The Knesset’s National Security Committee met this week to advance a bill mandating the death penalty for terrorists. The legislation was pushed aggressively by National Security Minister Itamar Ben-Gvir and his far-right Otzma Yehudit faction, despite warnings from military and legal officials that the timing is reckless and the law itself unworkable. Even parliamentary legal advisers called the vote invalid, but the committee went ahead anyway.

The very fact that this debate took place at all is symptomatic of what has defined Ben-Gvir’s tenure in government: a steady stream of provocative, media-driven stunts designed to posture as “tough on terror.” In practice, these gambits have not offered real solutions to Israel’s security challenges or social divisions. Instead, they have left the country less safe, more isolated internationally, and more polarized at home.

At its core, the idea of executing convicted terrorists is not a deterrent; it is a recruiting gift. For decades, terrorist movements have sanctified “martyrs.” They glorify death in service of their cause. Executing them does not erase their deeds—it amplifies them. Each death at the hand of the state becomes a rallying cry for new recruits, a reason to avenge, a symbol around which to organize more violence.

Terrorists are not hapless, misguided souls driven solely by poverty or circumstance; they are people who made a conscious decision to kill. Labeling them correctly — criminals, murderers, perpetrators of atrocities — is essential for moral clarity and for honoring the victims. But moral clarity does not compel the state to kill in return. Condemning their acts and holding them accountable through fair, rigorous trials and long prison sentences denies them the martyrdom they seek while preserving the moral high ground of a democracy that values life even when it is confronted by death.

Hamas, Islamic Jihad, and similar organizations have proven adept at exploiting such symbols. Even now, Israel is holding its breath over the fate of dozens of hostages still trapped in Gaza’s tunnels. As the government’s own hostages coordinator, Maj.-Gen. (res.) Gal Hirsch, pleaded: debating this bill risks the captives’ safety. Families of hostages have warned from experience that when Israeli leaders agitate about the death penalty, captives suffer reprisals. Ignoring those warnings is not strength—it is hubris.

Legal and practical chaos

Beyond the strategic danger, the bill would mire Israel’s justice system in endless legal chaos. Death penalty cases do not end with conviction. They launch years of appeals, petitions and hearings, each one a media circus that broadcasts the defendant’s name, face, and message. Far from erasing terrorists, the courts would elevate them into political figures, transformed from criminals into perceived victims of “state oppression.”

