They served in the Intelligence Corps and joined the Hostages and Missing Persons Headquarters at its inception or shortly afterward. In their roles there, they were tasked with one primary mission: to ensure the well-being of the hostages. For two years, they worked to understand the hostages' real-time condition, maintain the most up-to-date intelligence picture possible, help translate agreements into reality, and locate hostages who were still alive.

Now, for the first time in more than two years, they are meeting together: Maj. (res.) B., 26, head of the Hostage Status Department; Maj. D., 29, intelligence officer for negotiations; Maj. (res.) R., 33, commander of hostage release implementation coordination; Staff Sgt. (res.) A., 32, liaison to the families; and Maj. S., 28, head of the Targets Department. In a joint interview, they reveal what happened behind the scenes during the unit’s most intense, painful — and at times joyful — moments. It is a unit that has yet to complete its mission and has never shied away from responsibility

Establishment

When the war broke out, the Israel Defense Forces' Intelligence Corps’ special operations division was tasked with the mission of returning the hostages. The directorate, led by Maj. Gen. (res.) Nitzan Alon, initially worked to compile information on roughly 3,000 missing persons. As the picture became clearer, it focused on 251 civilians and soldiers who were abducted to Gaza on October 7, tracking their locations and conditions. The directorate’s operations were divided into two main tracks: operational and negotiation.

The operational track dealt with locating the hostages, assessing their condition and signs of life; planning ground maneuvers inside Gaza, including where the military could strike, how troops should move, and how such actions might affect the hostages or their captors. This included identifying terrorists who held exclusive information about hostages. The team also maintained direct contact with families, addressing their questions and requests, relaying updates, and navigating the constant tension between accuracy and immediacy, particularly in an era when families might first learn of developments through Telegram.

The negotiation track, led primarily by the directorate’s senior officials, focused on gathering intelligence to support negotiations, as well as analyzing the enemy’s understandings and strategic thinking. Both tracks worked in close coordination with the Mossad, Shin Bet, international mediators and forces on the ground.

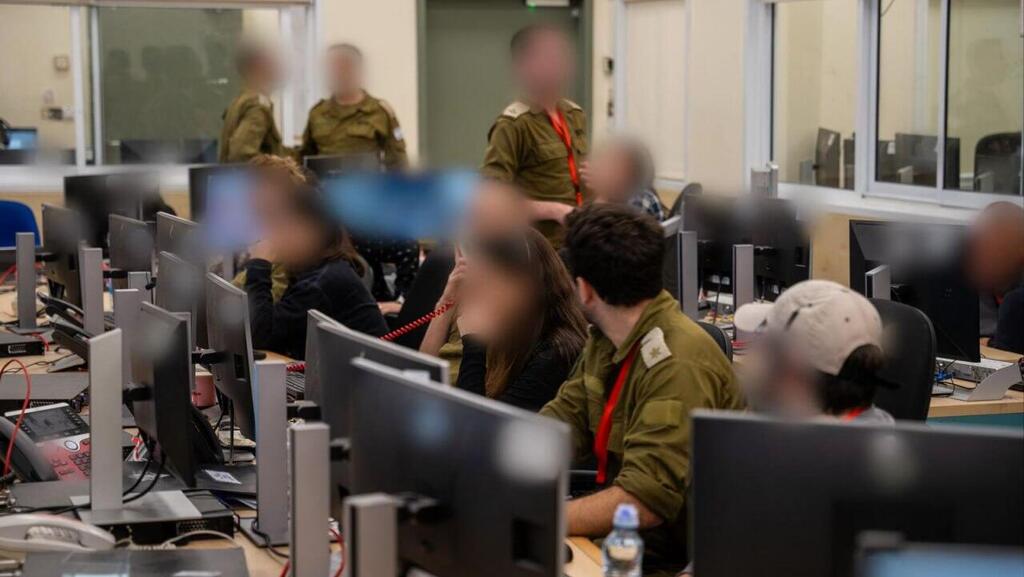

“The chaos people felt outside was not felt inside,” says B., who reported to the unit that Saturday at 9 a.m. She admits she initially believed only one person had been abducted to Gaza. When she arrived, she realized the situation was entirely different. “The first hours are critical for intelligence collection, and that’s where the need for a team like this came from. When I arrived, the team was already at work, trying to create order,” she says. “Intelligence was gathered from the field, from videos on social media, testimony from civilians and media reports. We adapted on the fly. Very quickly, we split into teams to bring order to the chaos, to understand how to deal with numbers like these of missing people, where they were and who they were.”

