For years, a time bomb wrapped in a plastic bag lay hidden in the attic of Avraham Russek’s home in Ra’anana.

Inside the plastic bag was a secret report his father, Chief Superintendent Menachem Russek, handed him in the final year of his life. He was angry and exhausted after years spent chasing Josef Mengele, his personal white whale.

Only unlike Herman Melville’s novel, Russek’s whale wore white gloves.

The ending, in both cases, was the same. The hunter died before the hunt was completed.

Even 80 years after the end of World War II, the name Mengele still inspires terror. It is synonymous with absolute evil. A dual symbol of Auschwitz as another planet and of the escape of Nazi criminals from justice.

The renewed storm surrounding Mengele’s legacy came from Argentina, one of the places where the Angel of Death of Auschwitz-Birkenau hid. The documents published there reminded Argentines of something many preferred to forget. For decades, the authorities knew where Josef Mengele was and did nothing.

The Argentine documents were released in April by order of President Javier Milei, but only at the beginning of this month did the full picture emerge. From 1956, Mengele lived openly in Buenos Aires under his real name. In a formal application to change his name, he declared his membership in the SS and noted that the Red Cross defined him as a war criminal. The authorities ignored this. Later, they also rejected an extradition request from West Germany.

Russek, a man who never spoke to his children about his work, offered little explanation when he entrusted the report to his son.

“He said, ‘This is top secret, and no one should know it is here,’” Avraham Russek recalls. “I put it in the attic. I only read it after he died. It was like a thriller.”

Russek’s children and grandchildren have lived for years with the sense that a grave injustice was done to him. The man who insisted that “various forces joined hands to conceal the truth,” and who pointed fingers at both Israel and the United States, never lived to see his theory move from the margins to accepted fact.

He died in 2007, angry and frustrated, without seeing the vindication.

“My father was angry all the time,” Avraham says. “Until he died, I carried his anger with me. It affected my health.”

His granddaughter, Niva Russek-Blum, remembers it clearly.

“He was a very good grandfather and we were very close,” she says. “But I remember the intensity of the anger. As a child, you see someone you love so much and how much anger comes out of him. He felt that something was happening that he could not control. Forces. He would just say, ‘The state.’”

Did your father have a theory as to why Mengele was left alone?

“Yes,” Avraham says. “After the war, the Americans took many Nazi scientists, brought them to the United States and used them. That was one of his ideas. My father said that the State of Israel, together with interested parties in the United States, joined forces to conceal the real facts of the Mengele story. He believed he would prove that there was an opportunity to capture him, and that someone deliberately failed and covered it up. He died with that feeling.”

Is there any sense of catharsis now that the documents are public?

“The only catharsis would be if we understand what really happened,” Niva says. “If the state was involved in this cover-up. Who wanted to remove him from his position. It troubles me. If I understand what happened, maybe there would be some relief.”

Avraham is not comforted.

“Happy? No,” he says. “I am very sad that my father died without knowing that the truth he fought for would come out 18 years after his death. The documents do not prove the body was not Mengele’s. But they do show that other countries were involved in protecting him. Mostly, I feel sadness. I wish this whole thing had never happened.”

What do you think he would say if he were alive today?

“Maybe from the small cloud he is sitting on now, looking down at us, he is finally saying, ‘You see? I told you.’”

There are things that cannot be explained without returning to the beginning.

And Russek’s beginning has a name. Auschwitz-Birkenau. And another name. Josef Mengele.

For him, they were one and the same, because they entered his life together.

He was born earlier in Lodz, but part of him died and was reborn in 1944 on the ramp at Auschwitz-Birkenau, facing the doctor who sent his mother to the left, to rise as smoke into the sky.

