Yoav Gallant, has Israel’s government, of which you were part, done everything to bring back the hostages?

“I think the government of Israel has not done everything to bring back the hostages.”

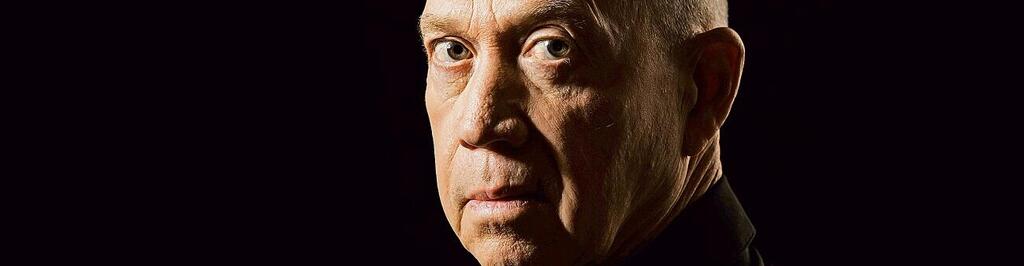

Yoav Gallant has remained silent since his dismissal as defense minister—and, in fact, since the war began. In a rare and comprehensive interview with Nadav Eyal, he shares his account of the war, speaking for the first time. From the chilling 6:30 a.m. phone call from the IDF chief of staff to the grim faces in the Kirya command bunker and the realization that the war’s fate rested on his shoulders.

Gallant reveals his early plan to cripple Hezbollah’s communications—rigging their pagers and walkie-talkies with explosives—alongside a targeted strike to eliminate Hassan Nasrallah at the outset. He details the political maneuvering that delayed a northern offensive by a full year, his warning to Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu during the judicial overhaul, and how Bezalel Smotrich’s leak sabotaged a hostage deal over Passover.

He also speaks about the International Criminal Court (ICC) arrest warrant issued against him and the worsening humanitarian crisis in Gaza.

“We must have a state commission of inquiry,” Gallant declares. If and when that happens, this interview will stand as one of its cornerstone testimonies.

It was a year ago—one of the most harrowing and symbolic encounters of this war. Defense Minister Yoav Gallant toured Nir Oz, unaware that just meters away, Reuma Kedem was standing in the ruins of her family home. It was there that her daughter, Tamar Kedem Siman Tov, son-in-law, Yonatan, and their three children—Shahar, 5.5, Arbel, 5.5, and Omer, 2—were brutally murdered by Hamas.

Kedem had come to the burned-out house to collect toys that once belonged to her slain grandchildren. The massacre in Nir Oz was devastating. Not a single IDF soldier fired a shot that day. Hamas’s Nukhba unit roamed the kibbutz unchallenged, murdering or kidnapping one in every four residents before retreating to Gaza. Security forces arrived hours later—too late.

10 View gallery

'Every word she said was etched in my heart': Yoav Gallant meeting Reuma Kedem in Kibbutz Nir Oz

Kedem saw the defense minister and made no effort to contain her grief and anger. Dressed in black as usual, Gallant listened in silence while the entire encounter was captured by a TV crew. “What is this? How is it possible? My daughter and my three grandchildren…One phone call the night before and Tamar would have been out of there. I have no heart left. My heart is burnt,” Reuma Kedem told him. “This is how you abandoned us… there is a God in heaven! How long will we stay silent? What? A lousy government—what are you doing?!"

Gallant was caught off-guard. He simply looked at the grieving mother and grandmother, and remained silent—displaying a behavior foreign to the government of which he was a member, and essentially to that of the current political culture.

“Look,” he says. “My meeting with Reuma Kedem ranks among the hardest, most moving and saddening in my whole life. I stood in front of her for minutes. It wasn’t planned. I heard her, listening intently. Every word she said was etched in my heart. The most forceful thing she said was why didn’t you tell us? Why wasn’t the IDF here? Why didn’t the IDF show up?”

This is the first interview the former defense minister has given since October 7—and, in essence, since the start of the judicial overhaul two years ago, a time that now feels like a lifetime ago.

Our conversation offers a detailed account of 13 turbulent months in Israel and the Middle East, as seen through the eyes of its defense minister. In January 2023, Yoav Gallant was sworn in, finally reaching the role he had spent his entire career working toward. Within months, he was at the center of an unprecedented political crisis with profound security implications. Nine months later, he was leading a war unlike any in Israel’s history.

As defense minister, Gallant wielded immense influence, drawing on his military experience to unify the defense establishment. With few exceptions, he shaped Israel’s strategy—from the initial response to Hamas’ October 7 massacres to containing the attack and confronting Iran’s so-called “axis of resistance.” His tenure came to an abrupt end on the morning of Donald Trump’s re-election, with a terse letter of dismissal from Netanyahu.

I reminded Gallant of his dramatic meeting at Nir Oz and how we talked about responsibility – his own responsibility, for Israel's worst security failure ever.

His answer: Israel needs a state commission of inquiry. “Everything Reuma Kedem said is correct. Sadly, we can’t turn back the clock. She’s right, from her perspective, for sure. The pain here is immense. That wasn’t my first visit to Nir Oz, nor was it my last. I made sure to get myself to all of the places - Be’eri, Kfar Azza and Nir Oz as well as all of the other communities – Sufa, Kerem Shalom, Holit, Netiv Ha’Asara, and obviously the Nova party massacre site. I met residents and went to see all such sites. I was dealing with stuff from the very first day.”

You were fired by Netanyahu, and then you resigned from Knesset. But it doesn’t seem like you decided your political career had to come to an end as a result of assuming responsibility for October 7.

“I’m not absolving myself of any responsibility. As far as I’m concerned, looking ahead, I think we have to examine what happened, how it happened and why. What happened in the preceding decade. What brought us to this. And all this will happen when there’s a state commission of inquiry.”

When you hear that Gallant visited every massacre site and everywhere Israeli blood was spilled, repeatedly, what you’re not hearing is the subtext of his message about Netanyahu. Gallant is making it clear that he represents everything Netanyahu does not. While Netanyahu has traveled to Washington twice since the war broke out, he has still not found the time to visit the destroyed kibbutz of Nir Oz.

The fired defense minister is calling for a state commission of inquiry—something Netanyahu is actively resisting, with the full support of the Likud party in parliament. Gallant believes Israel needs a universal draft for all its citizens, while Netanyahu has been working on legislation that would essentially allow the Haredi exemption from mandatory army service to continue.

And yet, throughout our conversation, Yoav Gallant firmly refrains from providing an opinion regarding Netanyahu in the war, gauging his abilities or judging his performance. He stresses his desire to speak, “in facts, rather than interpretations or assessments.” And we certainly talked about facts. The first in this story, concerns that bitter morning that changed the Middle East.

Part One

Where were you at around 6:30 in the morning, October 7, 2023?

“I was at home, getting ready for a bike ride. At 6:30 a.m., I got a phone call from my daughter (an Air Force officer), telling me there were sirens in Tel Aviv. I immediately hung up, and a minute later, I spoke with the chief of staff. He said, ‘It’s from Gaza. It’s not just rockets. There’s also a ground incursion. I’ll do a situation assessment and then update you.’ I put on my black clothes (Gallant's black attire became his signature during the war) and drove to the Kirya (IDF headquarters in Tel Aviv). I didn’t return home at all for the next three months. For me, this was the beginning of the war.”

I can imagine you all were in complete shock. It exceeded any possible scenario.

“It was a complete surprise, for me obviously, more than others. They (the IDF generals) didn’t even wake me up in the night for any stage of their consultation. It found me as it was at 6:30 in the morning. On my way to the Kirya, I tried talking to everyone I could: municipal leaders, people I know. It was very hard to directly get reports from the army or the military secretariat. They were all busy addressing the Hamas attack. When I got to the Kirya, I went into the Pit (the IDF command bunker). I think the most striking thing was that people didn’t know what was going on. The picture wasn’t clear and neither was the scope. It was hard to build a situation report of such a wide-scale attack in such a short space of time.”

