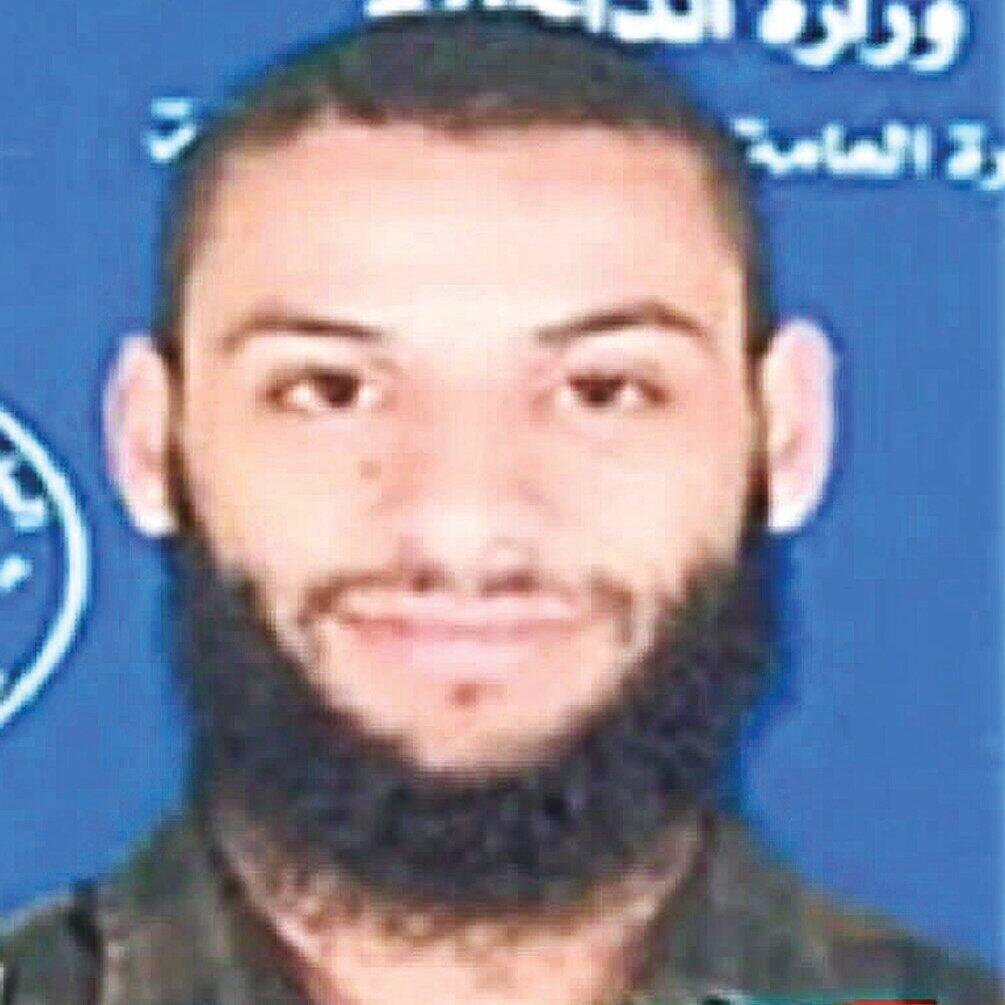

The video quickly became, on that same Black Saturday, one of the defining symbols of the horrors of October 7. Avinatan Or and Noa Argamani were seen terrified at the moment they were separated; Argamani, on a motorcycle, reaching out toward Or, who was being marched away, bruised, surrounded by gunmen intoxicated with success. One of them, seen in the footage pushing Or and pulling him away from his loved one, would soon be identified as Ahmed Shaer.

He did not know it in real time, but Shaer and his fellow abductors became the target of a small unit within Military Intelligence, which was given one of the most complex missions of the war: to locate all the abductors, murderers, rapists, looters and arsonists who crossed into Israel on October 7 and neutralize them. They operate in absolute secrecy from a small room at Southern Command, under the name NILI, an acronym taken from the biblical verse “The Eternal One of Israel will not lie,” perhaps a hint that none of these terrorists would be forgotten. Not even Shaer.

