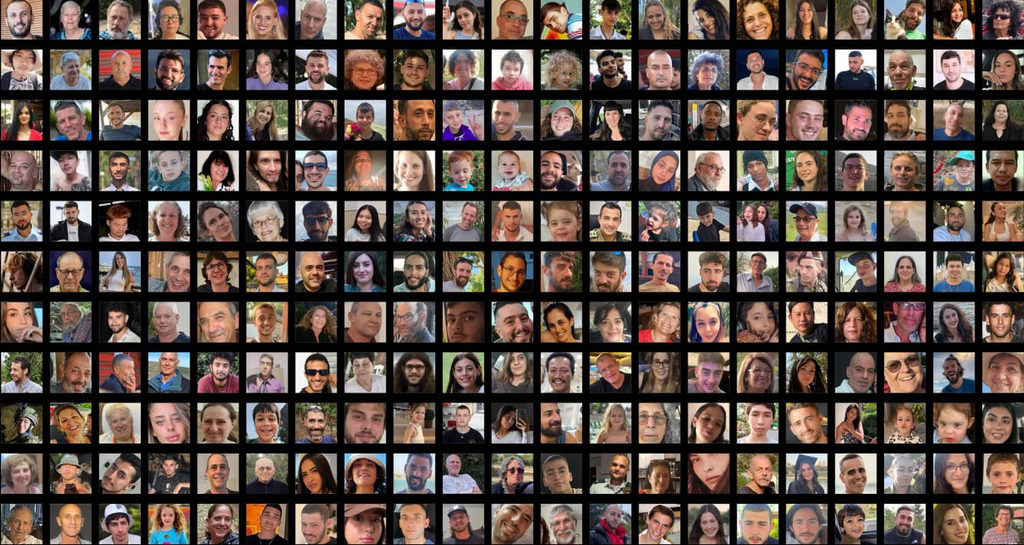

Hamas’ surprise attack on Oct. 7 and the murderous massacre carried out by its terrorists left the IDF and security services stunned. Reports of atrocities and the takeover of civilian communities and military bases shook the country, compounded by an unprecedented wave of kidnappings into the Gaza Strip.

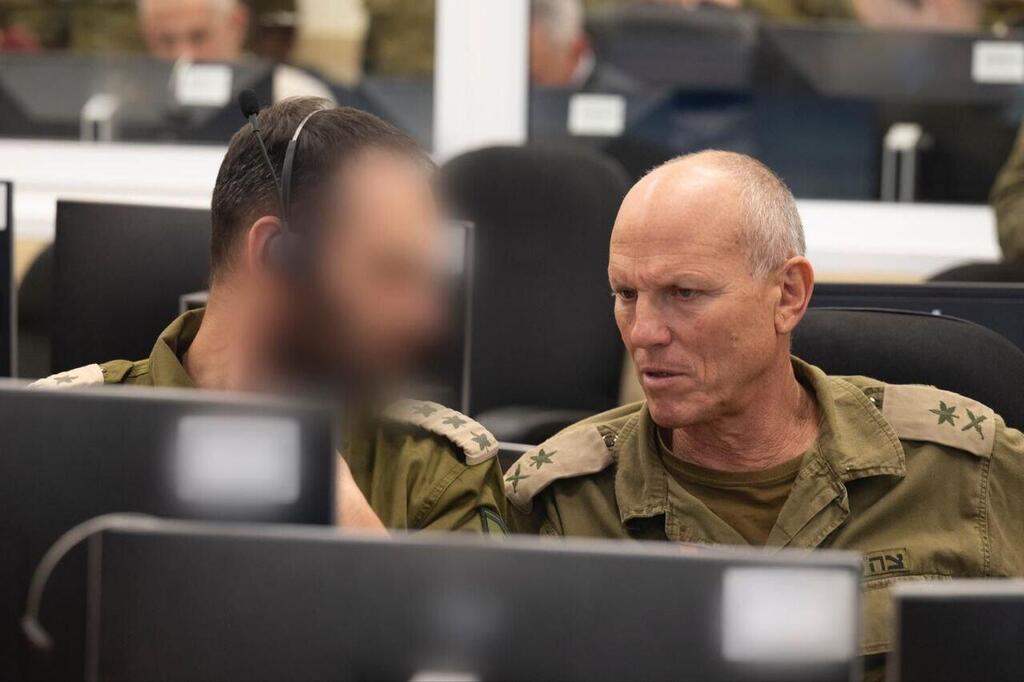

Within a short time, under a cloud of mourning, shock and uncertainty, the IDF established a Hostages and Missing Persons Command under the leadership of Maj. Gen. (res.) Nitzan Alon, a retired senior officer recalled to service.

This week, the body of the last fallen hostage, Sergeant First Class Ran Gvili, was returned, meaning the command will now shift the nature of its work and effectively remain on standby for emergency operations only.