10 View gallery

'It was a complete surprise': Palestinian bulldozer breaking through the Gaza border barrier, October 7, 2023

How long did it take to build a situation report?

“I went into a room where the chief of staff was conducting a situation assessment with the head of the Operations Division. I gathered everyone together and held a situation assessment at eight o'clock. I quickly told them, ‘One, we’re at war. Two, mobilize everyone we have: regulars, reserves, the entire army. Three, send troops north, including on chains (i.e., tanks on the roads).’ My assessment was that Hamas wouldn’t start a war like this without Hezbollah backing them.

“I then addressed the public, understanding the panic and confusion. I was the first government representative to speak. I said, ‘Hamas has waged war on us. They will pay a very heavy price. We will win.’ From that moment until the end of my role 13 months later, that was my focus—winning the war and achieving its goals, including, of course, bringing back the hostages.”

When did you realize it was actually an invasion? In those early hours, it seemed like we were learning about things from Hamas’s media, from their videos.

"Look, I wasn’t sitting there watching screens. I was conducting situation assessments and discussions, and gradually, a clearer picture emerged. At first, we were dealing with reports of dozens killed, then ‘a few communities’ were affected, and slowly, the scope became clearer. Within an hour, I understood we were facing a large-scale event. I just didn’t know the full extent of it. The next day, I was in Ofakim, Be'eri and other places. I saw it firsthand—the breaches in the fence. I think the fog of war and the sheer surprise of it all prevented the IDF and Shin Bet from having a clear and coherent situation report."

When did you and the prime minister first talk?

“As far as I remember, during the situation assessment we did in the morning hours.”

What were the prime minister’s instructions?

“I don’t remember anything specific. I think we discussed calling up the reserves. In those early days, I set the goals for the war, and the Security Cabinet simply adopted them. I sat down, wrote them out, and presented what was needed, like calling up the reserves. That was under my authority for a while. But shortly after, it was transferred to the decisions of the Security Cabinet and the government.”

Would you describe the prime minister as dominant in the first month of the war?

“Let's put it this way. When I went into the Pit, I very quickly understood this was a large-scale event, that the responsibility on me had no substitute, and that in many ways, the fate of the war rested on my conduct, decision-making, setting a personal example, expressing composure, support, representing and leading it all. It was clear to me from the start, that all roads led to me.”

Later in the interview, when Gallant described Netanyahu’s “pessimistic” approach at the start of the war, I pressed for a clearer assessment of the prime minister’s performance and returned to the point:

Some say Netanyahu wasn’t functioning, that he was in a state of shock for the first month. Is this true?

“I’m not getting into this kind of analysis.”

You don’t want to address the issue of whether Netanyahu was in state of shock?

“I don’t. I’ve no understanding of the angle you’re describing, and so I’m describing the factual matters – what happened and what was said.”

Okay. Shortly after the Hamas attack began, the IDF activated the “Parash Pleshet” order, an emergency response to hostile incursions, which granted division commanders the authority to use military force within Israel’s borders. Then, the IDF implemented a directive known in the media as “Hannibal,” aimed at preventing kidnappings, even if it meant putting Israeli hostages’ lives at risk. Were you involved in these decisions?

"You have to understand the scale of what was happening. There were infiltrations at dozens of points. The division commander was engaged in fighting Hamas at the division base, holding his ground inside the headquarters while they fired at his position. A southern brigade commander was killed. People were running into battle. What you're describing are local operations. My orders were clear: close the border, eliminate anyone in our territory and stay in contact with local municipal officials. I assigned each leader a representative to coordinate directly with the army. The reason for this was that I recognized the pace of execution was slow. The IDF’s real problem at that time was the failure to act the night before."

Gallant repeatedly refers to that night, often using the word “frustration” in different ways. This was the night that SIM cards, secretly planted by the Israeli Shin Bet to provide early warning of a possible Hamas attack, were activated by Hamas fighters. Other signals were intercepted by Israeli intelligence and Shin Bet, but they were mostly interpreted as part of a possible Hamas drill and not as a sign for an imminent attack.

The Military Intelligence chief, the head of the IDF Southern Command, the chief of staff and the head of the Operations Directorate were all notified. They woke up, held discussions and issued instructions. Gallant says the IDF was effectively operating from that night onward based on a situation assessment that assumed, at worst, a limited attack.

"It’s not that bad people didn’t update me. They’re all good people." Still, for him, the fact that they didn’t wake him up that night remains “the greatest frustration of my life.”

Why?

“Because they deprived me of the last point in which I could intervene. Ultimately, the defense minister can intervene days or hours before such an attack, giving instructions and supply trajectories. He’s not standing there at the fence with a gun, and he’s not commanding a battalion, zone or command region. This really is the most frustrating point. Why? Because I’m used to being woken up in the middle of the night. I’ve been woken up a lot. I’ve always taken it seriously. I’ve always given the most stringent of instructions. From all my life experience, there’s one thing I know for certain I’d have done. I’d have told them: ‘I hear the situation assessment and what you’re doing. Let’s assume your situation assessment is lenient. What General Staff operations, what troop deployments are you ordering to secure the situation for the eventuality that you’re wrong, and something worse is going on?’ Just by asking that question, I believe something would have happened. More aircraft would have been sent into the air. All commanders would have been put on high alert. Maybe additional battalions would have been mobilized. In the end, by the morning hours, there were only four battalions in the sector—everything else takes time to mobilize and organize.”

There’s a debate over, ‘Why didn’t they wake up the prime minister.’ The question isn’t actually why they didn’t wake up the prime minister, but rather why they didn’t wake up the defense minister. Have you asked the chief of staff, ‘Why didn’t you wake me up?’

"The answer is simple—they didn’t think it was serious enough. That’s why they didn’t take all the necessary actions. They didn’t scramble the entire Air Force. They didn’t mobilize all available forces, and certainly not all the commanders. Why go far? In some battalions, there wasn’t even a state of alert at dawn. What does that mean? It means that this was an event where the battalion commanders weren’t even told there was a potential security threat. And by extension, it also means that the defense minister wasn’t woken up. But I don’t know everything. This, of course, follows a long series of intelligence reports that came in over the years—reports that weren’t acted upon as they should have been.”

From everything you know in hindsight about that night, including as someone who was the defense minister at those critical moments—what, in your view, was the most obvious military mistake during those hours leading up to the attack? The most glaring one?

"It’s a bit presumptuous to give a definitive answer about such a massive event. I think it comes down to what I told you I would have done. In a situation where there was a failure to fully understand the intelligence in advance, you have to mitigate the risk through actions that take a worst-case scenario into account. The scenario they considered dangerous, and the actions they took in response, were not aligned with the actual threat. Of course, this is also tied to how threats accumulated and were handled over the years.”

Gallant gives me an example—Operation Shield and Arrow, the campaign against Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ) in Gaza a few months before the Hamas attack, during which the entire security leadership held hundreds of situation assessments over two weeks, focusing in "maximum detail" on PIJ and Hamas, fearing that Hamas might intervene.

"And yet, not a single person stood up and said that Hamas had an offensive plan—one that included the possibility of seizing parts of the Negev or entire communities. What we later came to know as the Wall of Jericho plan."

When did you first hear the words, ‘The Wall of Jericho’?

"About a month after the campaign began. In my view, the real story is that both the name and the plan were known to senior officials in the military high command. They were familiar with it (the Wall of Jericho scenario). And yet—again, these are not bad people—despite their awareness, it didn’t sink in, and the result was never presented to me. The possibility or course of action in which Hamas would carry out something far more ambitious than we had assessed was not fully considered."

I saw the public statements given by the prime minister and yourself following Operation Shield and Arrow. Israel’s military and political echelons took pride in the fact that Hamas did not intervene and argued it is deterred. In retrospect, it turns out that Hamas was deliberately reserving its forces for a huge attack on Israel.

