The Israeli public is naturally focusing these days on one aspect of the agreement between Israel and Hamas: the return of the hostages still held by Hamas, which is expected to take place at the very start. But in fact, after the first phase many details of the agreement remain unresolved — and it seems only a clear American guarantee that the fighting will not resume allowed the process to begin without them.

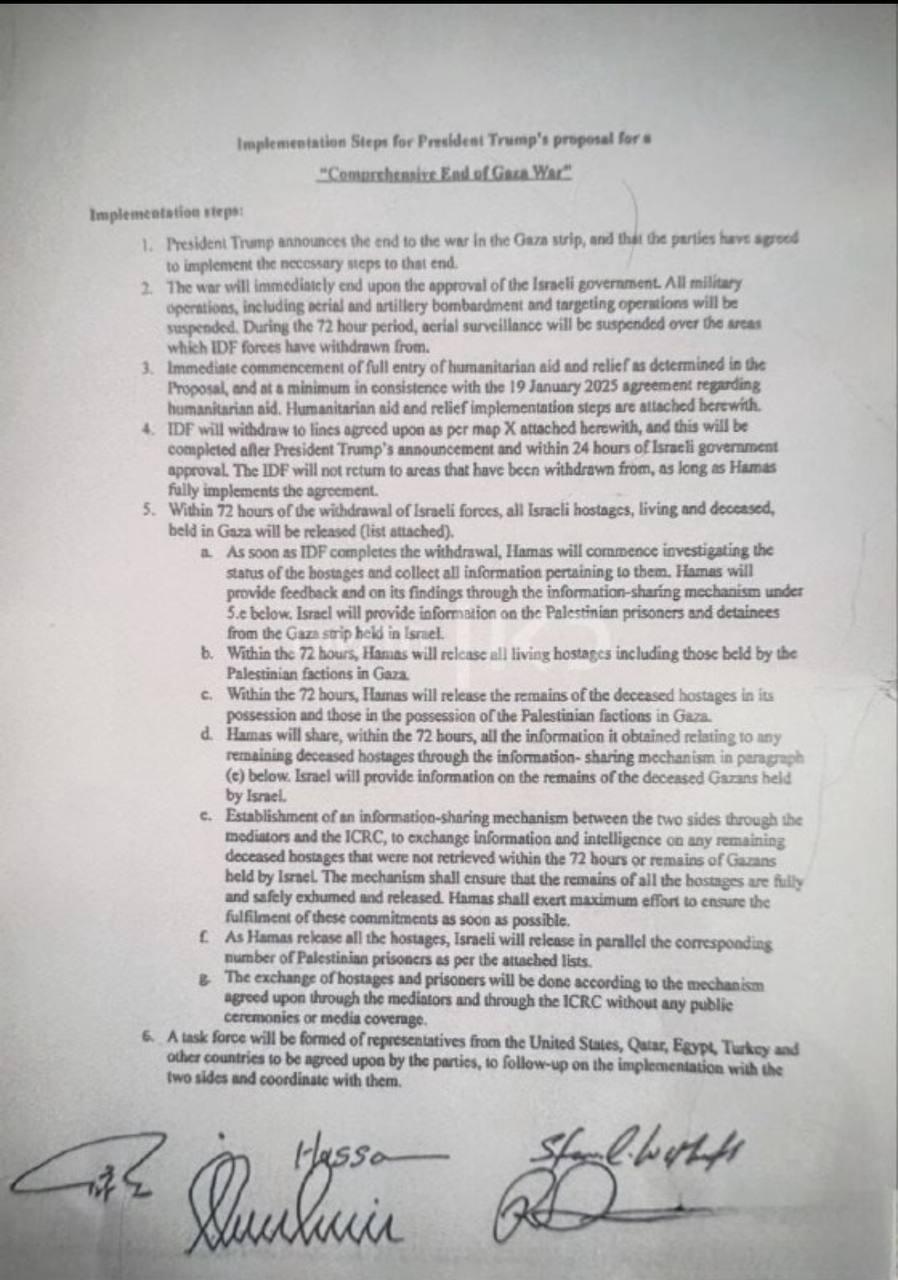

First, the issue of locating hostages who were killed: Because Hamas said it does not know the whereabouts of nine of the hostages, it was agreed to form an international force of Israel, the United States, Qatar, Egypt and Turkey which, with the assistance of the Red Cross, will try to search for at all the remains. That force is supposed to check information on the ground, search under rubble, send teams, take samples, and this may take many years. This mechanism still apparently needs to be formalized, as do the consequences of its actions. In Israel there are also fears that there are people whose burial places will never be found.