She describes the tense atmosphere between rooms: “People running in every direction, trying to understand as much as possible, but working. There was no sense of confusion.”

The soldiers assigned to the headquarters came from the Intelligence Corps, some in regular or career service, others called up for reserve duty. Over the past two years, new recruits assigned to serve in the unit have also joined. None of the personnel are residents of the Gaza border communities or have personal ties to the hostages, based on the understanding that staff are exposed to highly sensitive material and that a clear separation must be maintained between the personal and the professional.

“There was nothing more important or meaningful we could have done,” R. says of her decision to report for reserve duty at the headquarters. D. adds: “You wake up in the morning thinking about the hostages. You go to sleep thinking about the hostages. You commit yourself to a single goal.”

The hostages' personal information

The first two hostages to be released, Judith and Natalie Raanan, were Chicago residents with American citizenship. Over the course of the war, the importance of the foreign passports they held became apparent. “That was not a conversation at our level. Anyone who was abducted is Israeli, and everyone needs to be brought back,” B. stresses. “There was no piece of information about a hostage that intelligence personnel didn't know, even which apartments he or she had lived in over the course of their lives and who lived there,” R. adds.

Some information had to remain strictly confidential, such as the military service of certain hostages, including those who had previously served in sensitive roles. “That was information meant to be concealed. There are hostages whose military service has still not been disclosed,” says A. B. adds: “Much of the work was with the media, making sure nothing leaked, maintaining constant contact with the IDF Spokesperson’s Unit, military censors and reporters.”

The first deal: 'a Russian roulette'

The first deal, carried out between November 24 and December 1, led to the release of 80 women and children. “I remember a very deep fear that accompanied me throughout all the deals,” B. says. “Alongside the joy were complex feelings toward those who remained there, because we understood that the next deal was growing more distant. Our mission was to go to sleep with those who were still there, with the faces that stay with us when we close our eyes.”

From the families’ perspective, A. says, “it was Russian roulette. Until the last minute, they didn’t know who would be released. The hostage families are very united; you inform one family that it’s happening, and another asks what about us. Managing an operation like that is extremely complex.”

When the phases of hostage releases stopped, fighting resumed. “When we entered the first deal, it was clear to us that not everyone would get out. We had to prepare for the worst. We had a plan, and we stayed focused on those who remained there,” R. says. “There are no privilege and no time. Every day you prepare for two scenarios — a release happens or it blows up — and you live in a 50-50 world, ready for any outcome.”

The emotional roller coaster, felt clearly even during the conversation, was another central point for them. In the early days, R. says, psychologists and mental health officers moved through the headquarters, pulling people aside for one-on-one conversations. “We went through trauma from the exposure to the material, from the daily sense of responsibility for people’s lives. It was an indescribable weight. There were 18-year-old soldiers whose first assignment was at the headquarters. We had to keep our eyes open for one another.”

Meeting the first returnees

Information provided by the first hostages to return, during debriefings, shed light on the condition of those still held by Hamas. “Mia Regev provided significant testimony about the condition of Guy Illouz,” B. says, referring to the painful confirmation of his death in captivity, after the two were held side by side at Shifa Hospital. “The returnees told us who was left behind and how they were divided into groups. They also described who guarded them, through the identification of wanted individuals. It was internal intelligence that brought order. We were able to classify what had been unclear and begin drawing lines. When the first hostages came back, we could rebuild the headquarters to adapt to the reality.”