The command was formed under the leadership of the Special Operations Division of the Military Intelligence Directorate. It was staffed by regular-duty officers reassigned from their posts, alongside reservists and advisers, and included personnel from IDF units, intelligence branches and other bodies across the security establishment. Throughout the war, its mission was to function as a task-focused headquarters dedicated to protecting the hostages, clarifying their fate and securing their return.

Since the outbreak of the war, about 2,100 people served in the command, including roughly 1,300 reservists, about 800 Special Operations Division personnel and around 50 additional staff from various units. A significant portion of the manpower came from the Intelligence Research Division and Unit 8200, the IDF’s elite signals intelligence and cyber unit, which together accounted for about 60% of the reservists assigned to the command.

The initial assessment on the morning of the massacre estimated about 3,100 hostages and missing people, in part due to the large number of individuals cut off from communication. As events became clearer, the IDF determined that approximately 255 people were being held hostage in the Gaza Strip, including four who had been in captivity even before the war: Lt. Hadar Goldin and Staff Sgt. Oron Shaul, both soldiers killed in the 2014 Gaza war whose bodies were taken by Hamas, as well as civilians Avera Mengistu and Hisham al-Sayed.

As part of the command’s operations, 168 hostages were returned alive and the remains of 87 others were recovered during the war. Fifty-nine hostages were extracted in special operations, eight alive and 51 deceased. The command relied both on intelligence collected before the war and intelligence produced during it to locate the hostages and advance efforts to rescue them or secure their release.

Each hostage’s family was assigned a dedicated officer, who maintained continuous contact throughout the war. These officers provided intelligence updates and sought to create as much clarity as possible regarding the condition of loved ones held in captivity. All information that could be shared, subject to source protection, operational security and privacy considerations, was conveyed to families to help them understand the situation as fully as possible.

“From the beginning, we accompanied the families in order to mediate the intelligence information,” a security official said. “This was an important and complex event, and we invested heavily in it.”

'The numbers kept changing'

“The morning of October 7, I was off-duty and was urgently called up for the POW and MIA mission. Since then, I’ve been working on it continuously. I’ve commanded the unit within Military Intelligence since June 2024, under the leadership of Nitzan Alon,” said a senior security official involved in the Hostages and Missing Persons Command.

“The command was created because no existing body was equipped for a challenge of this scale. It wasn’t in any of the reference scenarios,” he said. “This command is highly unique, partly because it brings together personnel from a wide range of units: Military Intelligence, the Shin Bet, the Mossad and the Air Force—all under one umbrella. We realized this mission required the highest level of cooperation, including with the police and other security services.”

“Our first task was simply to understand what we were dealing with, who was abducted and who wasn’t. In the first week, reports listed 3,100 missing. Within two weeks, that number dropped to around 300. Only by December 2024 did we fully understand the fate of all of them—251 civilians, soldiers and foreign nationals were abducted on that day.

“Some were initially classified as hostages even when we weren’t certain, as part of an administrative decision. Further investigation concluded that some of them had never been kidnapped at all. We separated the living from the deceased early on, because each required a different operational approach. At the same time, we launched research to determine the hostages’ likely locations inside the Gaza Strip.”

For those believed to be alive, efforts were focused on forming the most accurate picture possible: where they were held and by whom, with an emphasis on minimizing the risk to their lives. These efforts were conducted jointly with Southern Command.

'The first is on board, second and third are with us’: footage from underbelly of helicopter during rescue of hostages Shlomi Ziv, Andrey Kozlov and Almog Meir Jan from the Gaza Strip

(Video: IDF)

“Unfortunately, we didn’t succeed in every case, and there were instances where hostages were harmed,” he acknowledged. “Each case was thoroughly investigated, and the lessons were fully integrated into our command structure and operational work. We also presented our findings to the families. We explained our mistakes and took responsibility. In my view, the lessons were internalized. But due to the complexity of this challenge, there were different kinds of errors—and yes, some hostages were hurt as a result.”

“Tracking live hostages is extremely dynamic, they were constantly moved, and our intelligence picture kept shifting,” he continued. “There’s never a moment where you can say, ‘We’ve found them, and they’re at this exact location.’ Our task was to maintain a constant ‘intelligence hold’ on them. That required cooperation with the Shin Bet and the integration of all intelligence disciplines—signals intelligence, human intelligence and interrogations of released hostages and captured terrorists.”

“There were countless dilemmas,” he said, “such as whether to eliminate an enemy combatant or refrain in order to preserve an intelligence window that might help us locate hostages. These decisions were coordinated with Southern Command and Military Intelligence. I don’t know of another war where you had to fight an enemy while hundreds of your own civilians were inside the combat zone and had to be protected.”

The official also described efforts to locate the bodies of hostages who had been killed. “First, we needed to confirm death with a level of certainty that could give families closure. Second, we carried out research to guide operational actions that could enable the return of the bodies. These missions carried lower operational risks, which is why we managed to conduct several successful recovery operations. Still, the research was incredibly complex because of the chaos on October 7. In many cases, Hamas didn’t know where the bodies were. In some instances, we knew more than they did.”