“As defense minister, I was relying on three basic channels of information. Firstly, what comes up about the enemy in intelligence, secondly; what comes up in discussions and situation assessments that make their way to me, which ultimately goes through all the echelons, and thirdly; my going to the field and meeting brigade and battalion commanders, and certainly division commanders and the generals. This delves deeper and is more specific to each sector. In all these places, and by all these methods and stages, including during Operation Shield and Arrow, but in other scenarios too, there was no information anywhere – neither in the information channels nor the discussions or observations channels when something happens (as to Hamas in Gaza). I’ll tell you more than that: When I was visiting the Gaza Division, on more than one occasion, I told them, ‘Look, the defense minister, chief of staff and the prime minister have strategic intelligence. Don’t rely on it. Do what you’re good at – observation, patrols, stakeouts, tactical monitoring of communications. Everything you can give that increases our capabilities. Show your advantage in the field.’”

When asked about having no intelligence coverage of Hamas walkie-talkies, the spotter soldiers’ warnings and the general Military Intelligence's failure, specifically in the elite Unit 8200 where senior personnel were not called in from their homes that night, Gallant says he’s not getting into the operational side: “At the end of the day, I’m defense minister with a dozen echelons beneath me who have to the work. But, ignoring tactical intelligence is, without a doubt, has been at the heart of the whole issue. If you ask me what I saw – and by the way, I made these comments in the Northern Command too – there’s an ever-increasing addiction to strategic intelligence which is higher quality, but it isn't the bread and butter and the foundation of tactical power.”

A week and a day before Hamas attacked, on the first day of Sukkot, the defense minister goes down to the Gaza border, on his own initiative.

Instinct, perhaps. “In afternoon hours, I told my people that I want to go to the Gaza Division, to see what’s going on. For no particular reason. We don’t need the chief of staff or division command. I was told the northern brigade commander is on duty and I go to meet him. Me and him. We looked over Gaza and I asked him questions: What was going on here and there, and whether they’ll get past. He explained the technique (of the barrier) and how they’ll trap them between the fences, the Hover's Axis (the road on the perimeter fence with Gaza). I then went to the nearby Iron Dome battery. I’m telling you this because I’m trying to show that I was trying to best understand what was going on in the sector. But in the end, you have to rely on what the intelligence and commanders tell you.”

And you had no indication.

“I am frustrated. For the entire year, or for nine months, they were in no way giving any kind of information about anything materializing (in Gaza’s Hamas). I met with the present general officer commander (GOC), the previous GOC, the chief of staff, the previous chief of staff in the first month we were together. Not a word. Any activity on the fence – like friction and disturbances in the month leading up to October 7 – were explained away as efforts to draw concessions regarding the number of daily workers [permitted into Israel], aid to Gaza and similar aspects. That’s the explanations I received.

Moreover, you knew secret negotiations were underway in Cairo at this stage, regarding the possibility of bringing back Israelis [Avera] Mengistu and [Hisham] al-Sayed, and the bodies of [Hadar] Goldin and [Oron] Shaul. In other words, Hamas was deceiving the Israelis.

"There is no doubt that this was a deception that successfully misled Israeli intelligence. I left the sector 12 years earlier—that was the last time I was in the chain of command. Since then, there have been three IDF chiefs of staff, six defense ministers, and one prime minister for most of the time. When I left, there was no underground city in Gaza, and there were no attack tunnels penetrating into Israel. We were on the verge of breaking Hamas' back in Operation Cast Lead, but I didn’t receive approval from the chief of staff and defense minister at the time. So I had a certain perspective. Throughout all these years, there were people in the most central positions, specializing in this sector—and in the end, you rely on these systems."

"When I left, there was no underground city in Gaza, and there were no attack tunnels penetrating into Israel. We were on the verge of breaking Hamas' back in Operation Cast Lead, but I didn’t receive approval from the chief of staff and defense minister at the time."

Gallant says that when he took office, he intervened in the IDF's preparations in the north in response to Hezbollah’s public plans to invade the Galilee. “I told them, you are not prepared for a large-scale offensive by Hezbollah.” He discussed the matter with the chief of staff three times and demanded preparations as if Hezbollah’s Radwan Force—a specialized commando brigade trained for cross-border raids—was "a division on the border."

“As a result, they began working on fortifications, reinforcing airpower, and initiating artillery-related operations. I give this as an example of a situation where I had a ‘sensor.’ That’s why it frustrates me so much that I had nothing (ahead of Hamas’s attack from Gaza), and in those final 24 hours, in the last few hours, I wasn’t even aware (of the overnight consultations). That frustrates me enormously. To influence things as defense minister, I need some kind of foothold. If I had even the smallest foothold, I would have used it.”

Let’s get back to that morning. There’s another problem emerging – that of command and control, beyond the fog of war. Hamas had taken down the communications lines, taken over junctions. Each tank was working alone.

"In the first hours, the IDF was in a situation where it was under attack by Hamas, but in reality, it was facing a commando division of 4,000–5,000 fighters, equipped with boats, drones, motorized gliders, 4x4 vehicles mounted with heavy machine guns, Hamas command posts, communication devices, and even Hamas medical teams. There was a severe force ratio problem—this was the core issue. They were fighting against four battalions that were on low Sabbath readiness. Once key commanders in the sector were hit—like the brigade commander and others who were wounded—the battlefield became decentralized, and there was no overall control. This didn’t happen at the General Staff level. I doubt—this needs to be investigated—what was happening at the regional command and division levels. But if you ask me, that was the moment when the consequences of previous errors became irreversible."

I ask Gallant whether the atmosphere was like in the Pit in 1973, two days after the Yom Kippur War broke out, when Defense Minister Moshe Dayan was talking about the "fall of the Third Temple -" the possibility of Israel being wiped out. He instantly rejects this.

“I told people we were at war. We’ll win. The confusion and lack of data was immense, but I don’t think the chief of staff was in any kind of situation similar to what you’re describing. He wasn’t losing his composure. He was controlling things in the emerging situation. Throughout the first days, however, and even on that day, I saw people who had to sit in the first row, as I sat at the head of the table, who suddenly moved back to the second row – and weren’t there. I suddenly saw that the personal burden on their shoulders resulting from the failure was very heavy indeed. Without saying it in words, I held them accountable. I asked them questions and brought them back into the circle of operation. Because I understood that with this composition, we were going all the way to victory.”

You mention former Military Intelligence chief General Aharon Haliva.

“I didn’t name names.”

There are two arguments here. The first is how such a surprise could happen. The second – the surprise has already occurred. How is it possible that the IDF didn’t arrive in time? The all-powerful IDF couldn’t arrive and recapture, let’s say, any kibbutz or village by 1:00 p.m.? Even if there was an invasion of thousands of terrorists?

“I think it’s a matter of IDF response. At the end of the day, the IDF needs to bring troops from somewhere, organize the troops in Judea and Samaria or at a training ground, get them on trucks or helicopters and transfer them. That’s the time it probably took. The special forces landed earlier, and showed up. Sadly, they paid a heavy toll with many killed in all of these units, who really did an incredible work.”

Even after speaking with former chiefs of staff and security experts, it remains unclear – how could it be that Israelis were screaming for help from bomb shelters in kibbutzim for hours, and it was being broadcasted, while for hours they were telling us the terrorists were on the other side of the door? Did you, as a decision maker during this time, and your colleagues, understand the situation of thousands of Israelis under siege?

"I’ll put it simply: A) The situation was unclear. B) The defense minister doesn’t stand with a rifle or even a radio. In the end, the IDF is responsible for conscripting every eligible man and woman each year, providing them with basic training and equipment, with unlimited powers and billions of shekels to ensure security. That’s their job. But there’s no doubt that the price for the lack of warning was the delay in halting the threat. And that delay was 12 hard hours. The first six hours were especially difficult. Since the situation wasn’t clear, the roads were blocked, and no one was reporting, etc. – in this chaos, it was the frontline officers who solved the issues. It was the bravery of the soldiers that helped the IDF hold the line. The clearest example is the number of senior commanders, lieutenant colonels and others, who were killed in the first days. When you understand that, you realize where the army was. Brigadier generals fought with knives, and generals killed terrorists with pistols."