For example, hostages who returned from southern Gaza provided information about how they had been divided into compounds and groups. “The debriefers were intelligence officers with extensive experience, who approached the trauma with sensitivity,” B. says. “I was on the team responsible for drafting the questions and prioritizing them, with the most important being the list of names. There were hostages whose abduction we only verified after the first deal. The information that came in after that first deal arrived in many fragments, which we worked hard to process — even months later.”

One example of the uncertainty involved the fate of Dolev Yehud, whose body was found nine months after he had been classified as a hostage, inside Israel, at Kibbutz Nir Oz. “It took a very long time to prove that he was murdered and not abducted, and that he was located inside Israel,” R. says. “For a long time, he was defined as missing. As long as we had these ‘mysteries,’ and as long as someone was classified as being on our side of the border, teams did not stop searching in any sector.”

“We discovered that airstrikes we prevented did, in fact, prevent harm to hostages,” R. says, adding that the information they gathered also made a significant contribution to intelligence efforts for rescue operations. “The rescue of Louis Har and Fernando Marman in Operation Golden Hand in February 2024 was made possible in part by intelligence provided by women who had been held with them. Even small details that might sound insignificant, like what they saw from a window in the house or the medical condition of a captor’s child, helped us reach the terrorists who were holding them.”

Signs of life

Every sign of life that was received and passed on to families underwent a comprehensive review by intelligence officials, to ensure that the most reliable information possible was conveyed. At the same time, every detail extracted from footage helped collect and refine existing and new intelligence.

B. points to a video from November 2024 showing Daniella Gilboa, a surveillance soldier, documented inside a plastic bag to create the false impression that she had been killed in an Israeli airstrike. She was identified by her tattoos. “We had to determine whether it was true or not. Until then, many of those reports had turned out to be accurate. We were trying to understand whether Daniella had been killed, because there is a family on the other end that needs to know whether to sit shiva,” she says. “It was an intense week with a huge question mark hanging over it. In the end, based on an accumulation of indicators, we were able to say that, with high probability, she was alive.”

A. adds: “The notion of ‘probably alive’ is a qualified sign of life. It was an extremely complex situation. When intelligence officers walked into a family’s home and said that, we were overwhelmed.” R. refers to a video showing Guy Gilboa-Dalal and Evyatar David, filmed watching hostages being released during the second deal. “A deal is an opportunity, because Hamas brings hostages out,” she says. “We were waiting for any mistake that could help us. In that video, we examined the vehicle, tried to identify the driver and understand who the captors were. If you can track the vehicle and understand where it’s going, you can protect the area where they are. The mission is to locate, protect and bring them back — you look at an event like that as a tool.”

Deaths of hostages in captivity

Between the first and second deals, seven hostages were rescued alive in three separate operations. Thirty-five hostages were recovered dead, including 15 who were abducted alive, and three who were killed by IDF forces in accidental friendly fire.

“Come quickly, there are bodies that have been located in a tunnel,” A. recalls of the call she received on Saturday, August 31. “When they told me how many, I understood immediately,” she says, speaking through the pain as the officer responsible for hostages in the Rafah area, including the six who were murdered — Hersh Goldberg-Polin, Eden Yerushalmi, Ori Danino, Alex Lobanov, Almog Sarusi and Carmel Gat. “When you are holding their files — six young people with their entire lives ahead of them — all you can do is imagine them coming out alive.”

7 View gallery

From top left clockwise: Ori Danino, Eden Yerushalmi, Hersh Goldberg-Polin, Almog Sarusi, Carmel Gat, Alex Lobanov

(Photo: AP, Courtesy)

She immediately went to the headquarters to take part in briefing the intelligence officers who would deliver the hardest news of all to the families. “Every time I write to the officers responsible for family liaison, they are expecting an update about a sign of life. That day, one of them replied, ‘My God.’ They are used to seeing me function, but at that moment I broke down and cried. They brought everyone cups of water and then it was back to the mission; how to produce the most accurate intelligence picture for the families, with identification as reliable as a fingerprint. It was a long night that stretched into morning, ending with each officer knocking on the door of each family.