The problem was that he seemed to know it and tried to stay under the radar. “He was extremely cautious,” said Capt. A., commander of NILI, whose members are speaking for the first time in an exclusive interview with 7 Days, Yedioth Ahronoth’s weekend magazine. “Shaer almost never left the house or spoke with people. For a long time we did not even know where his home was. He left no trace.”

But about a year ago, that changed. Capt. A. received the long-awaited call indicating Shaer’s estimated location and began feeding intelligence into a file that would make it possible to build a case for his neutralization, or in intelligence parlance, his “incrimination.” Working alongside him was Sgt. S., an intelligence analyst trained to track down terrorists and operatives in hiding.

“The work was relatively long,” S. recalled, “both in incriminating him and tying him to the event, and in narrowing down and locating his whereabouts. It was a lengthy process that took about 10 months.”

Eventually, Capt. A. and Sgt. S. focused on several buildings in Gaza, one of which, according to their research, was where Shaer was hiding. “We debated between them,” Capt. A. said. “In the end, S. managed to link him to one specific building and then to a room where we knew he slept. We prepared in the middle of the night to catch him while he was asleep.”

The operation was set for March 25 of this year. Toward evening, Capt. A. and Sgt. S. arrived at the strike cell, a room serving as a command center where representatives from the Air Force, intelligence and operations staff are physically present or dial in by phone.

“Everyone arrives,” Capt. A. recalled. “We drank coffee, because we knew how the night would begin but not how it would end. You are constantly imagining how the target you worked on for so many months will no longer exist by morning. I finish my coffee, put on my headset and everyone joins me on a conference call. S. and I are on, along with Southern Command intelligence, the task force commander who coordinates the fire, and on the line as well are the Shin Bet internal security service and the Air Force.

“This is work done quietly and with extreme professionalism. There is no shouting in the room. S. and I have two minutes on the clock to give them the entire intelligence picture. We have been on him for 10 months, but at that moment you have to deliver the most focused, precise and rapid information possible, information that can assist the strike: what the house looks like, what the walls are made of, when the target goes to sleep. At that moment, my role as the intelligence officer is to say whether the intelligence picture has changed. I have to verify that the target is still there.”

And then?

“At a certain point I said, ‘Incriminated.’ The task force commander declared, ‘Authorized,’ and the Air Force representative said over the radio, ‘Released.’ Then there is half a minute of silence, with everyone tense, waiting to see whether we hit the target. It is an emotional, nerve-racking moment, when months of work, including images, videos and everything we heard about Avinatan and Noa, all converge into those 30 seconds of silence, as everything you know about Avinatan and Noa runs through your mind.

“Then you see an explosion, and the missile goes through the window that S. managed to tie to him. There are a few seconds of smoke, and we see people running out of the building. These are super-critical moments in the context of such a boutique strike: We do not know who the people fleeing are, and from there, serious work begins to understand whether we succeeded or not.”

“That night,” Sgt. S. said, “I was only hoping to find out that he was dead. It is tension like nothing else in the world. My baby, the thing I worked on more than anything, was distilled into one very significant half-minute. When they finally said ‘Alpha’” — the radio code name indicating the missile had hit — “I was happy that at least the operational part had been carried out successfully.”

But you did not know whether your target had been neutralized.

“I can say that it really confused us that so many people fled the building,” Sgt. S. said. “For a full week I was grinding my teeth, searching for the indication that he was dead. On Telegram and in all kinds of other places. So many people, in every field, were running every possible check.”

“No matter how long we have been awake,” Capt. A. said, “after a strike like that there is no chance of falling asleep. We are sitting in bed with the phone, searching for every scrap of information. There are, for example, Gaza journalists who publish lists of the dead. Every message in Arabic gets run through Google Translate, and you struggle to fall asleep.”

So how did you ultimately understand that you had succeeded, that Shaer had been neutralized?

Sgt. S.: “After a week we received a positive indication that he had been killed. Quite simply, people began posting eulogies for him. He was apparently wounded and fought for his life, which is why we received the confirmation later. At the time this happened, Noa was already back in Israel and Avinatan was still in captivity, so there was sensitivity around publication.