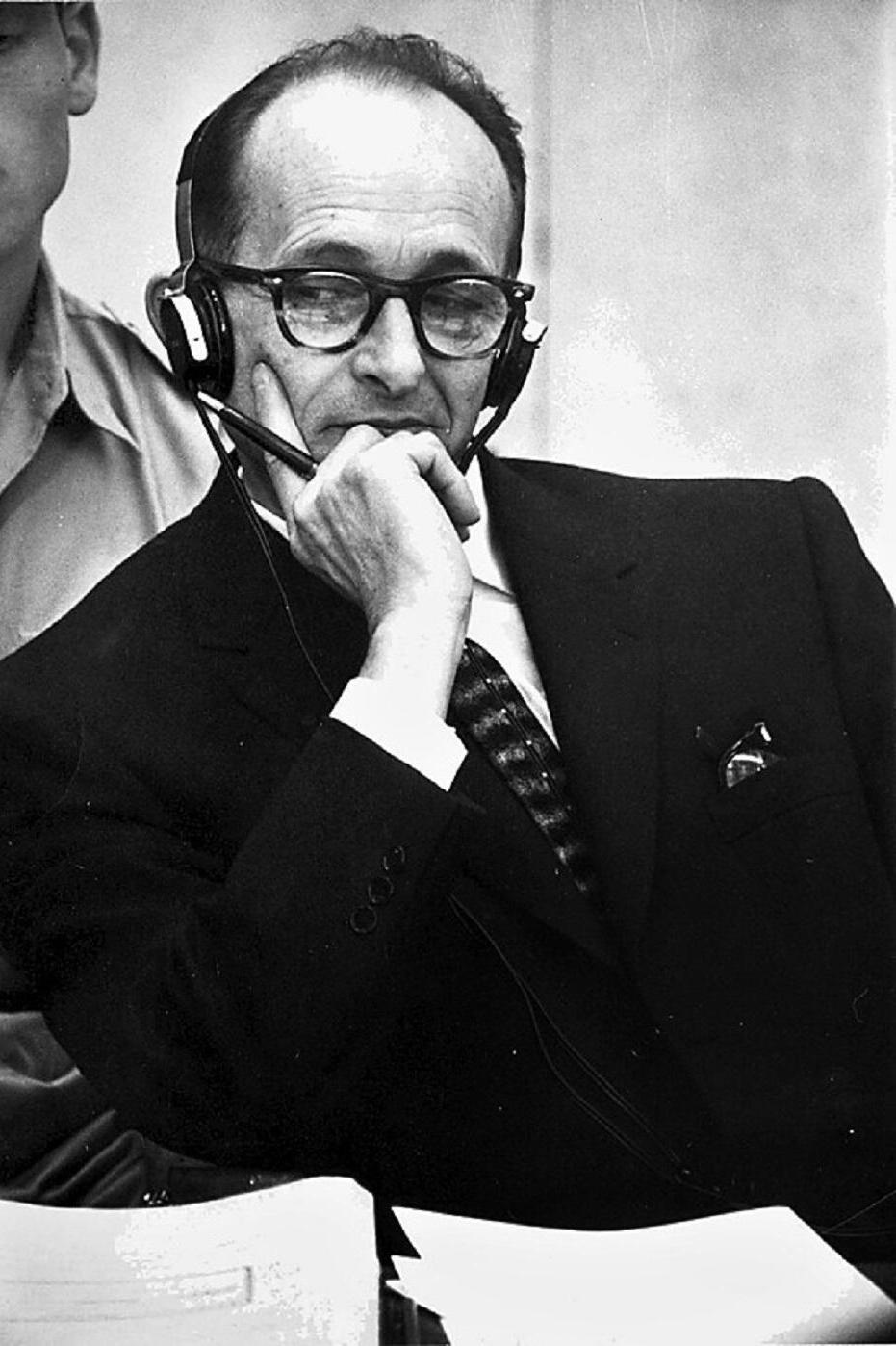

And then the questions multiply: Who will serve as executioner? Where will executions take place? What kind of infrastructure will Israel construct to administer capital punishment—an execution chamber in Ayalon Prison? A gallows in the Negev? These grotesque practicalities expose the unseriousness of the proposal. Israel has functioned for 75 years without institutionalizing capital punishment, except in the singular case of Adolf Eichmann. There is a reason for that.

Lessons From Eichmann and the world

Hannah Arendt’s reflections on Eichmann’s execution are instructive. She warned that turning such trials into moral theater obscures more than it reveals. Eichmann’s death did not bring understanding of the machinery of genocide; it reduced a vast and chilling bureaucracy of evil into a spectacle centered on one man. Executing terrorists today would repeat the mistake, turning ideological actors into martyrs while leaving the system that breeds them intact.

Israel is hardly alone in this conclusion. Most of the democratic world has abolished the death penalty, not because terrorists or murderers deserve mercy, but because state executions brutalize public life, create irreversible miscarriages of justice, and fail to deter crime. Europe, Canada, Latin America, even South Africa after apartheid—all moved away from capital punishment for these very reasons.

The moral case against state killings

There is also a deeper moral argument. A democracy should resist the temptation to act with the same violence as its enemies. The state must embody the values it seeks to defend: restraint, justice, and the sanctity of human life. Capital punishment corrodes those values. It teaches that killing can be justice, that vengeance can masquerade as law.