“To this day, it is a scar I will carry for the rest of my life,” she adds. “The truth was told to the families plainly and directly. Precise words, even the hardest ones.”

(Video: Courtesy)

Footage of the six hostages who were murdered in the tunnels lighting a Hanukkah candle

(Video: Courtesy)

B. also recalls the hardest moments, when the information had been verified at the headquarters but had not yet been delivered to the families. “I remember the hours between learning the news and the final identification, hours when you cannot speak,” she says. “I sat and looked at A., and there are no words that can ease it or add anything. Only presence. You sit in silence, and it slowly seeps in, the weight of it all. I debated whether to call in my soldier, who was responsible for that group of six. I wanted to protect him. But this is our reality, and it is a hard one. He is a soldier in the Hostages and Missing Persons Headquarters, and he will deal with it — across the entire spectrum. My responsibility, his responsibility and ours.”

About three months earlier, the IDF announced the deaths in captivity of Alex Dancyg, Yoram Metzger, Haim Perry, Yagev Buchshtab, Nadav Popplewell and Avraham Munder in Khan Younis. Initially, there was suspicion that, aside from Metzger, they had died from carbon monoxide inhalation following a fire caused by an Israeli Air Force strike. It later emerged that their captors had murdered them.

“We told the families what we knew at that moment with a high degree of confidence and waited for the investigation to provide the full picture,” the soldiers say. “In the case of the Khan Younis six, at the beginning we only had an assessment.”

“At the most basic level, every death of a hostage in captivity is our failure, whether the hostage was murdered by captors or killed by our own forces,” B. says. “We were responsible for their lives, and they lost their lives in captivity. That is a failure in our mission. It may be examined professionally, but on an emotional level it is very difficult to contain.”

“You cannot separate responsibility from blame. There is no need to sugarcoat reality,” S. adds. “You have to look failure in the eye, dig into it and understand how something like this does not happen again. I am comfortable saying that mistakes were not repeated. We learned from every incident, and that is hard. You have to understand where the blame lies and where a wrong turn was taken, and that same person often has to continue working in the unit. The decision is made by the commander, but the intelligence is on us. We even investigated events that almost happened. We didn’t wait for major disasters to learn. It was enough for a returning hostage to describe a strike that felt unusual and close — and we investigated it.”

'We realized Eli Sharabi didn't know the fate of his family'

Speaking about the second release deal in January 2025, D. says: “Every phase was like a Kinder Surprise. We waited for the list — who Hamas would decide to release under the agreement. That alone required preparing several possible courses of action. The second challenge stemmed from the lengthy implementation, which lasted 50 days, during which we had to ensure that every stage took place and that those that followed did as well, without anything going wrong along the way and causing the agreement to collapse. Every day carried the potential for a different land mine.”

That work, she says, included conveying messages to Hamas while also ensuring that the army didn't inadvertently violate the agreement. “Sometimes you also don’t know whether Hamas truly cannot release someone, or whether they are just claiming that. You have to assess it.” She recalls particularly difficult moments when the headquarters was forced to make decisions following violations of the agreement, such as the harrowing release of Arbel Yehoud amid a Gaza crowd, after the release of the surveillance soldiers rather than before them.

R. adds: “We prepared with a broad range of scenarios and responses, for example, whether a female soldier would be released or a civilian. The guiding principle above all was the hostages’ safety. There was always tension, because we did not want to do anything aggressive that could undermine the deal.”

R. recalls the moment she was watching Al Jazeera at the command post and saw Eli Sharabi, Ohad Ben Ami and Or Levy standing on their feet during Hamas’ cynical release ceremony. “We saw Eli Sharabi on the broadcast and realized that he didn't know the fate of his wife and daughters,” she says. “In real time, we passed the information to medical and psychological teams so they would be prepared for the fact that he would be emotional about reuniting with them and would then need to be told the devastating news that they were no longer alive. We had to coordinate across all tracks, update all the relevant authorities at the reception point, and also the representatives who were with the families at the hospitals.”

