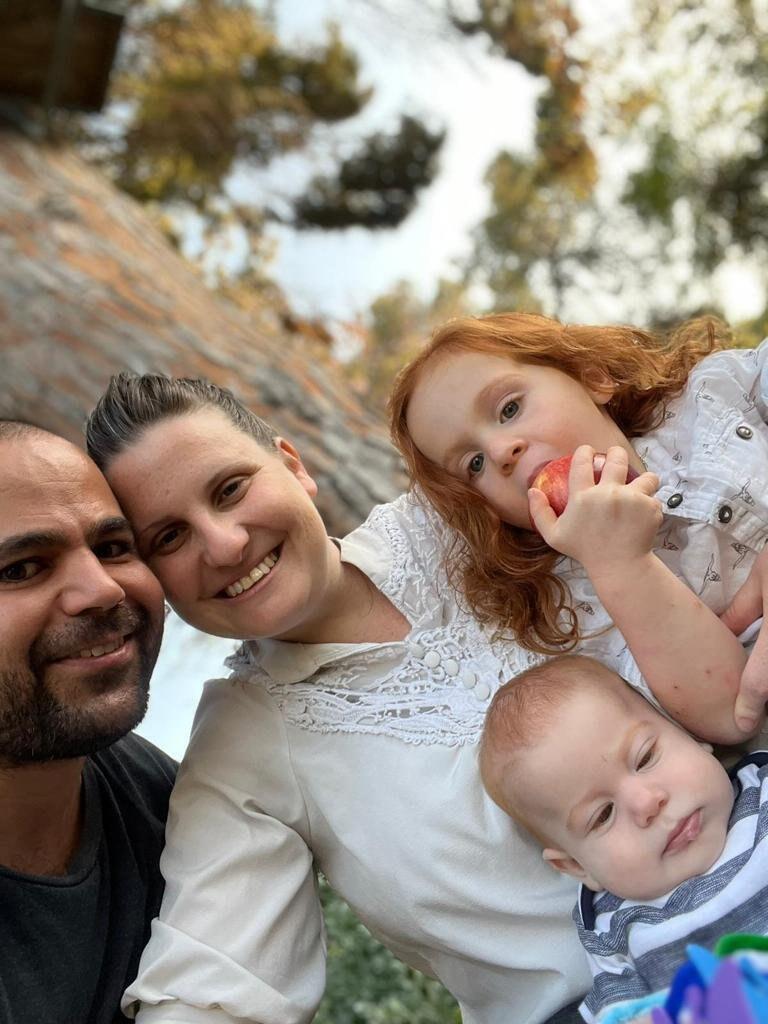

Confirming deaths without bodies required extensive intelligence work and religious authorization. The headquarters created a category called “Most Probably Dead,” and the Chief Rabbinate established procedures for civilians. “We told Hamas who abducted the Bibas family,” he said, hoping pressure would lead to the return of their bodies.

From the start, multiple foreign actors were involved. Former U.S. president Joe Biden pressed Qatar to help secure the release of American citizens Natalie and Judith Raanan. Qatar delivered. Egypt then sought to demonstrate its influence, helping secure the return of Yocheved Lifshitz and Nurit Cooper. Russia, Alon said, made attempts but succeeded in freeing only one hostage, Roni Krivoi.

Alon said Israel’s government had minimal involvement in the first major hostage deal in November 2023. “The government was busy with other matters,” he said. “Mossad chief David Barnea and I had almost full freedom.” That changed in later months, with cabinet ministers intervening repeatedly. Alon acknowledged he traveled only when he believed talks might advance, though he still attended two unsuccessful rounds in Paris and Warsaw.

Internal competition between Qatar and Egypt shaped much of the mediation, he said, while Hamas leaders maintained a clear hierarchy, with Yahya Sinwar serving as the ultimate authority. American involvement under President Donald Trump was markedly different. Alon said then-CIA director Bill Burns had limited effect because mediating states did not apply enough pressure on Hamas. “They told Hamas the hostages were a burden. Sinwar didn’t agree. To him, each hostage had value.”

The headquarters created a large system for communicating with families, aiming for transparency except where information threatened security or hostages’ privacy. In rare cases, families were told their loved ones were alive before intelligence confirmed they had died. “Those were devastating moments,” Alon said.

He said mass protests in Israel had “far less dramatic impact on negotiations than many claimed.” Hamas initially believed demonstrations strengthened its position but later understood they did not.

By late 2023, the headquarters’ recommendations influenced IDF operations to reduce risks to hostages, sometimes creating tension with field commanders. “Formally we didn’t set boundaries; in practice we did,” he said. The most painful moments for the team, he added, were the killings of six hostages in two incidents in Khan Younis and Rafah. On the accidental killing of three other hostages — Yotam Haim, Alon Shamriz and Samer Talalka — by IDF troops in December 2023, he said the incident stemmed from flawed assumptions on the ground.

Alon said all hostage deals under discussion envisioned phased releases. In November 2023, Israel persuaded Hamas that hostages under 18 who had not yet enlisted should count as minors, raising the number of eligible children. Sinwar later tried to classify seven women as soldiers to halt their release; Israel refused. The deal stalled because Hamas withheld those women and because Israel’s cabinet voted to resume the war regardless of Hamas’ offer. Alon expected negotiations to resume after a few days of fighting, but talks froze for months. Humanitarian steps that might have restarted dialogue were repeatedly rejected or delayed. As a result, dozens of hostages — including 24 Thai citizens Hamas had intended to release without conditions — remained captive for another year.

Alon said he considered resigning amid the stalemate but decided remaining in his post would help more hostages return home. “If I had left, I’d be eating myself alive,” he said.

The January 2025 agreement was finalized with the involvement of Trump envoy Steve Witkoff. When Hamas demanded an additional Israeli pullback inside Gaza, Israel refused but agreed to release ten more Hamas prisoners. “What mattered was securing a deal,” Alon said. He credited Trump adviser Jared Kushner with playing a decisive role in the most recent agreement, saying he is viewed in the region “as a prince,” with strong influence in Arab capitals.

Alon expressed skepticism about an emerging American vision for a rebuilt Gaza made up of new towns without refugee camps. “You can’t take someone from Beit Lahiya and tell him he now lives in Rafah,” he said. “Gaza is traumatized but hasn’t forgotten everything. Hamas will not give up easily.”

He said Israel began the war with the principle “hostages first; Hamas later,” but the government chose a different path. Whether the war’s cost will be judged worthwhile, he said, depends on one outcome: “If Hamas remains in power in Gaza, we achieved none of our goals. If it is dismantled, people will still debate the price — and many will argue a similar agreement could have been reached much earlier.”