Jewish tradition itself is deeply cautious about the death penalty. The Talmud states that a Sanhedrin that executed only one person in 70 years was considered “bloodthirsty.” Rabbinic sages so narrowed the rules of evidence—requiring two eyewitnesses, warning the perpetrator in advance, and rejecting circumstantial proof—that capital punishment was, for all practical purposes, impossible. The point was not that murderers should go unpunished, but that the state should never be quick to shed blood in the name of justice.

As Rabbi Akiva and Rabbi Tarfon famously said, had they sat on the Sanhedrin, no one would ever have been executed. This spirit—that life is sacred, that vengeance cannot be the basis of justice—has shaped Jewish moral reasoning for centuries. It is bitterly ironic that those who claim to act in the name of “Jewish values” are the very ones pushing Israel to abandon them.

Punishment must protect society, not indulge revenge. Life imprisonment ensures that the guilty cannot harm again—without granting them the martyrdom they crave, and without burdening the state with blood on its hands.

A pattern of extremism

So why now? Why press a bill that experts condemn, families of hostages oppose, and even Knesset lawyers have deemed improper? The answer lies not in security, but in politics. Ben-Gvir and his fellow Kahanists thrive on spectacle. Their movement is rooted in the teachings of Meir Kahane, whose ideology of Jewish supremacy was banned from Israeli politics for being racist and extremist. Yet today, his disciples hold key ministries and exploit every crisis to mainstream their agenda.

It should not be forgotten that, only a few years ago, Ben-Gvir’s faction could not even muster enough votes to enter the Knesset. His rise was not due to a sudden surge of popular demand, but to political engineering. In the run-up to the 2021 and 2022 elections, Religious Zionist parties were strong-armed by Benjamin Netanyahu to join forces with him, giving Ben-Gvir the electoral boost he could never achieve on his own. Whatever Netanyahu’s personal objections to that alliance may have been, the fact remains that he bears responsibility for legitimizing Ben-Gvir and placing Kahanist extremism at the heart of government policy. This law is not an accident of timing; it is the predictable consequence of that political bargain.

Ben-Gvir’s record is telling:

• He has agitated to break the fragile status quo on the Temple Mount by pushing Jewish prayer at the site, a flashpoint that has triggered violence before.

• He has called for reestablishing Jewish settlements in Gaza, as if returning to one of Israel’s bloodiest mistakes could possibly enhance security.

• He has intervened in police promotions to punish officers linked to corruption probes involving Prime Minister Netanyahu.

• He has dismissed hostage negotiations and declared that “maximum military pressure” is the only path forward, even though military officials and released captives alike say otherwise.

This is not governance. This is radical theater—cheap, dangerous and corrosive to Israel’s democracy and security alike.

What Israel actually needs

Israelis deserve real answers to the terror threat, not stunts. That means bolstering intelligence capabilities, securing borders, pressing for international isolation of Hamas and its patrons, and negotiating responsibly for the release of hostages. It means prosecuting terrorists swiftly and firmly, but within the bounds of law and without turning them into martyrs. It means preserving Israel’s hard-won international legitimacy as a democracy governed by the rule of law, not undermining it with spectacles of state killing.

But it also requires acknowledging a painful truth: violence does not come only from Hamas or Islamic Jihad. Radical settler elements, emboldened by ministers like Ben-Gvir, have also carried out acts of terror against Palestinians. Just as Palestinian leaders must reckon with the poisonous effects of glorifying armed struggle, Israel must confront the danger posed by its own extremists. Both societies pay the price when nationalist violence is tolerated, encouraged, or rewarded.

The death penalty bill is not a solution. It is a distraction, one that satisfies a primal urge for revenge but leaves the country weaker, its justice system entangled, its enemies emboldened.

What is needed now is a shared determination—among Israelis and Palestinians alike—to create a more clear-headed and reasonable environment, one that reduces the appeal of extremism on both sides. People like Ben-Gvir and Hamas thrive on rage, spectacle, and the promise of endless conflict. Real leadership would be the opposite: pragmatic, sober and committed to breaking the cycle of nationalist terror, not fueling it.