4 View gallery

IDF Chief of Staff Eyal Zamir in Gaza with troops on Friday

(Photo: IDF Spokesperson's Unit)

“Within 72 hours, Hamas will share all the information it has on deceased hostages via the information-sharing mechanism,” the agreement document states. “A mechanism for information sharing between the two sides through the mediators and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) will be established to exchange information on living hostages or killed hostages who remain, who have not been identified or returned. The mechanism will ensure that all bodies are identified and returned in full. Hamas will make its utmost effort to ensure completion of its commitments as quickly as possible.”

Then there is the security issue, and a big question mark around it: How do you ensure Hamas actually relinquishes its weapons? The mediators in the deal — chiefly Qatar, Turkey and Egypt — are supposed to be the ones to make sure the terrorist organization actually does so — but Israel must be involved to ensure Hamas is not cheating. The working assumption is that the terrorist organization will of course cheat, and will not give up all its weapons. It can, for example, hand over heavy weapons and perhaps some light weapons, but certainly will not give “the last rifle, the last pistol, the last grenades, the last RPG launchers,” and so on. This issue is not in the agreement document — and may be being left for the “day after.”

If Hamas is not fully disarmed, and given that it still enjoys popularity among many Palestinians, that means it will still have dramatic influence over governance in the Strip — and perhaps one day could stage a takeover again. The agreement will need to meet Israel’s security demands and ensure Hamas is removed from power mechanisms; otherwise — in that respect — it will be a failure.

The control mechanism in Gaza is actually another important unknown: U.S. President Donald Trump is supposed to set up the “Board of Peace” and appoint people to it, so far naming only former British prime minister Tony Blair. The president will need to appoint leaders from Muslim and Arab countries, perhaps members of the World Bank and the European Union, actors with money who can contribute to the Gaza reconstruction project. This council, headed by Blair, is supposed ultimately to take command over areas in Gaza and ensure Hamas is not present there, but this process is still in its infancy and its details have not been finalized.

4 View gallery

Destruction of Gaza City

(Photo: Samuel Grandos of Planet Labs, from The New York Times)

Alongside the council, there is also the pan-Arab force intended to be deployed in the Strip; there has been talk of Indonesia participating and sending troops alongside the United Arab Emirates and other states, possibly Saudi Arabia as well. This will have to be fully coordinated with Israel: how do those militaries enter and take responsibility for territory, under what rules of engagement do they operate, and how do they coordinate with the IDF so there are no exchanges of fire between the parties until the withdrawal is complete? This is an extremely sensitive event, so Trump will need to continue managing it — but it is unclear how far American commitment will go on this matter.

The IDF is remaining in Gaza at this stage, but will complete the withdrawal to the perimeter depending on the agreement’s progress. The details of the initial withdrawal in return for the hostages’ release have already been agreed, and it appears the IDF will stay outside city centers, but future withdrawals are supposed to be conditional on Hamas fulfilling its part of the agreement. And because the terrorist organization agreed to the deal only in light of clear American guarantees to Qatar and Turkey that Israel will not resume fire, it is unclear what will happen if gaps emerge between the parties later. What will happen, for example, if the Arab states declare that Hamas has been disarmed but Israel does not accept that finding?

Another major unresolved challenge is reconstruction of Gaza, where most buildings were almost completely destroyed: Trump talks about tens of billions of dollars to be poured into the Strip — funds that are also supposed to yield huge profits for investors, to make the project attractive. But how can it be ensured that, unlike before, the money will not go to Hamas and be used to build terror infrastructure?