"Everything has to be investigated." Oct. 7 attack

(Reuters)

And reservist generals like Yair Golan and Israel Ziv, went down south with guns and rescued people, including from the Nova party. The displays of bravery are beyond doubt. Still, the expectation is that the government, the defense establishment and the IDF should be able to provide adequate containment within the territory of the State of Israel within a few hours.

“The catastrophe of it all was the encounter at zero range, a head-on collision. This means the braking distance took hours. The military apparatus wasn’t ready. The communities and soldiers paid the price at the line of contact, and the price was horrific. I saw it with my own eyes. At the end of the day, there’s one thing you can’t ignore – this is the army’s task. This is what it’s there for. This is one of several issues, I believe a commission of inquiry must investigate. It can’t be an internal investigation conducted only by the IDF. Everything has to be investigated, to see what the general directions were, what the instructions were, what troops were operated.”

If Hezbollah had launched a surprise attack that morning in the north, could the existence of the State of Israel have been at risk?

“I don’t think it was in danger.”

In October 2023, it was 50 years since the Yom Kippur War. political and military leaders were giving speeches about lessons learned. One of the Agranat State Commission’s conclusions was to prepare in accordance with capabilities, rather than threats and intentions of the enemy. Was the problem that intelligence was telling you Hamas didn’t have the capability?

“None of this was in anyone’s spectrum of thought. The best example for this: Before assuming my rule, compulsory military service was cut down from 36 to 32 months. What does this tell us about what Israel thinks about threats?

“When I assumed office, the allocation of funds to the IDF budget in real terms was decreasing compared to GNP. What does this tell you about where we were? I could carry on. At the end of the day, when you look at the tunnels in Rafah, we’re talking about things over a decade. These aren’t things hidden from view.

“Another example: in my first days as defense minister, I do what we call an inventory, a power assessment. It turns out, in 2022 the Americans took 200,000 artillery shells the IDF was counting on for the war in Ukraine. These are the American military warehouses. Another 50,000 were due to be taken in the summer. I asked the previous defense ministry director-general what they were doing about it. They told me – 'nothing'. Along with the new director-general (Eyal Zamir), I told Elbit (an Israeli defense contractor) to start producing artillery shells, and they did. When the war met us in October, the machines were already working. Without this, we’d have been six months behind. I got something where the state of mind was very much removed from a widescale attack on all fronts. It also had no intelligence backing.”

What about your personal responsibility as defense minister? For example, the transfer of funds from Qatar to Hamas, or the idea of a settlement with Hamas. That's in your time in office, too. Even if you weren’t aware of "The Wall of Jericho"—just as critics think Netanyahu should take responsibility and step down, so should you.

“A state commission of inquiry, that will objectively discuss all the details, not just in the army sector, but rather a decade back and the public will decide the rest. I’m prepared to be put to the test, any investigation, any procedure. That’s it. I can’t address everything that’s said. At the end of the day, I can only address what I know and what I’m familiar with.”

You were the defense minister. Whether you knew or not, you’re responsible.

"On responsibility, I spoke about it in the first days, in the staging areas. That’s why I said, 'Let’s establish a state commission of inquiry.' There is direct responsibility for those in charge, those with the ability to give orders. There are those who must provide the intelligence. There is also contributory responsibility for other matters: billions of dollars flowing from Qatar to Hamas, building the military infrastructure, the tunnels, all of it. There is a process that has escalated, with actions aimed at division within Israeli society, creating a growing weakness in our security structure. The dangerous part is that the enemy identified this as a point of vulnerability, and perhaps an opportunity. So much so that the enemy, in general – not just Hamas – asks itself: 'Do I need to help Israel collapse, or will it collapse on its own?' That’s why I’m so concerned about this issue and made my statement. I thought it was the last thing that could still be done."

Gallant is referring to his speech on March 25, 2023, in which he warned that the government's judicial overhaul must be halted and a compromise reached, citing a "clear, immediate, and tangible danger to state security." This public statement led to his dismissal by Netanyahu, which triggered the now-famous "Gallant Night."

On that night, hundreds of thousands of people took to the streets in widespread civil disobedience, preventing Gallant’s dismissal and halting the judicial overhaul. However, it was clear to political observers that, in the long term, Gallant’s public opposition to the prime minister would eventually lead to his removal.

Gallant recalls that before delivering the speech, he told his family he likely would be fired. "I spoke with my family about it. I told them, ‘I’m going to give a speech. I estimate a 20 percent chance that a few people will join me and share my opinion—despite not coordinating with anyone. This could lead to a halt in the overhaul. But I estimate an 80 percent chance that I’ll be fired and home by next week.’ I told them I was willing to take the risk. Look, being defense minister is the job of my life..."

And you had only been in the position for two months.

“Two and a half, I’d done all I could to reach this position. I believed I’d do the job for a long period of time. Yet as I’ve done my whole life, I put the good of the country and the IDF before my own. That’s to say - to anyone with any doubts about where my principles and sense of responsibility lie - when I see warning signs, I act.”

The speech came following failed talks with Netanyahu. Gallant says that three days earlier, Netanyahu had promised him he would “take steps,” but then, "went public" and "said different things." Gallant says he received disturbing prior reports from the heads of the Military Intelligence and its Research Division, Shin Bet and Mossad, all confirming the severity of the situation.

“Look, I met with Netanyahu regarding the issue ten times or more. Apart from that, the chief of staff, the Mossad and Shin Bet chiefs, both together and separately (issued warnings, n.e). The Military Intelligence chief too. What I said in the speech wasn’t against judicial reform, but rather that we had a greater security urgency – that our enemies had identified an opportune moment.”

You’re saying you met with the prime minister ten times regarding “the issue.” Regarding what exactly?

"I spoke to him about the urgent need to halt the reform process, as it was putting us in a dangerous situation that we couldn’t afford. I told him that it didn’t matter who was right or who started it—the outcome is what counts. We cannot give our enemies an opportunity to exploit the situation. I saw it as a major threat. I have to clarify that Hamas wasn’t my primary concern. What worried me more, based on the intelligence—though nothing concrete had been identified—was the growing power of Hezbollah and Iran."

You’re saying you identified an immediate threat to national security, amid the ongoing legislation. What was in the intelligence?

“Clear danger. Clear and present. That’s what I said in the speech. Our enemies have identified a weak spot. They thought that Israel was on the path to collapse. Some of it was said publicly, some behind closed doors. By the way, I wasn’t against judicial reform. I think changes must be made addressing the balance of power between the judicial system and the government and Knesset. But you can’t come along with six immediate reforms four days after forming the government without the defense minister being updated – and I don’t know who was – and expect this to be a national priority without any major discussion.”

If that’s the case, and there was a sense of clear and present danger, did you order any change in the IDF deployment?

"My directives focused mainly on Iran and Hezbollah since we had intelligence that they were stronger. As for the north, I’ve already detailed what I did. The second thing is that, in my first three months in office, a team of experts worked to provide the defense establishment with additional perspectives on our plans regarding Iran. This team was led by former IDF chief of staff Shaul Mofaz, and included three other generals and two further senior officials. Following their conclusions, I conducted a war game exercise with the IDF in July 2023. Based on that, I issued directives the principles of which stated that if, for any reason, we get into a confrontation with Iran—deterrence alone is not enough. The whole conflict must end with them weaker and us stronger. And that was the basis of the successful October 26, 2024 operation against Iran."

Netanyahu's supporters argue that if you thought the situation was so severe, and there were warnings—and the warnings weren’t just a political ploy to thwart the judicial reform—why weren’t deployments made on the borders, including in the north?