"It was emotional and a kind of closure, because I was personally connected to their story. Already on the night the bomb was dropped, I imagined the announcement that would come out and their sigh of relief. It was delayed, but it happened. There was nothing more moving for me than seeing that they came home and were reunited. For me, that is closure: seeing that he returned and learned that most of the people who abducted him are no longer here.”

It began about a month and a half after the war broke out. Capt. A. was summoned to the office of his commander, the head of the targets branch in Southern Command intelligence, the unit responsible for the command’s target bank. The meeting took place against the backdrop of intelligence received from the Shin Bet concerning Col. Asaf Hamami, commander of the Southern Brigade in the Gaza Division, the most senior military officer killed on October 7 and abducted into Gaza.

“They told me, ‘We want you to set up a team that will deal with everything connected to the hostage cases, starting from one test case, Hamami,’” Capt. A. said. “At the Shin Bet, they worked hard and surfaced all kinds of intelligence about the abduction, but in the end they do not have a strike capability. They needed someone from the military to be the operational tip of the spear.

“Based on the information we received, we began tracking the targets connected to the abduction. Along the way we discovered that a friend of the person we were focusing on had also crossed into Israel on October 7. We said, ‘Let’s do something about him as well.’ Slowly, more targets emerged, and as hostages returned” — bringing additional intelligence — “the circle expanded with more names of people who abducted, murdered or guarded captives alive." The list eventually included even those who pulled captives from vehicles and took part in the release ceremonies, he said, “and in general, anyone who did bad things to them.”

Very quickly, the number of targets compiled by NILI reached about 6,000 terrorists, but today the figure is higher and includes everyone who entered Israeli territory on October 7, as well as additional targets, such as the terrorists who held hostages in captivity. Still, priority is given to those among them who carried out murders and abductions.

“We prioritize targets that represent closure for the families, because that is our obligation to the public,” Capt. A. said. “If there is a specific terrorist linked to a murder case, he is ranked higher for us than someone I can say only that he crossed into Israel.”

The assessment is that more than 1,000 of the October 7 infiltrators have already been killed. Among them: the terrorist from Mefalsim who boasted in a phone call to his father that he had murdered 10 Israelis; the “journalist” who reported on the assault from the lawn of Kibbutz Be’eri; the abductors of Eitan Mor; the abductors of Noa Argamani and Avinatan Or; the terrorist who breached the border fence with a bulldozer in the widely circulated footage; and many others.

NILI builds a detailed file for each of these terrorists: who he is, what he did, what is known about his life, his associates, his daily routine, where he lives or hides and countless other details. The ultimate goal is that when an operational opportunity arises, that target will be neutralized.

One of those targets was Wael Matria, a platoon commander who infiltrated the Nahal Oz base on October 7 and, together with another platoon commander, was involved in the abduction of surveillance soldiers Karina Ariev and Liri Albag. Capt. A. assigned the task to his most senior investigator, Sgt. G.

At the time, he recalled, G. did not say a word about the fact that she knew Albag from school. Her heightened motivation to track down Wael seemed to him natural and routine. “She was obsessive and searched for him relentlessly,” A. said.

What did the pursuit look like?

Maj. A.: “Matria and his accomplice were two targets we worked on intensively together with the Shin Bet. We tried to strike them many times, and each time something happened and it did not go through. A kind of bad luck. I remember that every phone call would send us jumping, and we would say, ‘This time it’s happening.’

“One day I came in for what was supposed to be another routine day at the office, and that night the first ceasefire was due to begin, which only heightened the drama. We understood that we were about to enter a different phase and did not know when the next opportunity to neutralize that terrorist would come.

“In the evening, I get a call from the Shin Bet: ‘We think our target is on such-and-such a street.’ I sprint to the strike cell, ask that surveillance be positioned on the street, and start scanning. These are extremely stressful moments. That’s why it’s critical to be laser-focused, to connect the intelligence to us in real time and not lose it. It means pulling in people you don’t know, who suddenly become your strike team, and everything goes from zero to 100, because in two minutes a lot can happen.”

And then what?