He gave a detailed account of Operation Brave Heart, which led to the recovery of Gvili’s body: “We acted urgently, and the research was conducted with great intensity. Operation Brave Heart required a special approach. After the last hostage return agreement, we continued investigating the locations of the remaining deceased. Ran’s case was especially difficult because neither Hamas nor Palestinian Islamic Jihad could say where he was at any point.

“We developed several possible scenarios and eventually concluded early on that he might have been buried in a cemetery along with other unidentified individuals. We were able to pinpoint that cemetery, and even the specific section within it that needed to be opened to identify him. This research was also conducted in coordination with the Shin Bet.”

“Fortunately, we found him in the estimated location and brought him home for burial in Israel. I didn’t think we’d reach that point,” he said. “Each success strengthened our sense that we were on the right track and that the other side had control over the locations of the bodies and was willing to return them.

“In hindsight, we now know that the cemetery direction was correct. At the time, though, it was only one of several investigative leads. That particular lead had existed for weeks, but it gained significant traction in the days leading up to the operation. Once political approval was granted, we moved forward.”

Unpublished operations and the toll of exposure

“The emotional and psychological strain inside the Hostages and Missing Persons Command has been immense,” the official said. “We’re talking about hundreds of personnel—more than half of them reservists—who live and breathe the hostage situation day and night. It’s with you at every moment. This is the reality of an active war: operations underway, exposure to traumatic material, mistakes that cost hostages their lives and an ongoing sense of urgency. Part of our responsibility now is to ensure these team members receive the support they need.”

Six hostages later executed by their Hamas captors mark the holiday of Hanukkah in an underground tunnel beneath Gaza

Running the command, he said, has been a collaborative effort with combat units, Southern Command and every branch of the intelligence community. “The Mossad played a major role in the negotiations and also in operational activities. The command separated the cases of living hostages from the deceased, and hostages were divided by geographic location. Each case became a ‘file’: If multiple hostages were held together, one team handled them; if it was a lone hostage, a dedicated team was assigned.”

According to the official, 38 hostages were killed in captivity under various circumstances from October 8, 2023, onward, while some were killed on October 7 itself. “Throughout the war, we never stopped planning operations,” he said. “It became more complex over time. There were missions that were never made public, some that were aborted at the last moment and others that were executed but failed because the hostage wasn’t at the expected location.”

He added that returning hostages were not subjected to formal interrogations but were gently interviewed. “We assembled a dedicated team of reservists whose sole mission was to conduct these debriefings.”

The official addressed two especially painful events: the accidental killing of three hostages—Alon Shamriz, Yotam Haim and Samer Talalka—in December 2023 by Israeli forces after they escaped their captors, and the murder of six hostages—Eden Yerushalmi, Ori Danino, Alex Lobanov, Carmel Gat, Almog Sarusi and Hersh Goldberg-Polin—by Hamas in a Rafah tunnel in late August 2024.

“These are extremely painful incidents with tragic outcomes,” he said. “Thorough investigations were conducted and presented to the families. From the first case, we learned a great deal about how to better brief our combat units to prepare for the possibility of hostages escaping captivity and moving within combat zones. The devastating event in Rafah, after which no more hostages were killed in captivity, taught us vital lessons about operating in environments where hostages may be held—and about understanding how captors behave under pressure when we don’t have precise intelligence about their location.”

He added that those lessons were later fully implemented in Operation Gideon’s Chariots in the later stages of the military campaign in Gaza.

What’s next for the Hostages and Missing Persons Command?

The Hostages and Missing Persons Command will now shift into emergency readiness mode, transitioning into a specialized contingency unit under the Special Operations Division. The command will remain available to support missions in other arenas and is placing new emphasis on mental health support for its personnel, many of whom were repeatedly exposed to disturbing content and traumatic situations during their service.

The unit is also conducting extensive internal reviews of its wartime operations, evaluating tactical decisions, coordination with non-military entities and how missions were carried out. After operating for nearly two years with a heavy reliance on reserve forces, the command is now engaged in restructuring its manpower model to align with ongoing operational needs.

“We thank the Hostages and Missing Persons Command for its significant contribution and its unwavering determination to gather every piece of information about the hostages and lead the efforts to bring them home," the Hostages and Missing Families Forum said in a statement following the announcement of the command’s closure.

“As with other agencies responsible for the events of October 7, the handling of the hostage issue—from day one until the return of the final captive—must be thoroughly investigated by an independent body. This includes clarifying the gap between the command’s official figure of 38 killed in captivity and the actual number, 46 hostages who were abducted on Oct. 7 and were either killed during their abduction or while in captivity.

“The families of the hostages, and the entire people of Israel, deeply appreciate and honor the security forces and all who contributed to the return of our brothers and sisters, some for rehabilitation, and others, heartbreakingly, for burial.”