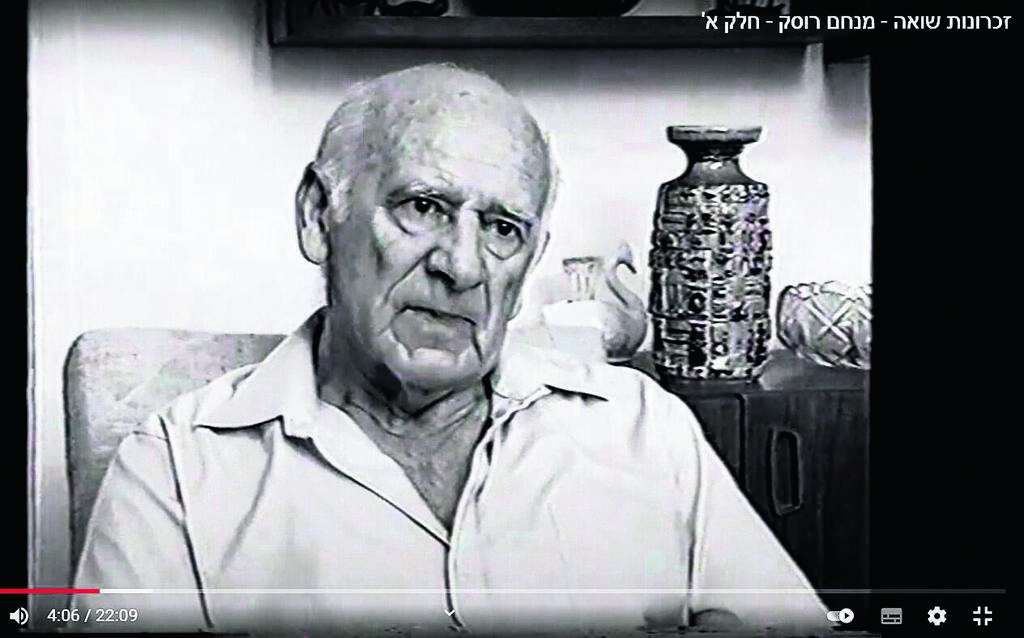

“We did not say goodbye,” he said in testimony he later gave to Yad Vashem and the Spielberg Foundation. “Nothing. Nothing. The blows, the pushing, the shouting, they just pulled us apart. We did not know what was happening.”

Only later did he learn what happened to his mother, and that the doctor on the ramp was named Mengele.

He immigrated to Israel, married, built a career and a family. And all those years, he did not speak about what he went through in the Holocaust.

His son Yossi recalls that a story once appeared in a police newspaper. “There he talks about how I asked him about the tattoo on his arm and he did not want to answer,” Yossi says. “I asked him why he was ashamed, and he was ashamed. They were all ashamed.”

The Eichmann trial was the first time Holocaust survivors in Israel began speaking publicly about what they endured, without the humiliating label of having gone “like sheep to the slaughter.”

But Russek remained silent.

A man who was not inclined to words to begin with, he continued to keep quiet. When he did speak, it was only about solid facts and investigative material, never about emotions.

“My father would ask him, ‘What did you feel,’ and he would get angry,” Russek-Blum says. “He was extremely analytical, a man of details and facts. Emotionally, he was blocked in some way. He did not talk about what he went through, and certainly not about what he felt. He would say, ‘What did I feel? Who could feel anything under those conditions? It was just survival.’”

At the time, Russek’s anger was directed at sabras, native-born Israelis, the lucky ones who, as he said in testimony to Yad Vashem, “did not know what they were talking about. What, were you there? What do you know? I did not want to get into an argument about this subject.”

Later, he said, there was no need for arguments. People learned what happened.

They learned it through the Eichmann trial and later through numerous convictions of Nazi criminals, cases in which Russek was involved as commander of the Nazi Crimes Investigation Unit of the Israel Police.

The unit’s mechanism was simple and efficient. A foreign country located a Nazi criminal, sought to bring him to justice and sent the details to Israel. Investigators from the unit, most of them Holocaust survivors themselves, went into the field. They located witnesses, persuaded reluctant survivors to speak and took testimony. They then accompanied the witnesses to trial, sometimes all the way to the witness stand in Germany.

The investigators were not Israel’s elite Mossad operatives, trained for dramatic kidnappings under cover of darkness. This was exhausting, often gray work. Convincing survivors who did not want to reopen wounds. Collecting details with painstaking care. Filling out endless reports.

But this work, lacking any glamour, led to the convictions of Franz Stangl, commandant of Treblinka, and Klaus Barbie in France. Investigators from the unit testified hundreds of times in trials of Nazi criminals and even helped establish a parallel unit in Australia.

In Israel, they were involved in the pursuit of Josef Mengele and in the Demjanjuk trial, two cases that would later become personal traumas for Russek as the unit’s commander.