“We begin scanning and trying to locate the target at the spot the Shin Bet pointed to, until we understand that we are locked on. Then the intelligence officer says, ‘Incriminated,’ and the task force commander says, ‘Authorized.’ In this case, the target was walking down the street, and it was 30 tense seconds, when in the final five seconds the target decided to stop at an intersection — and that is where he was neutralized, together with his accomplice. It was an operational opportunity once we realized the two of them were together.”

How many targets like this does each investigator handle at the same time?

“Each one is responsible for about 20 targets simultaneously. Any piece of information connected to them comes to the investigator, and she processes it, sometimes on a daily basis. When they ‘break down’ a target, all kinds of details surface: who he wakes up with in the morning, where he goes, where he works, where he sleeps, his daily routine. Numbers, photos, videos, lists — these are not things that are handed to us on a silver platter. Every video that comes out on Telegram or elsewhere, we try to cross-check in our systems.

“Another task of the cell is to determine who is alive, who is dead, who is detained, who infiltrated Israel. In my view, that is a task that will accompany us for years to come, because we are constantly receiving new information about people who entered the country and we did not know about at the time.”

The intelligence on the targets flows to NILI from a wide range of sources: debriefings of hostages who have returned to Israel; interrogations of terrorists by the Shin Bet and Unit 504, the IDF’s human intelligence unit; intercepts from Unit 8200, the military’s signals intelligence arm; documents and computers seized in Gaza by Amshat, the unit responsible for collecting intelligence materials and technical spoils; and, of course, open-source intelligence and videos the terrorists themselves recorded.

The investigators can request specific information from any of these units — for example, asking a Unit 504 interrogator to question a particular terrorist about a friend of his who is a NILI target.

How does this actually work? Give an example.

Sgt. G.: “For example, I scroll on TikTok and download a video, say, of an attack on one of the kibbutzim. You see people’s faces there. At that stage they are still anonymous to me, so I upload the footage into facial recognition software, similar to biometric systems. If a name comes up, I cross-check it against a lot of other information. It may be that the operative is already on certain lists, and that provides additional corroboration” — meaning cross-verified intelligence indicating it is the same person and that he did in fact carry out what is attributed to him.

So you figured out his name and what he did. What comes next?

“We try to understand who the person is: where he lives, what car he drives, where he works, what he likes to buy at the market, at what hours he goes there. It really gets down to the smallest details — whether he talks to his wife, how he talks to his wife, whether he has another wife. By the way, almost all of them do, and their wives probably know and stay silent; it seems to be more accepted there. Sometimes we focus on the people around him — catching him through those who surround him, through family, through a family friend, children.”

Sgt. S.: “We truly know the targets from A to Z. We can say what they like to do, what they like to eat, at the most tactical, granular levels. There are some who wander around all day, strolling freely through the streets of Gaza and behaving as if they did nothing. Others continue to deal with military activity and plan attacks against the forces.”

This stage — building the case and gathering the material for a terrorist’s file — can take weeks, months, sometimes even years. “There was a target I started working on in November 2024 and only this month managed to incriminate him, and there are targets I can incriminate within two days,” Sgt. G. said. “It varies from operative to operative and depends on how cautious he is, on his counterintelligence awareness. Over time I noticed that many of the October 7 videos began disappearing from Telegram. They understood the mistake they made in publishing those videos in the first place, and that also makes things harder.”

So what do you do?

“You keep investigating. It’s something that occupies you even outside work hours. You go back to sleep and think of more ways to find the person — when he goes to pray, where. In the end, it’s the most intimate familiarity there is. You live him 24/7, really connected to him, especially given that before this you did not even know who he was. We know these operatives better than they know themselves.”

But if he goes to the mosque every morning, isn’t every morning a good time to strike?

“In principle, yes,” Maj. A. said, “but we have to be 100 percent certain. We are not operating on routine activity, as in, if he’s there every morning then let’s strike. I need to know, with a very high level of confidence, that my operative is at the location at the moment I say ‘incriminated.’

“At the end of the day, these people who infiltrated Israel on October 7 and then returned to their routines spend some of their time engaged in terrorism and continuing to advance attack plans. Some of the time they go to the supermarket or go to a school and hide there. If I can prove that everyone around them is an operative, there is no problem — I can strike. But if I have incriminated a mosque, and I know there are 20 people inside, and I cannot say with absolute certainty that they are terrorists, then we wait for him to leave the mosque.”