In Gaza there are already many explosive devices scattered and many tunnels. In addition, during reconstruction — and since the “relocation” plan has been dropped — many Gazans will have nowhere to live at all, and will continue to live in tents for a long time, because much of the Strip is uninhabitable. The continuation of this situation could become a powder keg that could explode at any moment and destroy the entire arrangement. Therefore rebuilding these areas is an especially complex international task that needs to happen quickly and will require involvement from a number of countries — some of them even hostile to Israel.

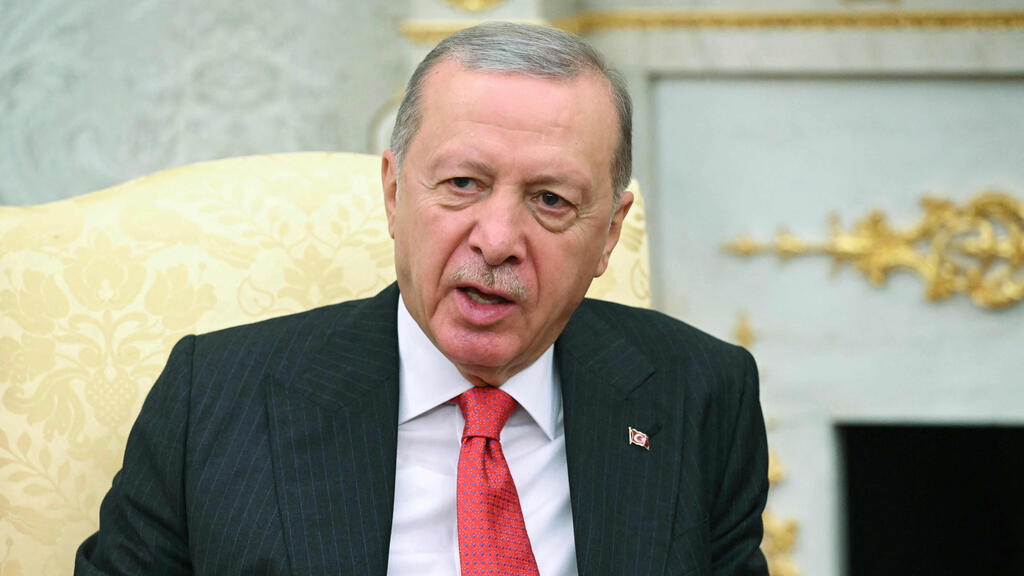

The economic interests in Gaza’s reconstruction are also a major unknown: among other things, the Trump family is involved, including son-in-law Jared Kushner, as well as the Erdogan family and the rulers of the Gulf states. In the administration a “Riviera” plan for Gaza has been circulating for some time, and Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich has claimed there are talks with Americans for Israel to receive a share, because Gaza could be a “real estate bonanza.” All this raises questions about the true aims of some of those involved in the arrangement, and whether Israel will be able to benefit economically from it in some way.

Another question arising from the agreement is Israel–Turkey relations, which have fallen to a new low since 7 October after a period of rapprochement. Now Turkey will be able to bring humanitarian aid into Gaza through Israel, and there is potential for reconciliation between the sides — since Ankara would need to set up a logistics hub in Ashdod to receive goods at the port and send them to Gaza. This would give Turkey a lot of leverage and create bargaining power vis-à-vis Israel, and it will likely also lead to lifting Turkey’s trade boycott and resuming Turkish Airlines flights.

A few weeks ago, Trump’s son Donald Trump Jr. met with Erdogan’s son-in-law, senior Turkish figure Berat Albayrak. The Turkish opposition alleged that in that meeting the two sealed a “deal” that would result in Turkey’s involvement in humanitarian aid and Gaza reconstruction, and in return “bring” Hamas to sign the agreement. If true, it is likely Turkey will expect compensation now.

And above all, probably, stands the issue of normalization — the same process Hamas tried to thwart with the 7 October attack, and which now could resume in full force. Indonesian President Prabowo Subianto’s speech at the UN General Assembly may have been a sign of things to come, but it is still unclear at what point Trump will kickstart the Abraham Accords again. It is also unclear whether Israel will be ready to do that in an election year, and how far it will go in promises of a Palestinian state as part of a deal that might be signed, for example, with Saudi Arabia.