"I’ve told you why: when I came into the job, mandatory military service was down to 32 months rather than 36. When I came into this role, I set up a ministerial committee about the reserves. There were 60,000 active reservists serving more than 21 days a year - for which the government refused to pay. I sat with ten ministers and some asked me, ‘Why do we even need a reserve army?’ This is in the summer of 2023. The IDF operates with the resources it has. Had there been a specific threat, we’d have prepared for it. In defense, which is the basic situation, you allocate all the resources—certainly the troops, etc., and distribute them across each day. For the enemy, every day and every hour is an opportunity to attack. If you don’t know when [the attack will be], you spread the resources across the board the best you can. Now, you can’t stop training for a whole year. Under the given circumstances, the IDF was on the highest level of readiness it could maintain for months at a time. That’s the story."

Gallant is visibly angry. "When all the security bodies are saying there's a tangible danger, an increased threat level, it’s unimaginable not to take it seriously. To present the problem as if it’s just the IDF’s or the security system’s issue – while it’s a national problem of the highest magnitude – the most glaring example is that I had to speak publicly for this to stop in the end. We were warning to do two things: One, allocate resources. Two, take action to stop the root cause of the threat. Neither of these things were done. Resources were not allocated. The issue (of Israel’s enemies recognizing an opportunity) was not given the proper national attention. At the same time, while I’m trying to convince (ministers) – I'm trying to demonstrate to you how these things were not being taken seriously – we see that what could be a powder keg, we don’t know in which front, is Ben-Gvir's visits to the Temple Mount. No one is stopping this."

Netanyahu might respond by saying the problem was that the security apparatus failed to properly address the protest movement that infiltrated the military—reserves announcing they would not volunteer for service, broadly referred to as a refusal to serve. According to the prime minister's associates, this failure played a key role in enabling the Hamas attack.

"This doesn’t warrant a response. This isn’t someone else’s country. We have an elected government. It has a prime minister. As far as I am concerned, refusing to serve is extremely serious. I’ve fought against it my whole life and I continued to fight against it. All these slogans are lies and nonsense. We addressed refusal to serve very decisively at many junctures. I didn’t allow former chiefs of staff to come into the IDF and speak as they’d said something that could have been interpreted as supporting it. And the test of what really happened is the real test. In the end, a war broke out. The reserve army turnout rate was 150–200 percent beyond anything the IDF needed. The way we handled it, when put to the test, October 7 saw everyone, without exception - double the numbers needed—show up. And yet - at the end of the day, in a democratic country, people can say whatever they like and do whatever they want, but they can’t use their positions [in the army] and ranks to add credence to what they say, and certainly not coerce an elected political leadership.

Part Two

The most important daily meeting in Israel during the first year of the war took place at the Defense Ministry. Starting in the third week of the war, Gallant convened top security officials every morning at 10:30 a.m. ("exactly," he notes, "and not on Zoom"): the IDF chief of staff, the heads of the Shin Bet and Mossad, the Defense Ministry director-general, the head of the Hostages Directorate, the coordinator of government activities in the territories (COGAT), the IDF spokesperson, the Home Front Command chief and others. "This was highly effective," Gallant says. "It was the beating heart of the entire process. And I insisted that the top officials themselves be there, not their representatives."

A similar, though smaller, meeting laid the groundwork for the current hostage deal. In hindsight, Netanyahu privately described the proposal as an "ambush" orchestrated by the security establishment.

The former defense minister assessed that it was unlikely Hamas leader Yahya Sinwar would have launched the war without some level of coordination with Hezbollah chief Hassan Nasrallah. "Indeed, months later, we found in Hamas computers in Gaza Sinwar’s speeches (to senior Hamas officials), as well as orders, discussions and coordination efforts. As early as the summer, they had sent people to coordinate with Hezbollah."

This story is closely tied to a relatively unknown figure in Israel: Saeed Izadi, head of the Palestine Branch in the Quds Force of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC).

Last week, the Intelligence and Terrorism Information Center published a detailed report on Izadi, based on captured documents from Gaza. These documents underscore the extent of Iran’s influence over Hamas and Izadi’s role in planning the “great campaign” that became the October 7 attack.

In July 2022, Hamas political leader Ismail Haniyeh reported to Sinwar about a meeting that Izadi had arranged with Nasrallah. Haniyeh confirmed that Nasrallah viewed the destruction of Israel as a realistic and imminent scenario and that the Iranian representative sought to examine Hamas’ plans in depth.

A year later, senior Hamas official Khalil al-Hayya, a close associate of Sinwar, traveled to Beirut carrying a message about Hamas’ intention to launch an attack soon. For reasons that remain unclear, Nasrallah refused to meet him. Instead, al-Hayya met with Izadi and informed him that Hamas would strike Israel. Yet it does not seem that Nasrallah knew or acted upon this.

It can now be reported that during negotiations between Hamad and Israel for the return of Israeli captives and bodies from Gaza, just before October 7, one of the ideas proposed by mediators—originating from Hamas—was to grant Sinwar permission to leave Gaza for abroad, something he desired. The matter reached Gallant, who immediately rejected it. Had Sinwar traveled to Beirut, there is no doubt Nasrallah would have met him; the message that his associate al-Hayya had delivered about launching a war against Israel during the holidays would have reached Hezbollah's leader. And who knows what might have happened on October 7.

For the first time, Gallant now reveals Sinwar’s strategic directives on October 7 itself, based on captured Israeli intelligence. "Sinwar said there was a 'small plan'—that was Hamas. We would conquer the entire western Negev. There was a 'second plan'—that Hezbollah would join, seize the Galilee, and create a major threat. And if Iran joined, we would eliminate Israel."

Gallant says he quickly realized the need to restore Israeli deterrence. "When about 1,200 of your people are killed on the first day, then to reestablish deterrence, you need to eliminate the organization that attacked you. Because even if you kill 12,000 people, that’s an acceptable ratio for Hezbollah—and tomorrow, they will go to war against you."

10 View gallery

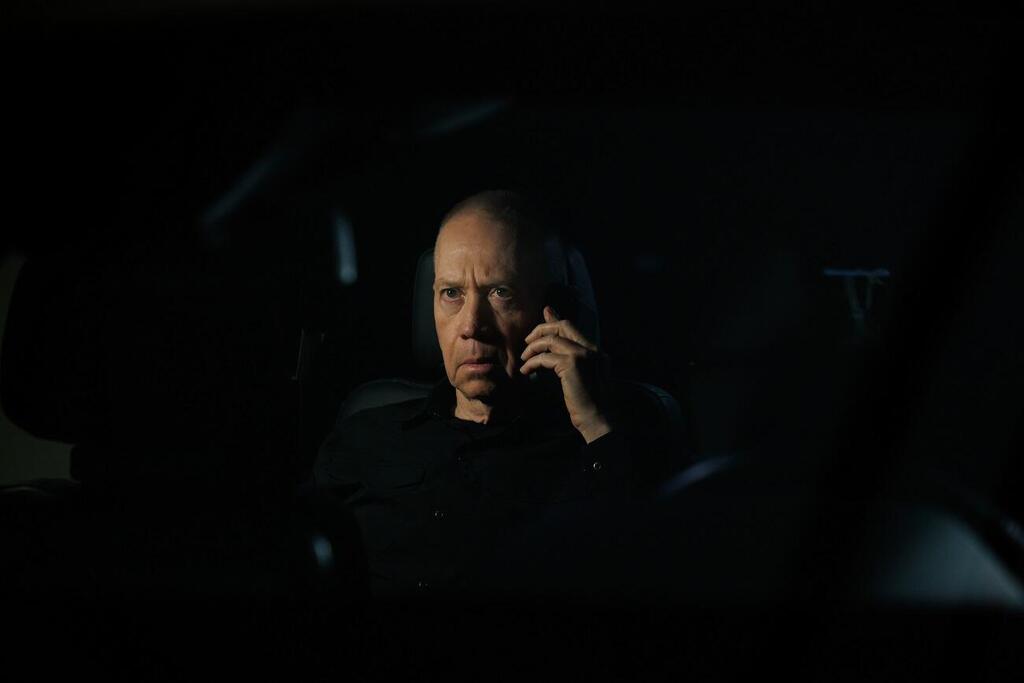

The prime minister said, 'Operate from the air'

(Photo: ABIR SULTAN POOL/Pool via REUTERS)

The objectives, as he defined them and which were later adopted, included dismantling Hamas' military capabilities, securing the return of the hostages, eliminating Hamas' leadership and eradicating its governing authority in Gaza.