“We try to incriminate our operatives at their ‘anchors’” — basic locations where the terrorists routinely stay — “places we know they use,” said Sgt. Y., an intelligence analyst in the unit. “For example, where they sleep. I know he will be there all night, that he will not leave for even a minute. And if we know to say that he is about to leave, then we say that.”

“It’s like a puzzle, where everyone assembles their own piece,” Sgt. S. said. “HUMINT” — human intelligence — “SIGINT” — signals intelligence, mainly communications — “and VISINT” — visual intelligence, such as aerial imagery and drone footage. It all comes together into one complete operation.”

To complete the puzzle, analysts from the decoding cell come into the picture. That team, also part of the targets branch, works in close coordination with NILI. They are the ones who ultimately pinpoint the terrorist’s location.

“I can ask Military Intelligence for a ‘tool’” — usually a drone — “and follow the operative,” Capt. A. said. “Every place he enters, I ‘stab’ a point on a virtual screen” — marking the location. “Slowly, I start assembling a kind of puzzle. Then I go to the Shin Bet and say, ‘I’d appreciate it if you activate one of your investigators from Gaza who knows the area and understands it. Tell me what the points I marked are.’ He’ll tell me, ‘That’s a supermarket,’ ‘That’s a garage.’

“Later I notice that these points keep repeating themselves, and I begin to understand the hours and daily routine of the operative.”

At that point, Sgt. 1st Class B., from the decoding branch, enters the picture. “For example, I tell him,” Capt. A. said, “‘I saw my target enter a building and disappear.’ I don’t know what happens inside. B. knows how to look at a building and see that, for instance, there is a narrow shaft running across several floors — probably a stairwell — so the terrorist is certainly not sleeping there.

“Then, for example, a report comes in that he spoke with a friend and told him, ‘I’m by a window, freezing.’ From that I know there is a window. I go back to B. and ask, ‘Where are there windows in this building?’ He answers and narrows it down. Then, say, I hear that the room has white bars, and B. tells me that only three of all the rooms with bars have white bars. And that’s how we narrow it down all the way, until we have his precise location.”

Quite a puzzle. And what if there is no such information?

“Sometimes I have an intelligence item that isn’t geographic,” Capt. A. said. “For example, a terrorist’s home is bombed, and we understand he wants to move elsewhere. In that case, B. has nothing to tell me — he doesn’t predict the future and doesn’t know where the operative will go. Here I need a Military Intelligence body that can tell me where people usually relocate in situations like that.”

That was the case, for example, with Mahmoud Afana. On October 7, Afana was one of the terrorists who infiltrated Kibbutz Mefalsim, and his chilling boastful phone call to his father became infamous.

“I’m inside Mefalsim. Dad, I killed 10!” he said proudly. “Their blood is on my hands. I’m talking to you from a Jewish woman’s phone. I killed her and her husband.” His excited parents congratulated him on the “achievement.”

“This is a person we worked very hard to locate together with many different bodies,” Capt. A. said. “From someone who boasted and became a hero, he turned into a mouse in a hole, fleeing from place to place. The moment his call was published on October 8, he understood he was wanted.

“Then he began implementing all kinds of counterintelligence procedures: He doesn’t move around crowded places, doesn’t use any technological means whatsoever. He lives alone, stays alone, tries to manage on his own. He surrounds himself with no one and trusts no one.”

So how do you reach a terrorist like that?

“The secret to neutralizing a person like this is patience and a very strong belief in the process,” Capt. A. said. “There is a lot of frustration in trying to find someone like that, because by the time you finally connect to the smallest clue, he is already gone — and that happens a lot. We searched for him for two years. The change in the operational reality in the Strip, with maneuvering taking place in different areas each time, caused many operatives to move around. And when that happens, I know how to latch onto it.”

In early September of this year, just under two years after his phone call from Mefalsim to his parents, Afana was neutralized.