Despite its historical importance, even at the height of its activity, the unit was not widely known. After it was dismantled in 1993, it was almost entirely forgotten. A comprehensive investigation published in April 2022 revealed the full scope of its work. But as often happens, what disappears from collective memory can be more telling than what remains.

Russek commanded the unit for 13 years, its golden era. During that time, dozens of Nazi criminals were convicted. Russek himself became a well-known figure among colleagues in foreign countries.

But Russek knew that the one man he truly wanted, Mengele, remained beyond his reach.

Then, in 1985, he was told that perhaps he would not need to catch him after all.

After years of effort by Russek’s unit and cooperation with German and American teams, including the announcement of a generous reward for the doctor’s capture, a body was found in Brazil.

The world decided it was Mengele.

An international team, German, American and Israeli, was assembled to identify the skeleton. Rossek flew to Brazil.

“When I started interrogating the people in Brazil, I saw them,” he said in testimony to Yad Vashem. “Those Nazis who hid Mengele. I did not believe for a moment that he was dead, supposedly as they determined there.”

In the report he wrote, a product of meticulous attention to detail fueled by a deeply personal motive, Rossek documented a series of contradictions.

Liselotte Bossert, who helped hide Mengele along with her family, was present at the alleged drowning. She called an ambulance before the body was retrieved from the water. The ambulance took three hours to reach the forensic institute located 30 kilometers from the shore, she claimed, because lightning struck a tree.

The duty doctor at the pathology institute did not perform an autopsy or collect identifying markers. He also failed to notice that the identity card listed the deceased as 54 years old, while the body before him, if it belonged to Mengele, was 68.

Marwell remembers Russek with warmth.erican investigative team in Brazil, later became a leading expert on the Mengele affair. The book he wrote overlaps in many places with Russek’s arguments, but regarding the skeleton itself they agreed to disagree. Ruussek insisted the body was not Mengele’s. Marwell became convinced it was the Auschwitz doctor.

“There is a very subtle change in how the Nazis defined the role of a physician, and it relates to who and what is the object of treatment,” Marwell explains this week in an interview. “For a doctor, the patient is the only object of care. For the Nazis, there was a larger patient, and that was the racial body, the Volk. As a Nazi doctor, you were responsible not for healing an individual patient, but for ensuring that the racial community was protected from threats and treated accordingly. It is a much bigger picture.”

As for claims that the Americans had an interest in protecting Mengele because of his medical knowledge, Marwell rejects them.

“Mengele’s research was not at the forefront of genetics,” he says. “If the Americans were looking for outstanding geneticists, there were others among the Nazis. Mengele, with all due respect, was not one of them. What he did have was a massive experimental field called Auschwitz.”

Marwell remembers Rossek with warmth.

“I liked Russek very much,” he says. “He told me about the difficult childhood he had in Poland and about his connection to Mengele. When we first arrived in Brazil, I sat next to Russek. He was very modest and very quiet. He did not say a word. He certainly did not openly oppose the experts’ findings, but he was clearly conflicted.”

That restraint did not last.

“All of that disappeared later, when he spoke to journalists and said something like, ‘Mengele wanted to dance on my grave. Now I will dance on his,’” Marwell recalls.

The next time Marwell returned to Brazil, Russek was no longer there.

“I understood that he had been removed from his position,” he says.

In his book, Marwell describes how an appeal by the Wiesenthal Center to President Ronald Reagan, demanding that “the Mengele file held by the military be opened,” led to testimony from a former soldier.

In July 1945, while stationed in Germany, the soldier encountered a German prisoner who identified himself as Josef Mengele. Guards told him they were “getting the prisoner in shape for hanging.” The soldier later recalled being told, “That son of a bitch Mengele sterilized 3,000 women in Auschwitz.” The prisoner was later released.

Does that not suggest American assistance?

“In hindsight, there were many problems with that testimony,” Marwell says. “Today I have to say that we found no unequivocal evidence that he was part of an organized escape route or that he received assistance from the Americans. They thought he was dead. I do not think the Americans can necessarily be blamed for not finding him.”

When the investigative team in Brazil announced that with reasonable scientific certainty the body was Mengele’s, the State of Israel decided to accept the recommendation and close the file.

“I have material in three binders that proves the opposite,” Russek said at the time. “The body is not Mengele’s. This is a fraud unlike anything seen before.”