"I estimated that Hezbollah would join the war, and on the second day, October 8, they indeed began firing. At that point, we were fighting against an axis led by Iran, extending through Hezbollah to Hamas. I coined the term ‘the seven-front war.’ And from the first day, it was clear to me that in order to achieve our goals, we would need to conduct a ground operation to take over all of Gaza and dismantle its infrastructure. It was evident that there were unknowns—we had never fought in a battlefield filled with tunnels, and our experience in densely built-up areas was limited. But I told everyone who would listen, including within the IDF: through a ground maneuver, you destroy Hamas' strength, create conditions for retrieving the hostages and facilitate a regime change. Some said, 'Negotiate with them. Give them whatever they want, and they'll return the hostages.' I replied—under no circumstances."

There have been claims that an early deal could have brought all the hostages home at the start of the war.

"That was never the case. During those days, Hamas was even demanding Israeli concessions in Jerusalem and Judea and Samaria. At no point in any discussion was a deal like that proposed, and I am unaware of any intelligence supporting it. On the other hand, I saw what Hamas was saying. When we began mobilizing forces, they dismissed it as mere media theatrics. When we started minor maneuvers on the outskirts of Gaza, they said we wouldn't cross open terrain. When we entered the open areas, they said we wouldn’t go further. Slowly, they began to understand what was happening."

At the time, Yedioth Ahronoth reported that Prime Minister Netanyahu opposed a ground incursion into Gaza for weeks, fearing the IDF would suffer thousands of casualties.

"The prime minister said, 'Operate from the air. If we conduct a ground maneuver, we will lose thousands of soldiers.' I told him, ‘Mr. Prime Minister, first, we will not lose thousands of soldiers. Second, what is the army for, if after 1,000 of our civilians are slaughtered, we don’t move in?’ This was part of the same debate we will discuss in relation to October 11. There was a deep skepticism about the IDF’s capabilities and a severe sense of pessimism."

Gallant praises IDF Chief of Staff Herzi Halevi, saying he was "highly effective" in executing the maneuver plan in Gaza, which included a large-scale deception of Hamas in the first two months of fighting: "A combined operation was conducted at the highest level."

There were reports in Israeli and international media that you authorized strikes on the homes of all Hamas members, even if their families and uninvolved civilians would be killed, and that the identification of these targets was assisted by artificial intelligence.

"In terms of operations, you should discuss that with the military. Both the IDF chief of staff and I insisted that targets be strictly legal, in accordance with international law, and approved by the military advocate general. But I must emphasize the context. There are two million civilians in Gaza. At the outset, we had 251 hostages and around 1,200 people killed. These are factors that must be balanced. The country is fighting for its survival—not necessarily in the sense of physical destruction, but in terms of its standing and deterrence in the Middle East. Otherwise, Israel’s long-term viability is not guaranteed. This brings me to October 11."

"From day one, through the first weeks of the war—at least until the conclusion of the first hostage deal—the PM projected a deep sense of pessimism, which I did not share... On this issue [war with Hezbollah], more than once he pointed out the window of his office and said, ‘Do you see all these buildings in Tel Aviv? They will be destroyed because of Hezbollah’s residual capabilities.’"

For the first time, Gallant publicly reveals details of that dramatic Cabinet debate, in which ministers decided—against his recommendation and that of nearly the entire security establishment - to reject a large-scale preemptive strike on Hezbollah. He does not mince words about the decision. Here is a concise account of one of the most ambitious military plans ever presented to Israeli leaders:

"I believe that failing to act against Hezbollah on October 11 was the greatest missed opportunity in Israel’s military history. From the moment Hezbollah opened fire, it was clear we were confronting the Iranian-Hezbollah-Hamas axis. When you fight multiple enemies, you must strike the strongest one first. I didn’t invent this; it’s classic military strategy from [Carl von] Clausewitz—if you start with the weaker enemy, you won’t have the strength left for the stronger one. That’s why I told them: ‘We must begin with Hezbollah.’"

The plan for action against Hezbollah had three components. “First, there was an opportunity to eliminate senior Hezbollah leaders, including Iranian operatives and top commanders, from Nasrallah down. Immediately afterward, the IDF would have launched a large-scale strike on Hezbollah’s rocket and missile infrastructure, similar to what was ultimately carried out in September the following year. In 2024, Israel managed to neutralize about 80% of Hezbollah’s missile capabilities, but on October 11, the military could have achieved over 90% destruction, as many of the rockets were still stored in depots and had not yet been dispersed. The third phase involved a ground maneuver, during which thousands of Hezbollah fighters would have mobilized, wearing vests equipped with communication devices that could be remotely detonated, effectively eliminating between 12,000 and 15,000 operatives in an instant. This would have led to the large-scale destruction of Hezbollah’s leadership, its arsenal and its fighting force.

From that moment, the situation would have been entirely different. Why? Because it would have created an opportunity to shorten the war. The IDF could have shifted divisions from the northern front to the south, allowing simultaneous operations in Khan Younis and Rafah alongside the fighting in Gaza City. There would have been no need to evacuate northern Israeli communities, and Hamas would have lost its entire strategic support—both physically and morally. All of this could have been achieved under near-ideal conditions: Hezbollah had already opened fire across the northern border and was issuing direct threats; the IDF had a fully mobilized reserve force, with three divisions deployed for defense in the north; all Iron Dome batteries were operational and fully stocked; international support was at an unprecedented level; and national unity was stronger than ever following the horrific October 7 massacre. On top of that, Israel had complete strategic surprise.

"I believe this was the most critical turning point of the war after October 7," Gallant says. "And we took the wrong path. We corrected it a year later."

Gallant recounts that the decision-making process began taking shape on October 10. He and those present understood that, due to the narrow operational window (of the Hezbollah leaders meeting), everything would come down to a final decision the next day. He did not sleep that night, instead holding a series of consultations with experts and military officials who were urgently summoned to the Kirya. At 8:00 a.m., the IDF General Staff presented him with operational plans for the strike. By 10:00 a.m., he met with the chief of staff. "It turned out that he had reached the same conclusion independently," Gallant says, meaning the operation was feasible with a high likelihood of success. At 11:00 a.m., the defense minister went to meet Prime Minister Netanyahu.

What Gallant describes from this point is a rare and unprecedented glimpse into Netanyahu’s decision-making circle—not regarding an event from many years ago, but less than 2 years ago.

"I told him, ‘Mr. Prime Minister, this is what needs to be done. I am convinced of it.’ As we spoke, Netanyahu brought more people into the discussion—Ron Dermer, Tzachi Hanegbi and then the military secretaries. And I realized that Netanyahu did not want to go through with it. I understood this not because he explicitly said so, but because he insisted that we needed to speak with the U.S. president and asked me to call National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan." Gallant made the call, with Dermer also on the line. "And right away, I heard opposition to the plan."

What was the nature of the opposition?

“He said that this would drag us into a regional war which was not the right course. Soon after, calls started coming in—also of Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin and others. I told the prime minister, ‘I am convinced we must do this.’"

This was clearly a way of inviting U.S. pressure, Prime Minister Netanyahu telling you to talk to Sullivan.

"I understood that from the very first second."

And what was the reason for the prime minister’s opposition?