One Saturday last summer, all NILI soldiers, a single-digit number — who were home for the weekend were called back in, and those who were on duty at the base were instructed to drop whatever missions they were working on.

“They told us, ‘Leave everything you’re doing. This is what we’re dealing with now,’” Sgt. G. said. “It was at such a level that they couldn’t even wait until Sunday, when everyone would be back from home, to start working on it.”

The target was connected to one of the hostages who had been returned. “Each one of us,” G. said, “incriminated someone connected to that hostage — whether it was an abductor, someone who held him, or someone who moved him from place to place.”

And what suddenly happened that Saturday?

“After we had incriminated the target, an intelligence indication came in that the person was located. We saw him from an aerial platform tracking him, moving around in a very restless way in an area with many tents, a place with a great many people. And we waited for the right moment to pull the trigger.”

What was the right moment?

“When he simply separated from a very large group of people he had been with and went to a restroom. That’s when we understood he was alone — and that’s where we struck him. We waited about an hour over the target, when we knew we could say he was there, in order to reach the right time and the right place, when he was not moving, when he was static, with a minimum number of people around him.”

Sgt. S.: “It really creates an extraordinary sense of closure for the hostage and his family. It’s the small seal the army and the state can give a person, to say: ‘We see you,’ ‘We care about you,’ ‘We are committed to telling your story and making sure the account is settled.’”

Not all targeted killings are publicized when they occur, and in cases involving living hostages, members of NILI sometimes began working on the target only after the hostage returned. That was the case with Eitan Mor. The man who abducted him was neutralized, but publication of the strike was permitted only after Mor returned to Israel in the most recent deal.

“After the strike was made public,” Sgt. G. recalled, “Eitan posted a story with a photo of the abductor and a cynical line about fate. I felt he was sending us a message of thanks. Knowing that I gave a sense of relief to someone who went through a nightmare, because we neutralized his abductor — for me, that’s wow.”

“When hostages return, they shed light for us on the meaning of the work,” Sgt. S. said. “You see a hostage in a video, but you can’t really understand what the person experienced in those moments. When a hostage comes back and knows that his captor or abductor is no longer alive, knowing that I was the one who closed that circle for him, even in the smallest way — that is what moves me most.”

“I remember that during the period when I was dealing with the person who abducted Eitan Mor, we visited the Nova site,” Capt. A. said, referring to the site of the music festival massacre. “You walk among the small memorials, you see a picture of Eitan Mor, you see Avinatan Or, and you say, ‘I dealt with the person who abducted him.’ And then another picture, and another. It fills you with an immense sense of meaning and mission.”

One weekend, Capt. A., a Hapoel Tel Aviv soccer fan, allowed himself to go to a match to clear his head. He reached the stands and, one row below him, spotted a familiar face. It was Liam Or, the hostage who returned in the first deal. “We worked very hard in the cell to find two people we could say with certainty abducted and held him, and in the end we struck them as well,” he said. “Time passed, we were already dealing with other things, and one day I come to a game and Liam is sitting one row below me. I see him and know that, well, we neutralized those connected to him.

“At that time, those terrorists had been holding other hostages, and there was a risk in revealing that we had carried out the strike, so it wasn’t something that was published. And I’m sitting near a hostage who, a moment earlier, had been in captivity, and I have this enormous internal dilemma: Does he deserve to know that we neutralized the people who abducted him, or not?

“On the one hand, there is an element of closure, and that’s what I work for, and he deserves to know. On the other hand, who am I to, in the middle of a Hapoel game, drag him back into the trauma of captivity? And I don’t know how he would react to that.”

What did you decide?

“Not to say anything. Even the smallest risk of dragging him back into something he did not want to relive was too much. Each of us went our own way, even though inside I was bursting. Only months later was it published. The publication, by the way, is our tool for conveying the message to the families, because we do not speak with them directly and do not even know whether they are aware of NILI’s existence.”

“It is always published as ‘the IDF struck’ or ‘the IDF neutralized,’” Sgt. S. said, “and I think that is the right way to do it. In the end, I see myself as the one who built the case, but behind me are many units — in intelligence, the Air Force. Ultimately, it is a huge enterprise.”