Rossek concluded in his report that the purpose of the drowning operation was to bring about the final burial of the Josef Mengele affair, including the neutralization of all those who knew the secret.

No one listened.

And not only did they fail to listen. According to Russek, there were those who actively interfered with the investigation.

Regarding American involvement in protecting Mengele, Russek was unequivocal. In his report, he wrote that the Mengele file disappeared from the Berlin Documentation Center in 1985, while under American supervision and guarded by German police.

It later emerged that all personal files had been photographed by United States authorities and were stored in the National Archives in Washington. Identifying materials such as fingerprints and X-rays were never found anywhere.

Russek claimed that documents also disappeared from his own office.

The pathologist Dr. Shmuel Rogev, who worked with Russek on the identification and supported his position, was removed from his post shortly after Russek retired. According to Russek, materials related to the investigation were also taken from Rogev.

“All the material was taken from him,” Russek said in testimony at Yad Vashem. “And a few months later they told him, thank you, you can go home. They neutralized him too. That was the number one disappointment. To tell you the truth, it is a shame that this ended this way, especially here in Israel.”

Russek described a conversation he had with a member of Knesset who served as chairman of the Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee.

“I told him that one day, when Mengele appears somewhere, he will start dancing on the table, the file that you closed,” Russek said. “I told him explicitly, do not dare close this file. It will be a disgrace to the State of Israel.”

What did the lawmaker reply?

“He told me, do not worry about the disgrace of the State of Israel. That hurt me more than anything else.”

In retrospect, the failures of the Mossad in the Mengele affair appear almost impossible to comprehend.

Various explanations were offered over the years, including manpower constraints and shifting priorities, but the result was the same. Mengele was forgotten, went deeper underground and disappeared from Israel’s radar for another 20 years.

Former Mossad official Rafi Eitan, who was involved in the capture of Adolf Eichmann, said in interviews toward the end of his life that in the 1960s he came face to face with Mengele on a small farm near Sao Paulo. He said they were ordered to return to Israel because of another urgent threat. Egypt was developing missiles with the help of German scientists.

In 1991, the newspaper Hadashot reported that Israel had shelved a 1986 report concluding that Nazi criminal Josef Mengele was alive. The item had no follow-up.

Dr. Tamir Hod, a Holocaust historian and author of “Why we remembered to forget: the Demjanjuk trial in Israel,” explains why.

“There were so many factors here that preferred not to deal with it,” Hod says. “It may have been more convenient to leave him as an abstract symbol of absolute evil, rather than confront how many failures there were along the way.”

“I think the part that hurt him the most was the possibility that Israel itself was involved,” says his son Yossi. “He was in Auschwitz. He passed through Mengele’s hands. For him, it was something deeply personal. It hurt him immensely.”

There are people who believe that if you arrange the details of a story correctly, if you are precise enough, if every piece of data is placed exactly where it belongs, the truth will emerge.

Life does not always work that way.

The historian Raul Hilberg once said, “In all my work, I never began by asking the big questions, because I was always afraid I would arrive at small answers. I preferred to deal with tiny details, so that later I could assemble a fuller picture, which, if not an explanation, would at least be a more complete description of what occurred.”

Menachem Russek was exactly that kind of person.

He did not tell his story through words or emotions, but through an album of photographs he prepared himself for his family. It was meticulous and analytical to the point of pain. Every year, every place, every photograph arranged in exact chronological order.

His granddaughter Niva Russek-Blum, who holds a doctorate in neurobiology from the Weizmann Institute, attributes her love of detail directly to genetics inherited from her grandfather.

“The most precise, the most historical,” she says. “That was his way of telling what he could not tell in words.”

Perhaps this is why, in the final year of his life, Russek asked his family to hide the report he had written on the Mengele affair.

Even after his forced retirement from the police. Even after the case was officially closed. Even after there were hints that the country’s leading Nazi crimes investigator had lost his judgment.

He continued to speak about Mengele, about the report and about the system that slammed the door in his face.

He wrote letters to members of Knesset and to colleagues such as David Marwell and others. He pleaded, insisted and grew angrier, until finally he faded in deep sadness.

Russek-Blum says that the disappointment with the state was a turning point.

The man who saw Israel as the place that gave him back an identity and a life could not reconcile that ethos with his personal disappointment over the state’s conduct in the Mengele affair.

