The adage “God and the devil are in the details” generally holds true when it comes to aerial weapon procurement deals in the modern era, and is especially true when it concerns Saudi Arabia’s intention to purchase F‑35 jets from the United States and the readiness of the Donald Trump administration to oblige.

Not only politicians and defense officials in Israel are expressing concern about this deal and questioning whether normalization with the kingdom will compensate for the damage to what is defined as Israel’s “qualitative military edge.” Intelligence agencies and the Pentagon are also skeptical about the deal out of fear that knowledge of the aircraft’s capabilities and features (generation 5, the most advanced as of now) might leak to China, which has trade and cooperation agreements with Saudi Arabia.

6 View gallery

F‑35 jet and Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman

(Photos: Nathan Howard/AP, Jana Rodenbusch/Reuters)

But when you dive into the details of the proposed deal, especially the features and capabilities of the F‑35 that the U.S. supposedly intends to include, you understand that the devil is perhaps not that terrible. Israel inherently has the ability to influence what the Saudis will receive, so it’s premature to panic — if such panic is even necessary. Even if the deal goes ahead soon (the first jets will be supplied only in about six years), the benefits that Israel will derive almost immediately from normalization of ties with Saudi Arabia justify taking a calculated risk.

On the face of it, there is reason to fear the plausible scenario in which the royal house changes its policy toward Israel, an upheaval that would bring extremist Islamist elements to power. In that case, if Saudi Arabia were to have 45 F‑35s, as it is requesting, Israel would be forced into prolonged and expensive high alert, since its air‑defense systems would find it harder than ever to detect and intercept the stealth fighters that would launch from airfields in north‑western Saudi Arabia, only about 5 minutes flying time from Israel.

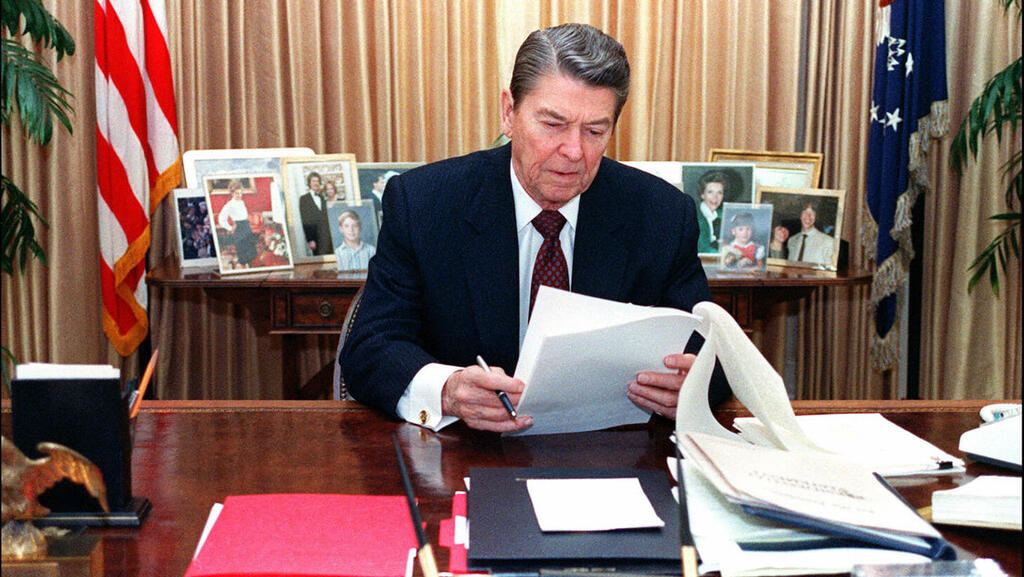

6 View gallery

Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman meets with US President Donald Trump in 2018

(Photo: AFP)

For example, F‑35s taking off from the military airfield on the Red Sea coast need not penetrate Israel’s air‑defense arrays at all. They would be able to launch precision glide bombs and U.S. air‑to‑surface missiles — whose ranges exceed 100 km.

Moreover: the advanced radars and other autonomous capabilities of the F‑35 turn these aircraft into flying systems of warning, intelligence collection, command and control, and interception. Through them, the Saudis could monitor every movement of Israeli aircraft, UAVs and cruise missiles, not only in the Red Sea arena but from the north and northeast of Israel. This would significantly reduce the Israeli Air Force’s ability to gather intelligence and strike with concealment and surprise across the Middle East, for instance in Iran, the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean.

And all this is before one addresses the exposure of the Saudis to technologies, as well as to operational and aerial attack techniques, which might migrate not only to China and Turkey, which have trade and cooperation agreements with Saudi Arabia, but also to other nations that spy on it, chief among them Iran.