"From day one, through the first weeks of the war—at least until the conclusion of the first hostage deal—the prime minister projected a deep sense of pessimism, which I did not share. Regarding the ground maneuver, he kept saying, ‘There will be thousands of casualties. Hamas will use the hostages as human shields, place them on rooftops and in doorways.’ And on this issue [war with Hezbollah], more than once he pointed out the window of his office at the Kirya and said, ‘Do you see all these buildings in Tel Aviv? They will be destroyed—nothing will remain—because of Hezbollah’s residual capabilities.’ In other words, ‘after we strike with all we have, they would bring everything crashing down on us.’ I strongly disagreed and told him that was not the case. I also urged him to convene the Cabinet as soon as possible."

After the initial consultations, and with no formal decision, Gallant returned to the Pit. Despite the uncertainty, preparations for what would have been the largest and most complex Israeli military operation since the Suez Canal crossing in the 1973 Yom Kippur War had to continue. As the Cabinet meeting approached, he tried to reach the prime minister by phone. According to his account, the Netanyahu was unreachable.

"We were only three and a half days past October 7. I sent representatives time and again to his office because I was trying to reach the prime minister by phone, but there was no response. This was a war, and I was the defense minister. I was calling from the Pit, I sent an envoy to his office, but he was not allowed in. Eventually, I returned to the prime minister’s office myself at the Kirya around 3:00 p.m. and found that I had arrived just as a coalition negotiation was concluding to bring Benny Gantz, Gadi Eisenkot and Gideon Sa’ar into the government. From that point on, they were considered part of the Cabinet."

The Cabinet convened in the Pit that evening. "Keep in mind, this was a meeting happening late in the day with a strict time limit. By the time I briefed the Cabinet, it was already clear that the prime minister, Gantz and Eisenkot were opposed to the operation. And I understood that the U.S. president had been brought in to pressure against it. I have no criticism of the Cabinet members—after all, they were being asked to decide within an hour whether to expand the war to another front without having had the chance to review the details, what we could have done in the morning (when Gallant had initially requested the meeting hours earlier), was not possible by the evening.”

Gallant describes the discussion as rushed. "During the meeting, I ordered the chief of staff to have the fighter jets take off, because if we didn’t move quickly, even if the decision was ultimately in favor, the opportunity could slip away."

But Gantz, Eisenkot, Dermer and Netanyahu all opposed the move. "And that was the end of it. The defense minister, the chief of staff, the head of the Shin Bet, the Mossad director, the deputy chief of staff, the Northern Command chief, the head of Military Intelligence and the Air Force commander—all supported the operation. In the end, the issue was rejected it, and the Cabinet votes against the decision."

I recall the argument of former IDF chief of staff Eisenkot—who was dominant in this discussion—that it would have been a severe strategic mistake, shifting the war’s focus to the north and preventing us from properly handling Hamas. And I have to say as a journalist, given the massive intelligence failure just three days before, it is entirely understandable that the political leadership lacked confidence in the military.

“What’s for certain is that everyone is entrenched in their positions, even to this day. Throughout the war, every time something happened in the north, I reminded them (those who objected): ‘We are paying the price for not making the right decisions at the right time.’ Whether it was the evacuation of northern residents, rocket fire on Manara, Metula or Misgav, the answer was always the same—that Hezbollah would have leveled Tel Aviv with its missile arsenal, that we would have been drawn into an unending war with Iran, etc. But here, history allowed us to ask a question we usually cannot: What if?"

Looking back, Gallant says that much of the IDF’s planned operation was ultimately carried out a year later. By the end of it, Hezbollah did not demonstrate "residual capabilities"—meaning it no longer had the power to reshape Tel Aviv’s skyline. In his view, the dire warnings had proven unfounded, and in hindsight, his position was correct.

At this stage, Gallant had been labeled by the Americans as reckless. From their perspective, he was the number-one risk factor for what they saw as a worst-case scenario: an uncontrolled regional war with Iranian involvement. Over time, they learned to work with him. The former defense minister recounts a phone call he received from his U.S. counterpart, Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin, following the assassination of Hamas leader Ismail Haniyeh in Tehran in late July 2024. This also came just hours after the IDF had killed Hezbollah’s chief of staff, Fuad Shukr—also known as "Sayyed Mohsen"—in Beirut.

By this point, Gallant was deeply involved in every aspect of the war. He was at Mossad headquarters with its chief David Barnea for the final discussions before Mossad’s operation in Tehran. From there, he was called back to the Kirya for approval of Hezbollah’s chief of staff’s assassination. He had not informed the Americans about either of these operations in advance—"naturally", he says.

"Shortly after Haniyeh was eliminated, I got a call from Austin. He asked me, ‘What are you doing?’ I told him, ‘Mr. Secretary, let me remind you that two days ago, twelve children were killed in Majdal Shams (from a Hezbollah rocket, n.e). I gave the IDF the order to take out Mohsen, and the window of opportunity opened. This man was a terrorist responsible for the murder of hundreds. And I told you—anyone who acts against us, we will strike. This is not a minor matter.’ Then he asked, ‘But what about Haniyeh? Why Haniyeh in Tehran?’

I told him, ‘He was Hamas’ Bin Laden. He knew everything, was directly involved in the planning, the slaughter of civilians, children, women, soldiers and the kidnappings. And this was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. You either take it, or you don’t. We decided to take it, and we stand by that decision. Anyone who fights us will be hit hard.’"

Gallant then reminded Austin: "These people—Haniyeh, for example—are responsible for an operation that didn’t just kill 1,200 Israeli civilians. There were also dozens of Americans among the dead and American hostages as well."

In many ways, this marked a turning point in the entire war. Until July 2024, Israel seemed bogged down in Gaza, unable to secure a deal and internally divided over the concessions being considered. There was deep hesitation about taking action in the north. But then, events began shifting rapidly in a way that reshaped the Middle East—leading to the collapse of the Syrian regime, a new political reality in Lebanon and the dismantling of the so-called "axis of resistance."

This shift was no accident. The IDF and the security establishment had been gradually escalating their confrontation with Hezbollah. The military Operations Directorate, led by Gen. Oded Basiuk, alongside the Air Force and Military Intelligence—determined to redeem itself after the October 7 failure—had been planning a series of calculated strikes. "Operations designed to ensure that Israel would win a full-scale war—without Nasrallah even realizing that such a war was already underway," as a senior security official put it to me.

Following the targeted killings of Mohsen and Haniyeh, Hezbollah planned a large-scale rocket attack in retaliation. But on August 25, the IDF preempted it with Operation This Is the Moment—a concentrated strike involving around 100 aircraft that targeted hundreds of rocket launchers and thousands of missile sites in Lebanon.

By this point, months of stalled negotiations over a Gaza hostage deal had passed. The security establishment had been pushing for the Biden-Netanyahu proposal (details to come later) to secure the hostages’ return before shifting the war’s focus northward. But the talks collapsed, and Netanyahu remained unconvinced about a military confrontation with Hezbollah. Gallant took his case to the Cabinet: "I requested that we shift the center of gravity northward and declare that returning northern residents to their homes was a formal war objective. My request was denied."

On September 17, Israel launched the pager operation—triggered by concerns that its secret may have been compromised. "There were a few incidents surrounding it," Gallant recalls. "We suspected that someone in Hezbollah had caught on to the pager scheme. We found a pretext and took him out. But then Hezbollah started conducting extensive inspections of their equipment. At that point, we had no choice but to act—this was a critical operation with enormous value. We had been preparing it for a decade, and the results were dramatic: over 2,000 Hezbollah operatives were wounded—fingers, eyes, legs lost."

“But the primary walkie-talkie operation, which were far greater in number and explosive power, took place the next day when the bulk of these devices were still in storage. That’s where they detonated. Again, these were separate operations. The only time all of this was meant to be executed as part of a single, cohesive strategy was in the plan for October 11."