“He came with a plastic bag containing the report and said, ‘This is top secret, and no one should know it is here,’” Avraham Russek says. “I put it in the attic. I only read it after he died. It was like a suspense novel.”

Avraham recalls another moment.

“One day he came with a plastic bag, which we later understood contained the report he had written, and told me, I do not want this in my house,” he says. “I did not know what it was. He only said, ‘I do not want this to be found in my house. It is top secret. No one should know it is here.’”

Was there ever a moment when the family doubted him? When they thought he was exaggerating or going too far.

“We never felt that,” Avraham says. “There was a general sense of injustice, a feeling that the state was hiding something.”

There is injustice, and there is persecution. In the end, Russek was haunted. The question remains by whom.

“He was completely haunted,” Avraham says. “Objectively, I cannot say by whom.”

And yet there was one moment in Russek’s life when revenge and reality did not collide.

A single moment when, briefly, he was whole.

His son Yossi recalls the wedding of one of Russek’s granddaughters, not long before his death. They stood together for a family photograph. Around him were his children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

“Suddenly, he began to cry,” Yossi says. “When they asked him why, he said, ‘This is my revenge on Mengele. My family.’”

Years earlier, in testimony to Yad Vashem, Russek expressed the same thought in different words.

“I built a new family and new generations in the State of Israel,” he said. “That is my consolation.”

To understand Mengele’s place in collective memory, one must first understand Auschwitz, says Dr. Tamir Hod, head of the Tel-Hai Center for Holocaust Research, Education and Commemoration.

“Mengele gave evil a face,” Hod says. “If Auschwitz symbolized absolute evil as a place, Mengele symbolized it as a person. Public discourse often needs a face.”

Another reason for Mengele’s demonic status, Hod explains, is that between late April and July 1944, hundreds of thousands of Jews from Hungary arrived at Auschwitz.

“Aside from Rwanda, this was the fastest rate of mass murder in history,” Hod says. “And Mengele was there.”

He was not the only doctor on the ramp, Hod notes, but he was the one etched into memory.

And yet public engagement with the affair in Israel remained limited.

“The figure was so monstrous that it was almost unreachable,” Hod says. “Many forces preferred not to deal with it, because then it would have been exposed how many times it was actually possible to catch him.”

It turns out that not only the Mossad tried.

Following an earlier investigation published in this magazine about the Nazi crimes investigation unit, Hod received a phone call from an anonymous source. The caller described a group of Israeli civilians, led by a former Mossad officer, who organized in the 1980s to kidnap Mengele on their own initiative.

According to the source, the group received approval from a senior government figure and funding from Jews in the United States and Australia. They came close. They saw him through binoculars in Paraguay, surrounded by bodyguards. But they were not certain it was Mengele, and the operation was aborted.

In 2013, the biography “Abysses and skies” revealed that in 1984 Israeli pilot Zeev Liron joined a private operation initiated by former Mossad and Shin Bet officer Zvi Melchin. The goal was to kidnap Mengele. The operation was based on faulty intelligence and never went ahead. It was later discovered that Mengele had died in 1979.

Hod, who has accompanied the Russek family since his earlier research on the unit, is preparing to publish a book titled “Menachem Russek and the Nazi crimes investigation unit of the Israel Police: a case of legal revenge.”

Still, he urges another perspective on the Mengele conspiracy.

“It is not that there was no cover-up,” Hod says. “There was one, and it is proven beyond any shadow of a doubt. But at the same time, other things were happening in the world that influenced the fact that Mengele was not captured.”

Israelis, he says, must understand, as difficult as it may be, that what feels existential and explosive here does not always feel that way to someone sitting in Washington or London.

He quotes Allen Ryan, one of the heads of the US Office of Special Investigations, who said after the war, “We killed Hitler. Now we have Stalin.”

“The Cold War changed Western priorities,” Hod explains. “It was not that someone said, ‘I am letting Mengele go.’ But the general policy toward Nazism affected all the components.”

And Russek.

“Anyone who follows his activity understands that he did not do this out of populism,” Hod says. “It was a genuine mission, and he was responsible for many convictions of Nazi criminals. What he claimed, that various forces covered up the story, is today proven beyond any doubt.”

Then he adds one final sentence.

“At the same time, we tend to forget that we are not the center of the world. Not everything is against us. There were other factors.”