The non‑secret switch

But — and here is a big “but” — the F‑35 the U.S. will sell to Saudi Arabia will likely differ in many details and important capabilities from those in Israel’s “Adir” model. Even if Saudi Arabia receives the latest model of the fighter jet (Block 4), it will not include the improvements, avionics and electronics that Israel has installed.

For example, unique, long‑range and extremely precise munitions that, according to foreign reports, were developed or adapted for the Adir by Israeli defense industries. Or conformal fuel tanks, which, according to foreign reporting, were installed onboard to allow the jet to extend its flight range without air‑refueling by about 30 % (depending on how much weaponry it carries) and hit targets in Iran.

6 View gallery

Three new Adir (F-35i) aircraft land at Israel's Nevatim base in March

(Photo: IDF Spokesperson's Unit)

In addition, Israel’s defense industries have inserted electronic warfare systems, intelligence‑gathering capabilities and encrypted sharing with other aircraft and UAVs, some of which do not exist in the American F‑35s (or if they do, they are in an export version which does not include the features in the Israeli Air Force or U.S. Navy variants).

But Israel’s main qualitative advantage lies in the fact that the Air Force knows the aircraft and its radar signature very well across different flight profiles, and thus knows its weaknesses. It can exploit them if required. During the war, the operational methods of the F‑35 in defense and strike were tested and improved, and so too were maintenance procedures refined. Israel is the only country in the world that maintains its F‑35s comprehensively, even under fire.

And finally, if Saudi Arabia does flip and becomes a hostile actor, Israel would retain the capability to destroy those aircraft on the ground before they are used against it — provided, of course, it is alert and not bound up in complacent assumptions.

It is also worth recalling the technological and operational restrictions American manufacturers embedded in the aircraft at the Pentagon’s request. When the F‑35 project began, due to the enormous costs, it was planned as a multinational scheme in which many states that are not NATO members would participate. The Americans feared that the new technologies and avionics installed in the jet might leak to undesired actors and enable unstable states — especially in the Middle East — to use the jet contrary to U.S. interests and against friendly countries.

To keep the operators dependent, the U.S. did several things. First, it itself controls the maintenance of the jets. Beyond that, the Americans included in the operating software switches and codes that allow the Pentagon to monitor at any time how and against what target the partners to the project intend to use the jet; for example, if its change of route signals intent to strike a target of interest to the U.S. These systems and the sale‑contract restrictions allow Washington to disable the F‑35 via so‑called “kill switches” (software‑coded shutdown switches).

For these reasons (and also due to the jet’s high price) the United Arab Emirates told the Americans in 2021 “no thanks,” foregoing the F‑35s that Trump agreed to sell them after they joined the Abraham Accords and normalized relations with Israel.

Israel, in contrast — after a long and bitter struggle that delayed the arrival of the first jets in Israel — is exempt from most of the above restrictions. It can introduce upgrades and improvements as it wishes in many of the systems that give the Adir (F‑35i) its qualitative superiority over other operators of the jet.

What we learned from the Reagan administration

Every year that Israel operates the Adir the gap in qualitative‑operational terms over other states that hold the jet widens. Therefore, it’s not only important which model of F‑35F the Saudis will buy and with what avionics, but also which munitions will be sold to them with the jet and which limitations will be placed on them. For example, a ban on deploying them at airfields in western Saudi Arabia, from where they could attack Israel unexpectedly.

In the 1980s, a confrontation took place between Israel and the administration of President Ronald Reagan, when the U.S. sold Saudi Arabia early‑warning / command & control aircraft of the AWACS E‑3 type (Boeing 707 platform with a giant radar “mushroom” antenna). Israel and AIPAC’s lobby opposed the deal, which also included three tanker aircraft, on the grounds that it would irreversibly damage its qualitative military edge. Supporters of Israel from both parties (yes, there were days when support for Israel was bipartisan) even enacted the Qualitative Military Edge law, which limits U.S. arms sales to actors that endanger America’s friends.

In the end the confrontation tapered off. Reagan did sell the jets to Saudi Arabia, but their operators remained American for many years and Israel received compensation in the form of F‑16s. The same pattern held when the U.S. later decided to sell F‑15Es to Saudi Arabia. There was a big outcry which dissipated when it became clear the Americans held the switches and the Saudis couldn’t do as they wished.

The conclusion is that normalization with Saudi Arabia is worth the moderate risk inherent in the sale of F‑35 jets to the kingdom, provided the standards and restrictions placed on the deal by the U.S. are respected.