"I was the one who carried the burden of the war and the offensive on my back throughout this entire war. Every major attack decision—those were my decisions. Except for one that wasn’t approved: Oct. 11. Everything else went to the PM or the Cabinet, depending on the issue, and was approved. These were all my initiatives."

Three days later, a window of opportunity emerged. ”The head of the IDF Operations Directorate entered my office and told me, ‘The chief of staff is on a flight, so I’m coming to you directly. We have the entire Radwan leadership in our sights, including Ibrahim Aqil. But we have no Cabinet decision on whether we’re even in a position to escalate against Hezbollah.’ I told him, ‘Prepare for execution as quickly as possible, and we’ll work to secure approval. As soon as the chief of staff lands, have him call me.’ The chief of staff lands, receives an update, and tells me that he supported the strike.”

A phone consultation was held with the prime minister, and the decision to act was made. "When that happened, on Friday afternoon, I realized that we needed to accelerate three operations we planned: first, the destruction of Hezbollah’s missile capabilities; second, the assassination of Nasrallah; and third, the ground maneuver in Lebanon. We had already reached a slope of escalation. Each of these assassinations was an isolated action—there was no overarching plan. And in fact—if I take a step back—from the beginning of the war through October 11, I was the only one consistently pushing to ramp up pressure on Hezbollah. We could not allow them to pin down our divisions, strike homes and force evacuations without paying a price. If they could do that for the cost of a single rocket per day, they could keep it up forever."

Gallant asked the Air Force to present him with the plan to eliminate Hezbollah’s leader. "I asked, ‘What are the chances of success?’ The answer was 90%. Then I asked, ‘How many tons of bombs are you using?’ They told me 40 tons. I said, ‘Double it. Make it 99% certain that we succeed.’ And in the end, they increased it to 80 tons."

10 View gallery

I asked, ‘How many tons of bombs are you using?’ They told me 40 tons. I said, ‘Double it': The scene of Hassan Nasrallah's assassination in Beirut

As preparations for the strike on Nasrallah were underway, Operation Northern Arrows—Israel’s official large-scale campaign in Lebanon—was launched. The Air Force carried out an unprecedented operation aimed at destroying the majority of Hezbollah’s launch capabilities and rocket stockpiles. "The results were astounding," Gallant said. "Out of 5,000 long-range missiles, they were left with only a few hundred."

Two days later, the Cabinet convened to discuss Nasrallah’s assassination. Gallant wanted the ministers to authorize the prime minister and defense minister to give the order when the operational window aligned. "It turned out that there was a majority of five to two in favor." Gallant called for a vote. But then, the same pattern from October 11 repeated itself.

"The prime minister requested a smaller consultation with the chief of staff and me. He paused the meeting. The chief of staff, Dermer and I stepped out with him. The head of Military Intelligence joined, maybe others. We went over everything again, reiterating our position. Military Intelligence explained, both in the full Cabinet and in the smaller forum, that there was a chance Nasrallah would flee his bunker—within a day or two, maybe even within two hours. It was hard to say. Then the prime minister returned to the room and said, ‘We are not making a decision. When I return on Sunday, we’ll discuss it again.’"

Return from where? From the United Nations. Netanyahu was scheduled to deliver a speech there. Summing up, Gallant says, "Essentially, Netanyahu left the country on Wednesday, with Nasrallah still in his bunker, no authorization granted, a majority in the Cabinet in favor of the strike, and Military Intelligence warning that Nasrallah could flee."

This is a major drama since “news broke the next morning about something I had been aware of but had not been involved in—and which, in my view, most ministers didn’t know about either: negotiations were underway between the prime minister and President Biden, conducted via Ron Dermer and Sullivan, for a cease-fire set to take effect the following morning. When this was reported, several ministers publicly said that they would not accept it. And then one of them even threatened to leave the government," says Gallant in a reference to Itamar Ben-Gvir.

Gallant refuses to speculate on why Netanyahu changed his mind. "Whether it was related to this threat or not, I don’t know," he says. "But on Thursday afternoon, we got a call from the prime minister. He said, ‘I just woke up, and I think you were right’—meaning the chief of staff and me—‘and we need to bring this to a decision as soon as possible.’"

A discussion was held, and the operation was approved. On Friday, Gallant met with the chief of staff and the Air Force commander to finalize Israel's most important strike during the war.

10 View gallery

Gallant with the IDF chief of staff and Air Force commander in the IDF headquarters Pit

(Photo: Defense Ministry)

"At 4:00 p.m., in the presence of the chief of staff and senior IDF officers, I called the prime minister in the U.S. and told him, ‘Mr. Prime Minister, based on the authorization given to us, my recommendation to you—pending your approval—is to carry this out tonight at 6:00 p.m. That’s the last possible window for the Air Force’s flight schedule, and if we delay into the night, we might lose the target. The Air Force, given that they are flying extremely heavy aircrafts, each carrying seven tons of bombs in tight formations, preferred to execute at this time for operational reasons. Six o’clock is the last possible moment. Additionally, we want to provide advance warning to the religiously observant public in Israel before Shabbat begins, in case of rocket fire. I am asking for your approval.’ The prime minister responded, ‘Approved. But I request to delay it until 6:30 p.m. because, at 6:00, I will be on the podium at the UN.’ We reviewed the operational constraints again and settled on 6:20 p.m. At that moment, I was in the Air Force command center with the chief of staff, the Air Force commander, and others. In seven seconds—if I’m not mistaken—84 one-ton bombs fell with precise accuracy, and Nasrallah was eliminated."

A recurring claim in parts of the Israeli media is that the security establishment was not aggressive enough during this war - and that you and Chief of Staff Halevi were personally responsible.

"I was the one who carried the burden of the war and the offensive on my back throughout this entire war. Every major attack decision—those were my decisions. Except for one that wasn’t approved: October 11. Everything else went to the prime minister or the Cabinet, depending on the issue, and was approved. These were all my initiatives, actions that either came from me or from below me in the chain of command."

<< Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: Google Play: https://bit.ly/4eJ37pE | Apple App Store: https://bit.ly/3ZL7iNv >>

Regarding the shift in the war, he says, "The moment we eliminated Aqil, the Radwan commanders and then their missile capabilities, we left Hezbollah without real operational strength. It was a gradual accumulation of the full plan that could have been executed on October 11. Unfortunately, we didn’t do it. Now, this wasn’t the complete plan because it also included the physical elimination of 15,000 Hezbollah fighters using their own walkie-talkies. I would put it this way: We climbed onto the highway using a goat path, when we should have been driving straight onto it on October 11. But once we got on, the ones pushing forward the entire time were the defense minister, the chief of staff and the security establishment—throughout the entire war."

Did Netanyahu want a cease-fire in the north without defeating Hezbollah?

"The facts are that throughout the campaign, the prime minister, Dermer and others approached me in Cabinet meetings, asking to deescalate in the north. You can see that there were negotiations for a cease-fire before Nasrallah’s assassination. The French, the Americans and about ten other countries welcomed it. That news broke in the morning. Then our own ministers came out against it. What does that tell you?"

Here's what you told me: the prime minister didn’t want to enter Gaza, didn’t want the October 11 strike, hesitated on Nasrallah’s assassination and only agreed after coalition turmoil. Why do you avoid summing it up as a direct statement about Netanyahu’s role in the war?

"Because I am not willing to make evaluative statements. I only describe the facts as they occurred in the places where I was and where I made decisions. I never said he didn’t want to act. I said that, particularly in October and November, there was a tone of pessimism."

I think some people will read this interview and wonder—what’s the deal with Yoav Gallant? Why won’t he speak his mind about Prime Minister Netanyahu, who fired him twice?

"Look, I don’t want to frame this in the wrong way. I came here to talk about the war and present the facts. This isn’t about personal squabbles. And I’ll tell you the opposite: to implement all these decisions, you need both the defense minister and the prime minister. And everything I brought forward—except for October 11—was approved."