Some of the footage the unit’s members are exposed to in their daily work is extremely difficult to watch. Capt. A. said he tried to limit his investigators’ exposure as much as possible. “Things that are hard on the soul, I tried to watch myself,” he said. “To extract names and then let them work on the names. It’s important to say that for every target, we work with corroboration that he infiltrated, murdered, abducted and so on. The terrorists were equipped with GoPro cameras, which were left behind in Israel on the bodies of dead terrorists.

“Y., for example, worked on a particular abductor whose kidnapping videos were very hard to watch. I told her, ‘You work on him — the corroboration is on me.’ The women here are fighters in their own way. There are fighters in the field, and there are fighters sitting in front of a computer, exposed to extremely difficult material on a psychological level. But that is also what makes us understand every day why we do what we do.

“There is nothing more satisfying than neutralizing that abductor and then going for a run at the Tel Aviv Port, seeing the sign calling for the hostage’s return, and saying to myself: ‘I was responsible for making sure something like this will not be done again by people like that.’”

The word “revenge” never comes up in our conversation, nor is it part of their lexicon. When asked, they are clear that this is not what motivates their work. So what does? Closure for the families — and a genuine security necessity.

“In the end,” Sgt. S. explained, “all 6,000 of those targets — from the terrorist who crossed the border in flip-flops to the company commander who led an entire unit — are people with tactical experience and real knowledge of what the country looks like, how it operates, what the terrain is like, where there are gates, how the kibbutzim are built. They can lead the next massacre, and in my view that is the meaning of eliminating them.

“Some of them receive honorary ranks for having infiltrated Israel and murdered people. What we see is that, little by little, they are climbing the command ladders. They are always trying to continue carrying out these activities. It did not end on October 7. On the contrary, it generated motivation for others to do the same, because it showed that it was possible.”

“These people,” Capt. A. said, “also have an insane fan base. They are surrounded by people who idolize them, and if one day Hamas is gone, they might establish the next movement, because they are a symbol of this idea. Beyond that, they have accumulated a great deal of operational experience. They breached a fence, overran a community, know how to read maps, and have experience killing soldiers and murdering children and anyone else who stood in their way. They are dangerous people, and they are the ones who will lead the next infiltration.”

Which targets matter most to you personally?

Sgt. G.: “An operative who infiltrated the Nahal Oz post, beheaded a soldier and committed atrocities against soldiers.”

Sgt. Y.: “An operative who infiltrated the Gaza Division and carried out murders at the base. In the end, I myself can’t decide what is more ‘valuable’ — killing an operative who murdered, or one who abducted or raped. I work on all of them in parallel. All of them matter. I don’t prioritize someone who murdered or raped over someone else of that kind. I do prioritize them over someone who, say, stole weapons. But ultimately, for me, they are all evil.”

Sgt. S.: “I have my top five — targets that are extremely hard for me to find. There was one evening when I told myself: a ceasefire is about to start, and I have to finish this now, because if not now, I probably never will. I stayed until very late, reached some really good intelligence insights around 10 p.m. at the office, and I succeeded. There are times when I tell myself: this is my moment — to give 200 percent. That was one of those nights.”

Indeed, one of the cell’s current challenges is that now, during the ceasefire — and possibly afterward — there are no strikes. “From a reality in which we could strike the moment we received an indication,” Capt. A. said, “we are now only maintaining targets: knowing how to point to as many operatives as possible, as many locations as possible. The moment there is a violation, or a response on our part, we will take the information from that bank, find who we need and strike.

“We’re not taking our foot off the gas. Now we have quiet and time to try to locate as many of these people as possible. We will reach all of them. Our work never ends. We are temporary here and one day we’ll be discharged, but others will come after us. What will remain is the promise that we will always pursue and always try to find anyone who dared set foot across the border. The mission will be completed.”

What happens after a target is neutralized?

Sgt. G.: “Each of us has an organized Excel sheet with the targets she’s working on. Everyone chooses what to do once they’ve been neutralized or incriminated, or once you’ve finished working on them. I personally mark those in a green column.”

Sgt. Y.: “I mark them in red.”

Sgt. S.: “And I have a separate table under the heading ‘Neutralized.’”