Arbel Yehoud and Gadi Mozes transferred to the Red Cross in crowds of Gazans

(Video: Reuters)

“The release of Arbel Yehoud and Gadi Mozes was disgraceful,” D. recalls, describing the moment the two were seen struggling with their remaining strength to make their way through the Gazan crowd that surrounded the Red Cross vehicles. “Emotionally, it was extremely complex, and operationally, you also have to be prepared for a possible extraction from within the crowd.” D. adds: “The second implementation phase of the deal was one of the most volatile events, the kind that could have caused the next phase not to happen. It created a great deal of friction between two sides that already had zero trust between them, and it required intensive negotiation efforts and mediation channels.”

As a result, she says, one of the lessons drawn from the Hamas-orchestrated ceremonies during that release was incorporated into the most recent agreement, which included a clause prohibiting such ceremonies.

When Gadi Mozes returned home, R. does not forget his first conversation with an Israeli official. “He was the oldest hostage to be released, and there was uncertainty about his medical condition. That first conversation with him is the one I remember most from all the deals. He was sharp, clear-headed, joked and asked, ‘So, can I sleep at home tonight?’ The officer speaking with him didn’t know how to respond and explained that he might need to stay in the hospital a bit longer. It was a moment of pure joy; here he was, back. What a man.”

D. also recalls the release of the four surveillance soldiers — Daniella, Naama, Liri and Karina — followed by the release of Agam Berger, who remained in captivity and was freed a week later. “I felt like these were my soldiers that I was bringing home, and that one of them would have to wait another week for her release. When Agam came back too, and I saw their reunion, there was a feeling that at least this part was complete. During the release phases I was focused, but only at home, when I got into bed, I saw the images of the returnees hugging their families and cried.”

When the last living hostage came home

As part of the most recent deal, 20 living hostages were released on October 13, 2025. In the days that followed, the bodies of the slain hostages were returned for burial in Israel, with the exception of Sgt. First Class Ran Gvili, whose body is still being held in captivity.

“There wasn’t a single person sitting in the operations room at that moment,” D. says, describing the first day of the deal. “Everyone was on their feet, like in the movies. Everyone was crying. That was something we hadn’t experienced in previous agreements, where we were happy someone came back but devastated that someone else was left behind. Personally, I felt a huge weight lift off my chest. But a minute after it was announced in the command post that ‘the living hostages have been received,’ we were already sitting down to the next mission — bringing back the fallen.”

R. recalls reporting that the final vehicle carrying hostages had crossed into Israeli territory, adding that five seconds later she was already issuing instructions to the Israel Prison Service to start the vehicles at the prisons, so they could move to fulfill the Israeli side of the agreement, the release of terrorists. “At the tactical level, it’s an overwhelming moment of excitement, but even then, you are always looking forward to the mission,” she says.

The headquarters, all of them emphasize, will complete its mission only with the return of the last hostage still held in Gaza and the full implementation of the agreement by Hamas. “Hamas’ part has not yet been completed,” D. says. “This is unfolding as stabilization of the Gaza Strip is already moving onto a track, but on the agreement track, the mediation of messages is still ongoing. Hamas needs to complete its part and return all the slain hostages.”

At the same time, they are already thinking about the day after the mission is completed. “After Ran returns, we will be the ones who turn off the lights in the unit,” A. says. D. adds: “In the military, most roles end with three dots — you pass the baton to someone else. When I finished my role, I realized I wasn’t passing the baton to anyone.

S. shares a painful personal story. “My eldest son was born just as Mia Regev was stepping out of the Red Cross vehicle,” she says. “He became the headquarters’ baby. At 11 months old, the morning after my husband returned from Lebanon, he passed away.” She says that for her and her husband, it was clear that once the shiva ended, they would take a deep breath and return to the mission. “We received full support from our family. That’s what made it possible.”

When her second son was born, the one she is now holding, his circumcision took place on the very day of the release under the most recent deal. Footage of the hostages’ release was broadcast on screens. Those who witnessed it said it felt almost symbolic, a reminder that the mission does not end when a shift is over but becomes intertwined with life itself — and that life, despite everything, goes on.